John Hurrell – 12 January, 2019

While reading this compendium of different pamphlet or broadsheet styles (with some inserted collages), I kept thinking of the second-hand magazine shops (like Ringo's) in Christchurch during the seventies that I used to explore, with their tatty stacks of all varieties of sorted reading material; the many magazines my grandmother used to buy and take to my uncle's farm; the fading gardening publications my dad acquired; my own curling copy of 'The First New Zealand Whole Earth Catalogue,' 1972

Auckland

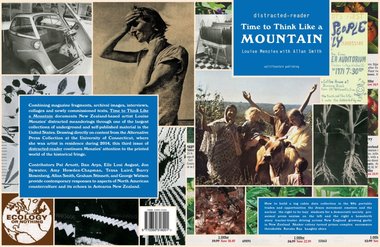

distracted-reader

Time to Think Like a Mountain

Showcasing Louise Menzies‘ research using the Alternative Press Collection of the University of Connecticut

Edited by Allan Smith and Louise Menzies

Contributors: Pat Arnott, Dan Arps, Elle Loui August, Jon Bywater, Amy Howden-Chapman, Tessa Laird, Barry Rosenberg, Allan Smith, Graham Stinnett, George Watson

Design: Narrow Gauge

128 pp, heavy paper, b/w and coloured images

Issue #3, Split / Fountain 2018

The wonderful name for this publication series seems to allude to Roland Barthes’ famous essay ‘Writing Reading’ in The Rustle of Language—overall about S/Z--that begins:

“Has it never happened, as you were reading a book, that you kept stopping as you read, not because you weren’t interested, but because you were: because of a flow of ideas, stimuli, associations? In a word, haven’t you ever happened to read while looking up from your book?”

While reading this compendium of different pamphlet and broadsheet styles (with some inserted collages, drawings and scribbled notes), I kept thinking of the second-hand magazine shops (like Ringo’s) in Christchurch during the seventies that I used to explore, with their tatty stacks of all varieties of sorted reading material; the many magazines my grandmother used to buy and take to my uncle’s farm; the fading gardening publications my dad acquired; my own curling copy of The First New Zealand Whole Earth Catalogue, 1972.

Examining the histories of ‘alternative’ pre-digital publications that promote an eco-conscious lifestyle that is healthy for individual, community and planet, this ‘hippie’ publication looks at some of Louise Menzies’ research while an artist in residence in Connecticut in 2014. Some of the related themes that interest her and Allan Smith are expanded in discussions by invited writing contributors or interviewees.

Menzies is well known as a passionate studier of printed matter (there is a plethora of samples here), and as her films show, is also very interested in various philosophical movements of the late thirties—to do with health and exercise. So this publication makes a lot of sense-especially as her personality (shown in early performances) has a strongly educative pedagogical streak. The interviews she presents here with Barry Rosenberg and Pat Arnott about prison life (and occasionally artworld social-protest work of the eighties) are immensely interesting.

Arnott is very informative about life in the Osborn Correctional Institute, particularly work in the vegetable garden and use of the library. Maps and outdoor photos are provided. The Institute was built on the site of a Shaker religious community in Enfield, and there is some historical (1865) descriptive material on that, plus a fabulous suite of eight symbolic ink drawings by Shaker artist Emily Babcock, made in 1843.

The theme of confinement and control, particularly of women by men, is explored in the text by Elle Loui August about the inspirational writing found in Jane Tolerton’s 60’s Chicks Hit the Nineties, and supplemented by reprints of some of Tolerton’s contributors, Rose Beauchamp and others.

There is also a characteristically witty article by Tessa Laird about the rights of animals-inspired by a 1985 page of Earth First discovered by Menzies—mixed in with discussions about Derrida and Taussig—and tying them in with the old joke ‘What is black and white and red all over?’

Dan Arps responds to two publication covers: one a pamphlet The Right to be Lazy by Paul Lafargue (possibly a precursor to Bertrand Russell’s In Praise of Idleness, 1935) published first in French in 1883, and then-as here—in English in 1969; the other, Lifestyle: A Magazine of Alternatives from 1972 (showing a family of American Hindus), butting the two together. The first he sees as an examination of the advantages the unemployed and poor enjoy in having plenty of leisure time, and the second, a facsimile look at cultures where individuals are seemingly less weighed under with social responsibilities-a false presentation of liberation.

Amy Howden-Chapman is interested in The Radioactive Times, a sardonic survey of nuclear calamities and protest that appeared in 1984. She describes the nuanced pink colouration of the document, using colour as a trope for the bodies of protesters and potential victims of leaking ponds, corroding walls and discarded radioactive rods.

Allan Smith’s essay, ‘An Affirmation that Won’t go Away,’ is excessively long and shapeless in its neverendingness. It might be argued Smith is doing his own version of Menzies’ strip of film or a print run on a looping printer’s conveyor belt, but he really needs a brutal editor to remove the irony from his title—to remove half of his ‘torrent’ at least.

Okay, Smith is the force that (with Layla Tweedie-Cullen) propels distracted-reader along, and maybe indulging him is part of the deal to get the project to come together, to summon the necessary organising energy that his collaborators benefit from. However, the first two issues don’t hint at untrammelled logorrhoea. Here we have sixteen pages of densely referenced text and ninety-two footnotes, not counting the six pages of accompanying ‘illustrations’.

I’m not saying that Smith is repetitive, dull or unreadable. He is never that. I’m saying simply that the essay lacks shape and overall direction. It meanders excessively, so much so that its many digressions become exhausting. Many will disagree I know. They will argue that his many reading ‘distractions’ are a plus, that they are his distinctive trademark.

Yesterday I stumbled across an excellent essay about the impact of digital technology by Roger Horrocks in the 2011 Enjoy publication Over Under and Around. In it he describes his own writing methodology as such:

I began writing this opinion piece in a notebook; and while I am now working on a computer, I will soon print out the text as hard copy to read and correct. I tend to be attracted more to a long text than a short one because I’m hopeful it will have more depth and complexity and demand slow reading. In many young people those preferences are fading. They prefer a variety of shorter texts, calling for surfing and multi-tasking skills. I’m well aware that digital natives may find the present essay too long and linear, with not enough images, links, or interactivity.

Smith’s essay is at least double the length of Horrocks’. I consider Smith’s distracted-reader piece to be a long, long, text, that aspires to provide slow, slow, reading. It is writing which in its scripted/sculptural materiality is about distraction that I would argue exists in a very different sense (it’s distracted-writer) from the mental reverie Barthes was getting at—which is pre-writing (though with him writing and reading often merge).

Smith’s dense, twisting, spiralling and zigzagging mega-essay is split into eight sections—separated by three centrally positioned asterisks. The sections can be drastically summarised as such:

1. The introduction points out that the publication allows Menzies to generate discussion about a multitude of ecological / environmental, labour /leisure focussed, ethical and community problems.

2. Smith kicks off the discussion by looking at Virginia Woolf’s 1924 essay about her traveling on a train with the fragile, withdrawn but perceptive Mrs Brown and the overbearing Mr Smith. Woolf critiques a certain kind of arrogant Edwardian masculinity and her ideas were re-examined in 1976 by Ursula Le Guin.

3. Le Guin wants to go backwards in time, to imagine the world before capitalism existed. Theoretician Isabelle Stengers helps Smith look at the 1999 Seattle WTO protests.

4. Stengers praises anti-capitalist activist groups that are not ‘normal’ or ‘stable’, but which are likely to be unsuccessful and disappear. With Philippe Pignarre she admires neopagan witchcraft for its adaptability and its useful rejection of codified doctrine.

5. Smith turns to Rebecca Solnit for her referencing of Woolf’s term ‘‘the history of the shadows”, connecting it to the Arab Spring movement.

6. He then looks at Eleanor Cooper’s description of Whina Cooper’s involvement with the famous Māori landrights hikoi, and then moves to discuss papakainga, ‘a meeting place to return to.’ Smith gives a house built by Tony Watkins in Glendowie as an example.

7. Smith reaches the surprising (to me) conclusion that Menzies’ research “is not seared by ardent conviction”, that it is “noninterventionist and nonprescriptive.”

8. Menzies‘ uncertainties bleed into Woolf’s anticipation of the demolition of the class order—as she ponders the ruminations of Mrs Brown—and the ‘creative destruction’ of the capitalist system.

I got interested in this particular publication because—when reading about its developments—I was exasperated by the conservative nature of the Democrat Party leadership’s resistance to Trump, and wondering about the radical left, if it exists in an efficacious form and if it can get a toehold—and how it might connect to the seventies, and printed matter then? I don’t think the publication really answers that question. Certainly (as we all know) the midterm US elections have since brought a change for the better, and we are now in the process of seeing if Pelosi and Schumer (and Warren, or Harris) can achieve something. And if Pelosi and the much younger (perhaps Sanders influenced) female Democrats can work together to build a new globally-sensitive North America.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.