John Hurrell – 6 June, 2019

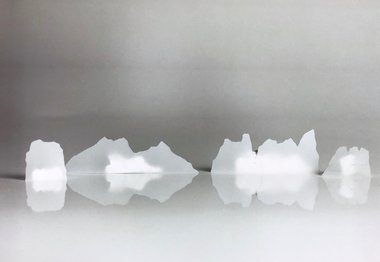

Whether overlapping cut-out ‘icebergs' (or rocky outcrops) hovering on a streaky grey field, blurry pink constructivist abstractions seen through a milky haze, scattered beads floating in mid air as if positioned by a fastidious juggler, or Belle Epoch accoutrements seemingly abandoned at the bottom of a murky aquarium, these photographs really get you scratching your head.

In this mini-survey of Esther Leigh photographs—a line-up that obviously doesn’t include her much earlier but brilliant enamel/graphite paintings—two recent series (Verge and Map) are juxtaposed with two older projects (Wade and Idle/Glade). At times romantic, mysterious, and seductive, while remaining exasperatingly baffling (in terms of technique) Leigh‘s images taunt the viewer by playing off blurriness versus acuity, barely glimpsed polystyrene masses versus textured or smooth planar surfaces. You ask yourself: to make these did she (amongst other things) manipulate focal lengths, use tanks filled with dry ice, introduce digital wizardry, or shoot the film through layers of thin transparent acetate or thicker translucent (and perhaps reflective) Perspex?

Whether overlapping cut-out ‘icebergs’ (or rocky outcrops) hovering on a streaky grey smmoth field, blurry pink constructivist abstractions seen through a milky haze, scattered beads floating in mid air as if positioned by a fastidious juggler, or La Belle Époque accoutrements seemingly abandoned at the bottom of a murky aquarium, these images really get you scratching your head. First of all they are beautiful, but they also tease, and continue to needle when you attempt to leave. You think, if I only linger a little longer and concentrate, I should be able to figure out how they were made.

Even though these (often faint) images are absurdly difficult to document, experienced directly Leigh‘s works are very rewarding—if you are persistent in your looking. And mini-retrospectives of her practice like this one are rare. Even the notion of sight and how its mechanics affect the viewing of objects suspended on a wall-which she is preoccupied with—is unusual subject matter in today’s politically obsessed times.

Some of these photographs, particularly those in the new Verge series (they are related to an earlier Verge series of 2010), have a restraint and tranquillity that is unnerving in its calmness—maybe even suggestive of places such as Zen dry (gravel) gardens like Ryōan-ji in Kyoto; internationally revered, constructed sites for meditation. Of course, there is a paradox because the technically puzzling elements (as thought processes) undermine the potential for meditation, imposing a distracting fixation on the image production as a challenge to be deciphered, and not (as seemingly would be desired) emptying it out, freeing it of excess ideational baggage.

The oldest, faintest and smallest works here, the pink and hazy Wade series, made in 2003, characteristically exploit faintness of definition, playing with strident circular, negative shapes and straight edged, channel-like layerings seen between rectangles. Leigh forces you to strain to understand what lies behind the outer surface—beyond immediate graspability. You know there is an image there, you can see traces and sense forms, but initially not much structure.

Leigh‘s enigmatic images, particularly the spacious grey Verge landscapes, also seem like a variety of Surrealism, like say that of the wonderful Yves Tanguy, but less busy. They are highly optical instead, while drawing on our very limited knowledge of translucency and reflection—and perception of space and cut-out edges.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.