Terrence Handscomb – 1 December, 2020

In her wonderful little book of six short essays, acclaimed essayist and novelist Zadie Smith writes: “Suffering has an absolute relation to the suffering individual—it cannot be easily mediated by a third term like ‘privilege'. If it could, then the CEO's daughter would never starve herself, nor the movie idol ever put a bullet in his own brain.” (Zadie Smith, ‘Suffering Like Mel Gibson,' in Intimations: Six Essays (London: Penguin Random House, 2020, p33).

EyeContact Essay #41

What a silly title. Of course we all know what happened at Mercy Pictures: two days before the exhibition People of Colour closed at the new Mercy Pictures gallery on Pitt Street, a bunch of artist millennials became infuriated by the show, and all hell broke loose when they complained to the press and it all went viral. The New Zealand art community was treated to displays of anger, vitriol, toxicity, side taking, offence taking, calls for apologies, refusals by supporters to distance themselves from the show and a most bizarre spate of white-confession neuroses from gallerists and others, that up until now, have been largely absent from New Zealand art.

The artists’ collective that is Mercy Pictures has for some time been detested by many young Auckland artists. This indignation has been further aggravated by the fact that Mercy Pictures has, up until now, attracted interest from serious patrons and this has riled the collective’s many adversaries. For those close to Mercy Pictures this is an old history, but ongoing resentments have continued to fester in the idea that the gallery was a happy little clique of white privilege; especially since it was widely believed that the parents of some of the collective members helped fund the venture. The fact that the principle members of the collective are of mixed ethnicity is overlooked because the issue here is identity and Mercy Pictures is simply too white. The People of Colour debacle was just waiting to happen.

Mercy Pictures is neither Artspace Aotearoa in its current incarnation, nor is (or was) it St. Paul’s Street Gallery in any incarnation. Mercy Pictures is quintessentially white. Their identity is white, their art, their values, their dress sense, their Instagram presence, their image that they communicate to the art world, all are enabled by what their many detractors identify as their white privilege, and this has offended a large swathe of the Auckland art community. The underlying idea is of course identity. Being cis, white and privileged is enough to be hurtful to those who are not cis and white and therefore not privileged. If you doubt this idea has traction, then checkout the InstaGram presence of Lourdes Vano @lourdes.vano (the young Pasifika Green Party candidate for Manurewa in the 2020 national elections) for clever vilifications of white privilege.

The principle argument against People of Colour goes something like this: placing the images of Nazi swastikas near to the image of a Māori flag, meant that Māori, Jewish, and other nonwhite peoples were hurt and offended by the referential seriousness of such cultural error. The horrendous evil that the Nazi swastika embodies, and continues to embody in neo-Nazi extremism, outweighs any argument for its legitimate use, such as critical irony or satire—es gibt keine legitime Verwendung des Nazi-Hakenkreuzes.

In cults of the individual, like those which pervade the art world, incendiary political upsets can quickly get personal and the explosive public reaction to People of Colour is no exception. But in a New Zealand arts climate where identity is valued above fact and an accusation is as good as a conviction, People of Colour provided the perfect battle ground for long simmering tribal belligerencies to explode.

In a rebuke to “Hoist that Rag,” EyeContact editor John Hurrell’s supportive review of People of Colour, a number of artists and writers called out Hurrell’s refusal to recognise the deep cultural and social offence that had been committed, and that he should disassociate himself from the show. Hurrell’s refusal to budge meant that he lacked proper empathy for the offended and this was met with further angry rebukes. A number of writers and artists demanded that their contributions to EyeContact be removed.

Commenting on Hurrell’s review, artist Sriwhana Spong tied the critic’s recalcitrance to not only his white privilege but also the general incapacity of privileged whites to see beyond the limits of their own biases. By ignoring the deep offence that People of Colour assailed upon Māori, semitic peoples, the LGBTQ+ community and other racial, social and gender identities, the supporters of People of Colour have failed to openly acknowledge the offence the show had generated. This is because the show’s supporters have instead chosen to focus on such dated and culturally blinkered ideas as artistic freedom and the rights of artists to say and do whatever they want in the name of free artistic expression. If the supporters of People of Colour properly understood the real issues surrounding race, gender and identity, then they would readily apologise to the offended, abandon their recalcitrance and decry the show.

As I see it, this sort of thinking has become extremely street savvy. It has learned how to weaponise guilt in ways that require very little intellectual finesse. A Kafkatrap, named after famed twentieth-century writer Franz Kafka, is a rhetorical device which induces a sense of guilt in an accused. It does so to the extent that any denial is deemed an admission of guilt.

When it comes to certain questions of race, power and privilege in a postcolonial setting, an accusation is usually all that is needed to diminish the power of the privileged. Such a Kafkatrap works something like this: Person 1, “All whites are racist. You are white therefore you are racist.” Person 2: “Yes I am white but I’m not racist. Some of my best friends are not white.” Person 1: “Only a racist would say that. Only racists deny their racism.”

Once trapped, an accused’s plea of innocence is an ineffective defence. Denial does not work in a Kafkatrap because it is invariably deemed an admission of guilt. The only way out of a Kafkatrap is to not step into one in the first place. In other words, stay out of social media and always stand just out of range. Do not commit to any standpoint that opposes the mob. Failure to do so will see the hounds of hell rising up to bite you, because therein lies the real power of cultural revanchism.

❦

Engaging with social media can be brutal. Especially when it is you who happens to be the one everyone else wants to troll. Social media has become a place where baiting and bullying are commonplace, and serious scholarly activities—such as Critical Race Theory, De-colonisation Theory, Queer Theory, Standpoint Epistemology, Grievance Studies, Trauma Narrative and so on—can be quickly reduced to a number of sharpened assaults in which a few dominant keywords, like “white privilege,” play a significant role.

So when People of Colour provided Mercy Pictures’ many adversaries with enough probable cause of a racial and cultural kind, they pounced. They were quickly joined by others with cultural and racial grievances of their own and things quickly escalated.

If it wasn’t for the degree of collateral violence, including serious death threats, police involvement and fake Instagram accounts, the ongoing episode of recrimination and resistance would seem comical. However, any attempt to laugh off the matter was widely deemed to be further proof of the sort of cultural privilege that affords such levity.

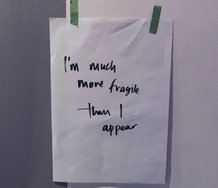

White privilege and racial othering are systemic forms of cultural and social violence. Identifying such privilege as a hybrid form of violence provides enough probable cause to inflict some serious payback. Let the privileged suffer as we have suffered under them. Let the kids at Mercy Pictures be punished and made to suffer. Their white privilege cannot protect them.

In her wonderful little book of six short essays written under strict COVID lockdown conditions, acclaimed essayist and novelist Zadie Smith writes: “Suffering has an absolute relation to the suffering individual—it cannot be easily mediated by a third term like ‘privilege’. If it could, then the CEO’s daughter would never starve herself, nor the movie idol ever put a bullet in his own brain.” (Zadie Smith, ‘Suffering Like Mel Gibson,’ in Intimations: Six Essays (London: Penguin Random House, 2020, p33).

Boy, have Mercy Pictures been made to suffer but does the punishment outweigh the crime? Something else is in play and it’s not entirely clear what.

There is more to all this than just resentment and the politics of grievance levelled against perfidious art brats who refuse to play along. There is an enormous body of scholarly literature which has been taught to university art students over the past decade, and this seems to have informed much of the rhetorical bellicosity levelled against Mercy Pictures and People of Colour.

The explosive reaction to the show saw Critical Race Theory and Social Justice Theory freed from their intellectual straitjackets in the academy and a brutal and extremely effective grievance machine mobilised in social media.

An excellent new volume written by cultural theorists Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay, Cynical Theories: How Universities Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody, was recently released by new independent publisher Swift Press (2020). In their book the authors note: “Critical Social Justice is neither a radical, new fight against social oppression nor a more sophisticated understanding of how society works. It is an unfalsifiable, ideological mess.” Or as American author and political pundit Mickey Kaus sarcastically quipped, this ideological “mess” is the “Great Awokening” of millennials.

In Anglo-American philosophy, unfalsifiable propositions are meaningless assertions because their falsity, and therefore their truth, cannot be effectively determined. When the perlocutionary force of accusation replaces the certainty of verifiable fact; when accusations of white privilege are fired off against cultural offenders like Mercy Pictures and anyone who supports People of Colour; and in a volatile, toxic social media environment where the court of public opinion is always in session, how can the charge of cultural error be defended? It cannot.

Sincere apology is the only atonement and this must be enacted in the public theatre of contrition in which all tokens of power and privilege are handed over. This ultimately serves nobody because the cultural tensions between sameness and otherness are maintained, they are not diminished.

As I view it, People of Colour marked a determinate action by a group of emerging Gen Z artists who were willing to question the peremptory imperatives and the earnest social justice themes that have lately gained enough power to dictate what sort of art is culturally legitimate. People of Colour, and the extraordinary reaction it provoked, demonstrated that social justice issues cannot be relativised in the service of bad semiotics and lazy thinking about how signs and symbols actually work. Many of those who have abandoned Mercy Pictures do not get this but have cowered instead to the threat of cancellation.

People of Colour asserted that identity politics are not absolute, they are relative and a lot of people hate that idea. One other point is glaringly obvious: when all hell broke loose, the semiotic significance of People of Colour became one big violent combat zone.

Postcolonial Theory and Critical Race Theory—of the sort that informed the language of Spong’s rebuke of Hurrell—entails philosophical themes that burgeoned in the midcentury writings of Emmanuel Lévinas (the face of the Other), Michel Foucault (systemic power and social violence) and Jacques Derrida (deconstructing sovereign discourse), to name the most recognisable. Postcolonial theorists and feminist critic Gayatri Spivak and Homi Bhabha also reached deeply into Deconstruction to lay down the intellectual ground of modern Postcolonial Theory. Their Postcolonial Theory had one simple efficacy: deconstruct the West. In the 1980s African American Harvard Law professor Derrick Bell refashioned Critical Law Theory and called it Critical Race Theory. Bell argued that United States law privileged whites over blacks.

All these theories constitute a significant body of serious scholarly activity, but the sort of Critical Race Theory that is taught to university art students in this country has effectively reduced the complex philosophies of mid-century white intellectuals and the non-white scholars that followed them, to a number of unfalsifiable assertions about othering and white privilege, to name a few.

When racism is combated by seeing it everywhere (cf Pluckrose and Lindsay, Ch. 5 “Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality: ending racism by seeing it everywhere”), this has serious implications for other art theories, such as semiotics. But binding the meaning of signs to racial and social hurt runs the risk of assigning to art a sort of flawed determinism from which ruthless forms of cognitive tribalism can easily emerge. The People of Colour fiasco has demonstrated that serious and legitimate conversations about the relationship between art, identity and meaning can quickly become one big tainted can of worms.

People of Colour was a whole bunch of signs. Whether intentionally or not, these signs and their gallery placement raised serious questions about how signs actually function. The fallout from the show demonstrated quite adequately what can happen when expectations about what art should say tears apart the symbolic fabric of everything that is recognisable. When signs become broken and their meaning is set adrift in a sea of mutability, then and only then will art become interesting.

Clearly, People of Colour caused offence to many people and the personal hurt that that entailed should be recognised. But the cancel culture hysteria that followed the show and the sudden invisibility of anyone who had previously supported Mercy Pictures, followed by a rash of atonements by those who did not escape the net, served only to enflame cultural differences, not placate them. No one, it seems, is in the mood to dispassionately consider what People of Colour might have actually achieved; nor to what extent the New Zealand art world is yielding to cultural imperatives that can only generate politically routine art with correspondingly short half-lives.

People of Colour has demonstrated how corruptible the semiotic relationship between reference and representation can become when art decries nuance. If we must live in a world in which determinate rules dictate how signs and images function, and that they must do so in ways that do not offend certain people—no matter how sincerely or how brutally those rules may be enforced in a public domain; no matter how extortionate and weaponised online cancel culture has grown; no matter how duplicitous the theatre of public atonement has become—then I will still go looking for art that fucks with preemptory expectations about what art must say and do. People of Colour has certainly done that.

Terrence Handscomb

Recent Comments

Terrence Handscomb

Open letter to Daniel Satele aka @sunny_biwl. Somewhat belatedly (your last post was 12 December) I’ve only just noticed that ...

Craig HILTON

this may be of interest (The Work of Art By Namwali Serpell) https://harpers.org/archive/2020/09/the-work-of-art-namwali-serpell/

JJ Harper

discourse...identity...sexuality...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 16 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 8:49 a.m. 4 December, 2020 #

I.

A Brief Summary of NZ/Aotearoa's Current Law Regarding Freedom of Speech

The right to freedom of speech is not explicitly protected by common law in New Zealand but is encompassed in a wide range of doctrines aimed at protecting free speech. An independent press, an effective judiciary, and a functioning democratic political system combine to ensure freedom of speech and of the press. In particular, freedom of expression is preserved in section 14 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 (BORA) which states that:

"Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, including the right to seek, receive, and impart information and opinions of any kind in any form".

This provision reflects the more detailed one in Article 19 of the ICCPR. The significance of this right and its importance to democracy has been emphasised by the New Zealand courts. It has been described as the primary right without which the rule of law cannot effectively operate.[16] The right is not only the cornerstone of democracy; it also guarantees the self-fulfillment of its members by advancing knowledge and revealing truth. As such, the right has been given a wide interpretation. The Court of Appeal has said that section 14 is "as wide as human thought and imagination". Freedom of expression embraces free speech, a free press, transmission and receipt of ideas and information, freedom of expression in art, and the right to silence. The right to freedom of expression also extends to the right to seek access to official records. This is provided for in the Official Information Act 1982.

Ralph Paine, 8:51 a.m. 4 December, 2020 #

II.

Limitations

There are limitations on this right, as with all other rights contained in BORA.

It would not be in society's interests to allow freedom of expression to become a license irresponsibly to ignore or discount other rights and freedoms.

Under article 19(3) ICCPR, freedom of expression can be limited in order to:

respect the rights and reputations of others; and

protect national security, public order, or public health and morals.

Jurisprudence under BORA closely follows these grounds. Freedom of expression is restricted only so far as is necessary to protect a countervailing right or interest. The Court of Appeal has held that the restriction on free speech must be proportionate to the objective sought to be achieved; the restriction must be rationally connected to the objective; and the restriction must impair the right to freedom to the least possible amount. The right to freedom of expression may also be limited by societal values which are not in BORA, such as the right to privacy and the right to reputation.

Hate speech is prohibited in New Zealand under the Human Rights Act 1993 under sections 61 and 131. These sections give effect to article 20 ICCPR. These sections and their predecessors have rarely been used. They require the consent of the Attorney-General to prosecute. Incitement to racial disharmony has been a criminal offence since the enactment of the Race Relations Act 1971. Complaints about racial disharmony often concern statements made publicly about Māori-Pākehā relations and immigration, and comments made by politicians or other public figures regarding minority communities.

Ralph Paine, 11:16 a.m. 4 December, 2020 #

I have posted the above comments simply as supplements to Mr Handscomb’s excellent essay, that is, only as further pedagogical aids.

We are experiencing a sustained and extremely dangerous attack on the notion of freedom of expression. In this regard, I believe that it’s crucial for artists (all of us!) to become students of NZ/Aotearoa's freedom of speech laws. Of course the discourse concerning these laws - and the laws of other nation states, etc. - is extensive. In my view the whole issue requires a rather sober approach.

As Walter Benjamin puts it in his essay on Kafka in Illuminations: "The gate to justice is learning."

Ralph Paine, 5:31 p.m. 5 December, 2020 #

To study the notion of freedom as defined by lawyers, state legislators, and judges is not to preclude a parallel study of how philosophers (in a generic sense) have thought freedom. Clearly, given the folding-unfolding-refolding regionality of all things, in our case this study will include teachings and terms as developed within both Maori and Pasifika conceptual worlds. Considering the latter, this study might begin by looking closely at Maori and Pasifika translations of the English word ‘freedom,’ and their usage.

In so called Western philosophy there are two main lines of thought on freedom, one major, one minor. The major line, and thus the one that sits best with state-thinkers, concerns itself with the notion of the will, freedom of the will, etc. and thus is all about representation, identity, and the determination game i.e. self-same subjects (I = I) determine their own actions by making free choices.

In marked contrast, the minor line regards freedom as an ongoing problem, a problematic as such: freedom-as-problematic. In this sense, although freedom manifests or actualises itself at every moment of life, it at the same time remains undiminished by these actualisations i.e. it exceeds its own materialised solutions. Hence: the minor line regards freedom as a pure positivity, a virtual, and thus insists on the necessity of liberating freedom from all determinations of the will, whereas the major line posits freedom negatively: the power of free will lies only in its competence to limit and mask the essential indeterminacy of all life, of all becomings.

In sum… The major line uses chance by trying to master it. The minor line affirms chance by letting go, by being carried: amor fati

Ramesh Nair, 5:26 p.m. 9 December, 2020 #

Re 'Nazi Swastika'

I didn't see the exhibition, but only photos of the offending icons.

I should point out that about 27-28% of Auckland's population has some Asian ethnicity, of which those of South Asian ethnicities are the second-most common, and of the South Asians, those of nominally Hindu religion are a majority. The term as used in this essay, 'Nazi swastika' is egregiously Eurocentric. In the photographs I see several swastika designs, and a 'Nazi Flag' -- a right-facing black swastika embedded in white roundel within a red rectangle. That is, a 'Nazi swastika' is a malapropism. The swastika, whether left or right facing, is found in early North Indian imagery, and also very ancient Iranian iconography. Later, around the 4th C BC to about the 4th C AD, both the left and right facing swastikas were used as symbols of the Buddha, during the first centuries of Buddhism when there were no depictions of the historical Buddha in human form. The swastika is still a revered Hindu symbol [ esp. amongst upper castes ], and for this reason it is probably best for White NZers to bin the term 'Nazi swastika' and use 'Nazi flag' as the accurate descriptor.

John Hurrell, 6:56 p.m. 9 December, 2020 #

Excellent comments, Ramesh. I guess most of us think the Nazi swastika has the L-shaped arms turning clockwise, and the Hindu /Buddhist one anti-clockwise. You are saying that distinction is hopelessly inaccurate.

Ramesh Nair, 7:56 a.m. 10 December, 2020 #

Hi John, it's almost certain that the artists behind this exhibition had no discernible knowledge of the development of iconographic symbols.

The Nazi flag is a combination of THREE elements : 1. the outer main red field, 2. The inner white circle. 3. The right facing swastika where the bent halves of the arms have about the same length.

The Red colour field symbolises the 'blood of the Aryan race'

The White symbolises the white skin of the European Aryan.

[ Aryan was a term largely used in the 19th/early 20th century to denote what are now called the speakers of Proto-Indo-European and early Indo-European and Indo-Iranian languages. A right-wing Hindu may even now use the term Aryan, but this is usually in reference to the early settlers of North India who brought the precursors of the Hindu religion into India.]

The red colour was also used European socialist movements from the late 19-th century onwards to denote 'the blood of the workers'. Therefore the red colour field was appropriated by two distinct totalitarian groups, the German National Socialists [ 'Nazis' ] and the Russian Bolshevik communists, as critical elements of their flags. Nowadays, this red colour field survives in this taxonomy only in the Chinese flag.

In Germany, where public displays of Nazi flags are banned, there's a history of altered flags trying to circumvent the law. I believe German police will classify any swastika, right or left, associated with a red or white background as illegal, along with a right swastika attached to any other national flag.

John Hurrell, 8:24 a.m. 10 December, 2020 #

Mercy Pictures did provide information on the sources of the flag images. In their catalogue. See the third link down at the bottom of my POC review.

Ralph Paine, 1:41 p.m. 10 December, 2020 #

Why do people insist on giving Mercy Pictures condescending little lessons about flags, symbols, and every other damn thing concerning art and life? Thing is, Jonny Prasad grew up in the South Auckland Hindu community.

Recently Jonny and I had a long conversation about swastikas. Turns out that as a young child he was often confused and somewhat conflicted about his community’s use of the symbol. He saw swastikas on all kinds of ceremonial occasions, and yet knew that in the world ‘out there’ the symbol was somehow evil. Subsequently, Jonny has carried out extensive research about this very singular and important symbol.

Ramesh Nair, 2:10 p.m. 10 December, 2020 #

Hi Ralph, if you are referring to my posts, I was responding to the reference in Mr Handscomb's essay on 'Nazi Swastikas'. I do not know Mr Prasad. The reason for my longish posts is that I was specifically directed here by someone prominent in the NZ fine art/museology field to this specific essay, who knew of my background.

I am half-Indian and half-Chinese. After graduating from U Otago, I spent about 5 months in the Dept of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum [ due to an interest in Central Asian Art.] I also spent 8 months at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, studying the origins and development of 19th century scientific racism in Europe -- hence my knowledge of swastikas, 'Aryan mythology' etc. Therefore I have the necessary knowledge to contextualise these matters, for anyone who might be interested.

Ramesh Nair, 4:20 p.m. 10 December, 2020 #

As an Asian-born NZer with a longstanding interest in the arts and literature, I can find no artistic merit whatsoever in this exhibition. Its naive over-interest in White Supremacist imagery, including that wretched green frog, makes something like 'Piss Christ' in comparison seem to have the sculptural aura of a Michelangelo Pieta.

Be that as it may, the furore over this show has shone a light onto some blind spots in the NZ civic discussion on race, representation, and ethnicity. The commentary around this show inadvertently reveals the very real anti-Asian bias in this country, particularly amongst those who identify as socially progressive.

The 2018 census reveals that 28% of Aucklanders at least partly identified as Asian, 15% PI, 11% Maori, 2% MELAA ( Middle East, African etc ). Of the Asian category, 36% are Chinese, 32% South Asian ( incl. Fijian Indian), 7% Filipino, 6% Korean.

Despite this, the article in 'Stuff', 'Auckland Gallery under fire for displaying Nazi symbols alongside Maori flags' by Josephine Franks seems to hail from an ethnic Cloud Cuckoo Land it its monomaniacal emphasis on the transgressions of juxtaposing White supremacist imagery in proximity to Maori flags. In Ms Franks' article, it is almost as if NZ has been ethnically cleansed of all its peoples apart from Anglo-White and Maori-- at least, no other ethnicities and sensibilities appear to be worthy of mention save the transgressions against Maori sensibilities.

The second reader comment under the 'Hoist that Rag' article does mention the NZ Jewish council, but the bulk of his commentary relates to disrespect against Maori, eg the reference to 'sacred banners'.

However, it is clear that the actual show showed flags from Apartheid-era South Africa ( would black, even white Africans in Auckland be thrilled?), ISIS ( surely no Auckland Muslim would approve ), along with Asian flags. The Korean flag is a combination of the yin-yang duality with I-Ching derived Chinese symbols. There is at least one Buddhist flag present utilising a swastika.

In other words, the vast amount of negative commentary about this show, presumably largely penned by Well-Meaning White People, has only served to 'otherise', ie marginalise, the 28% of Aucklanders such as myself who are Asian. The number of Asian Aucklanders is of the same magnitude as the sum total of Maori and Pasifika in Auckland.

So, why did the people who commented about the transgressions of this show so prominently complain about its offence to Maori, and ignore Asians? NZ is NOT a bicultural Maori-White nation; it is a westernised Asia-Pacific nation by dint of its demography and economic ties. If Well-Meaning White People in an Auckland with 28% Asian heritage have such a differential interest AGAINST Asian sensibilities, is this not a minatory version of 'White Privilege', one where Well-Meaning White People go out to bat for their 'preferred non-white ethnicity'?

JJ Harper, 2 p.m. 11 December, 2020 #

discourse...identity...sexuality...

Ralph Paine, 5:24 p.m. 10 December, 2020 #

FYI Jonny Prasad is one of the three artists comprising Mercy Pictures.

Yeah, I get it: you are yet another tiresome hater of the exhibition.

It just that you want to quibble over how BEST to hate it.

John Hurrell, 5:43 p.m. 10 December, 2020 #

Thanks for your comments, Ramesh. Unlike my friend Ralph I find them interesting. A POV we don't often hear. However I think the POC show can be interpreted as a sly attack on identity politics-- ALL identity politics--because of its holistic composition that blurs borders, and Power's essay. Terrence Handscomb's essay helps open up that unusual interpretation.

Craig HILTON, 4:33 p.m. 20 December, 2020 #

this may be of interest (The Work of Art

By Namwali Serpell)

https://harpers.org/archive/2020/09/the-work-of-art-namwali-serpell/

Terrence Handscomb, 11:55 a.m. 7 January, 2021 #

Open letter to Daniel Satele aka @sunny_biwl.

Somewhat belatedly (your last post was 12 December) I’ve only just noticed that on InstaGram you had been happily spewing up bile about People of Colour, Mercy Pictures and EyeContact. This also includes your response to my EC essay “What Went Down at Mercy Pictures.” What a noxious den of toxicity, doxing and name-calling your IG account has become. Someone should dob you in for violating IG’s hate speech policy. The irony is palpable, and would be comical if it wasn’t so virulent and destructive.

Everyone gets what you’re on about. It’s just that many of us don’t buy in to the way you are serving it up: your toxic listicles and the extortionary way you challenged anyone who hadn’t come out against PoC. Underneath it all, it is a theory of victimhood that enforces woke values and makes the idea of cultural reparation seem righteous, no matter how noxious that reparation may be. This idea has enabled the extraordinary conceit that your crusade is righteous. That sort of casuistry can be infectious and when mixed with the smell of blood and the principle of the chase, you have an incendiary ugliness just busting to get social media clicks.

But theory that focuses on victimhood runs against the sort of art principles that encourage disagreement, provocation and debate as a way of making sure art doesn’t collapse under the weight of repetition, novelty and boredom. Why do you think Elam is not on your anti-PoC listicle, whereas AUT is? Not everyone believes you.

I completely understand and accept your focus on grievance and respect for all identities. But the standpoint assumptions underlying your posts and those of your commenters are empty: the absurd idea that one cannot authentically speak out about issues that lie outside their own identity category – age, gender, race, class, trans, pan, whatever – is laughable.

So why is it that an ordinary Westie millennial of mixed ethnicity – and whom up until now New Zealand art hasn’t taken much notice of – has on InstaGram become a noisy, morally inflated, self-serving obsessive on a cultural crusade? By donning the mask of a righteous social justice warrior @sunny_biwl has discovered new-found power and a voice that people will listen to. Such is the potency of social media, and boy, you sure have been milking it.

I’ll answer to the Scheiße you served up in your IG response to my essay, but only if you first squat down and dump it all out again in this forum. That is, if the whole PoC fiasco still has teeth, and the idea that your BS should not go unanswered has not yet sunk in a sea of tedium.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.