John Hurrell – 29 January, 2021

Borell's selection and organisation seeks to provide thoughtful spectacle, and within the conspicuous architectural limitations of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki (and some Britomart sites) it surely succeeds. Painting and installations do particularly well, far more than sculpture or moving image. Many potentially powerful sculptural inclusions with greater physical and conceptual wallop simply would not have fitted into the space.

Auckland

112 indigenous artists from Aotearoa

Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art

Curated by Nigel Borell

4 December, 2020 - 9 May, 2021

I have always thought that the touring Dowse-initiated show of a few years ago—Māori Moving Image: An Open Archive, curated by Bridget Reweti and Melanie Oliver (covering 40 years)—has been the best contemporary Māori art survey so far, and maybe it still is. (It’s certainly the hippest.) Nevertheless Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art, LINK curated by Nigel Borell the then AAG curator of Māori art, makes you want to stop to catch your breath.

It is huge (the equivalent of 6 exhibitions with approximately 300 works), covers 70 years; and involves many types of visual art practice, not one. It is a very different sort of beast from the Dowse show: much more conservative in methodologies and content—more historic in its links, and ignoring any putative distinctions between art and craft—while emphasising technical diversity. Plus mischievously revealing the odd flash of internal community-directed provocation.

Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art is spread out almost entirely on three floors, the theatrical ground floor focussing on cosmology (the Māori creation narrative), the more staid mezzanine on the development of human society, and level one on women, health, community, and notions of beauty in manually crafted objects. Its organising structure is deliberately counter to traditional Eurocentric art historical paradigms, being focussed on Māori social and philosophical themes, not conventional production chronology.

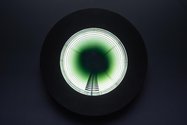

The show has a dramatic entrance, a set of three linked rooms that are in darkness to illustrate pre-being, a form of empty void. In them the neon and spot-lit works do well, but some dark paintings are also included to be seen in the half light. It can be argued that these works were not initially designed for such presentation, that prioritising such a dramatic and narrative-based installation over the conventional (perceived) materiality of well-lit paint is false. I guess Borell would answer you can look at them ‘normally’ in ‘proper’ light some other time, and that the artists are very happy with this unusual mode of display.

The exhibition is obviously pitched to as wide an audience as possible (especially Māori), aiming at introducing hitherto ‘obscure’ projects to more admirers, and surprising them. There is some cheeky and radically ‘unMāori’ work included from artists like Michael Parekowhai (with his huge elephant bookends). Curiously, that stringent adventurism on Borell’s part might have been showcased even more effectively had he also included conceptually bold contributors like PᾹNiA! and Wayne Youle.

Plus there are some sugary sentimental (‘touristic’) works that in my view weaken the project. The show would have been better focussed by not including these and a few other contributions that are too derivative of more original talent. This show is a mixed bag also in terms of visual styles and genres. Very few people will relate to all of the work—no matter what the content or style. That is to be expected.

Consequently, some pieces don’t draw me in on a personal level at all (I am either indifferent or annoyed) and others I find utterly enthralling. With these I am reluctant to leave the room I am so transfixed.

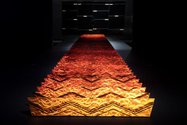

However Borell’s selection and organisation seeks to provide thoughtful spectacle, and within the conspicuous architectural limitations of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki (and some Britomart sites) it surely succeeds. Painting (via Emily Karaka) and installations (especially the Mata Aho Collective with Maureen Lander) do particularly well, far more than sculpture or moving image. Potentially powerful sculptural inclusions with greater physical and conceptual wallop by say Peter Robinson, Brett Graham or Robert Jahnke simply would not have fitted into the space, and might have upset the male / female balance anyway. Many of the contributors have within their diverse inclusions pieces that are surprising, works that often shatter preconceived popular notions about their practice.

There is a great deal of brilliant art to discover here if you pick through it carefully, often by names that are not that well known. Examples include: Ana Iti (Takoto, 2020), Hemi Macgregor (Agent Provocateur #4, 2012), Zena Elliott (Flow, 2017), Ngatai Taepa (He ata ki runga, he ata ki raro, 2020), Kereama Taepa (Pātaki Pakemana, 2017), Reweti Arapere (Poropiti Wairua, 2020), Israel Tangaroa Birch (Ara-i-te-uru, 2011), Saffronn Te Ratana / Hemi Macgregor / Ngatai Taepa (Tu te manu ora i te Rangi, 2008), Neke Moa (He mea? 2019), Buster Black (Black Painting; Night Landscape, 1962), Mere Harrison Lodge (Te-Toka-a-Tōrea, 1963), Colleen Waata Urlich (Ipu Tāniko, 2007), Jimmy Kouratoras (It’s Budget Bro, 2019), and Jeremy Leatinu’u (Queen Victoria, 2013). Fantastic work that is meticulously thought through and beautifully made.

There are also thrilling surprises from other artists who are already well known and highly regarded, like Shane Cotton (Te Puawai, 2020), Kura Te Waru Rewiri (Puhoro Meets the Stripes III, 2011), Lonnie Hutchinson (Aroha ki te Ora (Lover of Life), 2020), Maureen Lander (Wai o te Marama, 2004), Reuben Paterson (He Hue/Gourds: Kua tu te puehu, 2020), Shona Rapira Davies (There are No Bees in My Garden, 2020), Robert Jahnke (Whenua Kore, 2019), and Emily Karaka (CULTURAL ID; Marae, Maunga, Motu, 2020).

This complicated exhibition has plenty of informative bilingual labels available via either gallery walls, free brochures, gallery website or QR codes. Note that the small black concertina floorplan is key, especially if you match the numbered rooms in the diagrams with the sixteen labels presented online in various illustrated folders.

However while the show lacks a hardcopy check list of named works that would encourage repeated ‘seeking out’ visits—an inventory of titles that can be pondered for the sake of individual items (their own unique properties) and not thematic positioning by the curator—that infomation is available online. If you click on each artist’s name you can see their contributions, but not where they are located. You have to explore.

Toi Tū Toi Ora: Contemporary Māori Art is on till early May but remember, this year is rapidly skipping by. February is about to start and we might have more lockdowns round the corner. Explore this richly layered complex exhibition thoroughly now while you have the chance.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.