John Hurrell – 7 February, 2021

The most conspicuous questions that Apple's career presents include: the artist/subject's self (what is that anchored to, if anything: how is it constructed?); the artwork's location (who controls the conditions of display?); by implication, the artwork's elucidation (who guides the art historical interpretation?); the artwork's ownership (the means of acquisition, the attendant selection of viewers); and artist income (how to ensure it, even when the production ethos is bound to processes of dematerialisation).

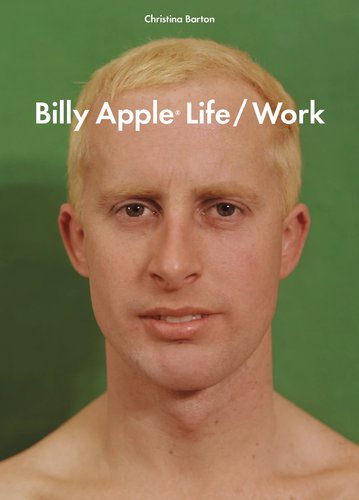

Christina Barton

Billy Apple® Life / Work

Text: Christina Barton

Design: Inhouse Design

390 pp, hardcover, b/w and coloured illustrations

Auckland University Press, 2020

With its clear elucidation, natty design and abundant photographs, Christina Barton‘s footnote-rich 400 page book on Billy Apple is a dazzling contribution to New Zealand Aotearoa’s and international art history—a joy for anyone intrigued by Apple’s projects or who is fascinated in general by ‘post-object’, ‘idea’ or ‘conceptual’ art.

Her hefty authorised biography is divided into a series of six chapters (each divided into sequences of carefully positioned blocks of narrative) that chronologically look at aspects of Apple’s evolving identity, changing geographic location, constant preoccupations, and artistic influence. These are approximately bookended between discussions (in the prologue and epilogue) of Barton’s working process and use of Apple’s considerable archive.

Barton’s scrupulous research (nudged on by her friendship with the artist) gradually unfolds the story of how Barrie Bates (b. 1935)—a socially dysfunctional Epsom schoolboy—grew to became an international avant-gardist with a name that presented himself as a living (and eventually registered and trademarked) artwork. Initially a Pop artist in London (he went there on a study scholarship in 1959) and (after a period at the Royal College of Art) a designer and conceptualiser for various marketing firms and founder of an innovative experiemntal gallery in NYC. After two lengthy tours in New Zealand, he returned here to live and work permanently in 1990.

This biography has an excellent section on Apple‘s more recent interest in cells from his body being used for medical research and their continuing to reproduce long after his death, as well as a thorough look at the commercial and legal implications of the Billy Apple® brand, the marketing possibilities with assorted products. It also explores his many friendships with, influence on, and mentoring of much younger artists and artist collectives. Very useful also are its comprehensive bibliographies for online and hardcopy Apple articles, and an index for mentioned artworks.

Barton crams a lot of fascinating projects in, chosen from Apple’s huge ‘smorgasbord’ of archived possibilities—unexpected surprises from one decade alone include: Herbert Distel’s The Museum of Drawers cabinet (1970-77) where Apple emptied and cleaned the fifteenth drawer; zigzagging Laser Beams (1970) between the columns of his NYC gallery APPLE; design projects in NYC (1967-68); Neon Floor #3, 1969 where gathered neon tubes hang from high up a column; Searchlight Piece, 1969, with the artist standing in its glare.

My favourite projects from Apple’s complicated and varied career are the art transactions of the eighties that involve the skeletal setting out of exchange procedures such as selling, bartering, commissioning, auctioning, gifting, collector acquiring, print numbering and signing, IOUs, half price reductions, published pages, a painting made for not selling (only lending), and the paying of the artist’s bills. I greatly enjoy the intricate commentaries on these radically no-nonsense (but aesthetically beautiful) ‘documents’ by Barton in this book, and elsewhere in others, by Wystan Curnow, Greg Burke, Anthony Byrt, Tony Green and Michelle Menzies. He has many articulate admirers, and with this topic, Apple’s documentation of his inventive interaction with the market as art subject-matter, is an extraordinarily rich area to explore.

I’m also particularly fond of the Subtraction works of the seventies. Not only is there an obvious connection with traditional sculptural practices like those of Michelangelo or Rodin (their elevated activities carving marble now amusingly connected to the menial task of cleaning) but a quote from Apple like ‘If you wipe a dirty spot off a wall you’ve removed it, but you haven’t eliminated it. You’re stuck with a dirty rag you didn’t have before‘ is linked to his later art transactions, especially with fiscal exchanges. Like dirt removed from a wall and added to a cloth through rubbing, money that is payment for art is subtracted from a buyer’s account and added to the seller’s. I’m fascinated by the parallels.

The design for this book is eye-catching—one marvels at its use of tiny orange footnote numbers—but I wonder if its modest size is a lost opportunity. There are many small photographs that deny the reader fascinating detail unless they happen to have a good magnifying glass. I think that there is an urgent need to publish a large format coffee-table book on Apple’s practice because it is sensual as well as ideational. As an ad guy as well as avant-gardist, Apple has never been visually dry. He never underplays the optical materiality of his art projects, or the gallery goer’s spatial experience. In The Given as an Art-Political Statement series the visitor’s bodily encounter with each gallery’s architecture and censured elements was significant. A big book (like say Peter Simpson’s biographical volumes on McCahon) would have exploited the photographic documentation, drawings and floorplans of Apple’s archive to the full. And thumped home with large images his diagrammatic use of diverse materials ranging from shiny brass pins to glowing etched Perspex.

Barton’s solid hardcover book has a very different feel and organisational structure from that of the other major (comparatively recent) Apple publication, Wystan Curnow’s Sold on Apple softback, for it is not an anthology of articles (nor record of writer/artist collaborative strategies). It attempts to provide a cohesive overview of Apple’s career and preoccupations, using colour images and working drawings, and making cross referencing links between different periods of the artist’s career. And thick though the volume is, because Apple is a workaholic, it could (like Simpson with McCahon) be even bigger, and split into two large thick books.

Note though that a few inaccuracies slip through that seem to originate from Apple’s archives rather than from Barton herself. For example, with Untitled Subtraction (1975), the book states the door of the Print Room of Canterbury Society of Arts was left partially open so it was only a crack to be looked through—but not entered (1). Actually it was fully enterable. You could walk around inside the space and enjoy the controlled light; my memory (for it was the first Apple work I personally experienced) is confirmed by John Summers’ facetious review in The Christchurch Star, quoted in Curnow’s book (2).

Another example is the omission in the main text of Waikato Museum / Te Whare Taonga o Waikato’s spectacular iteration of Severe Tropical Storm 9301 Irma in 2002, an important precursor to the smaller iterations at Window and Te Tuhi three and four years later (3). Barton brackets all the iterations as within 1998-2005 (in fact it was 1998-2006), starting with Hamish McKay, but the ignored Hamilton show (which I was involved with, but not the initiating curator) was presented in the largest art space—in terms of floor area—in the North Island and so had substantial impact. These gripes are minor and certainly not typical, but I’m following in Apple’s footsteps of stringent censuring in mentioning them.

Make no mistake, this is a great book. The importance of Barton’s study of this immensely unusual, pioneering international artist lies in—outside of its biographical particulars—its highlighting of certain questions that are reflexive in nature; art scrutinising its own processes. The most conspicuous ones that Apple’s (often collaboration assisted) career presents include: the artist/subject’s self (what is that anchored to, if anything: how is it constructed?); the artwork’s location (who controls the conditions of display?); by implication, the artwork’s elucidation (who guides the art historical interpretation?); the artwork’s ownership (the means of acquisition, the attendant selection of viewers); and artist income (how to ensure it, even when the production ethos is bound to processes of dematerialisation). It is a densely packed—but by necessity selective—highly informative account; absolutely essential for anyone interested in this country’s cutting edge contemporary art.

John Hurrell

(1) Christina Barton, Billy Apple® Life/Work, Auckland University Press, 2020, p.197.

(2) Wystan Curnow, Sold on Apple: The Complete Wystan Curnow Writings, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, 2015, p.25.

(3) Barton, ibid, p.326-329.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.