John Hurrell – 21 November, 2022

McAvoy believes these circles (and all their community trappings) tell us much about the human mind and art, and I believe he is right, but for different reasons. I care about whether they might be called ‘art' (it can't be assumed), who is saying so, and who deems the social and historical impact of that decision worthy of study. And I note that the discussion is embedded in an academic art matrix that is driven by research, and am not entirely convinced that should be the case.

Emil McAvoy

Soft Launch: An Exopoetics of the Crop Circle Phenomenon

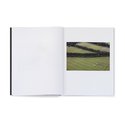

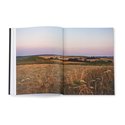

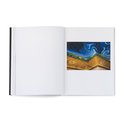

Coloured photographs by Emil McAvoy

Essay by Chelsea Nichols

Design by Emil McAvoy with Michael Mahne Lamb, Greg Simpson and Harry Culy

51 pp

PUFF PIECE x Bad News Books 2022

Famous for sporadically appearing suddenly overnight in the wheatfields of SW England and other parts of the world, the bafflingly intricate crop circles raise questions about prankster hoaxes, unusual natural occurrences like spiralling wind currents, or supernatural or extra-terrestrial phenomenon.

Whatever their cause, the question arises—what has this debate got to do with art? Why would a Kiwi artist like Emil McAvoy be so interested that he would go to Wiltshire county (known also for its chalk horses, Avebury henge and Stonehenge) to photograph the circles and aspects of their landscape and examine their social environs (and commercial add-ons) in person? To then make an exhibition and book. Why would he bother?

The cause of the circles—their origins—is an obvious and controversial point of interest. Is sitting on the fence about the likelihood of hoaxers (as McAvoy does—he doesn’t consider it a problem) a viable option? Is hesitating to state it even as an issue a responsible position? Or is it, by not taking a side, a soft option—indeed it may be a soft launch?

In her catalogue essay, Emil McAvoy:The Art of the Crop Circle, Dowse curator Chelsea Nichols writes of such a launch as McAvoy’s term for crop circles acting as “test sites for extra-terrestrial communication,” locations designed to attract human groups such as the Centre of the Study of Extraterrestrial Intelligence (CSETI) that are keen to communicate. The show’s title usually however applies to an understated announcement free of razzamatazz. A controlled dispersal of information that emphasises the tentative. Like McAvoy’s low keyed promotion of his exhibition and book at PHOTO OP.

Outside of that book launch, you could argue that the title is actually a subtextual (not openly declared) sneer at taking what is perceived as the socially easy road—a dismissive term aimed by the essayist at those she believes are being too dismissive. For instance: ‘but for sceptics and extremely boring people, the explanation is much simpler: all crop circles are merely made hoaxes’; or begging the question: ‘Surely, those who dismiss all crop circles as mere hoaxes have missed the point. After all, whether you believe in their alleged paranormal or supernatural aspects, crop circles represent important sites of pilgrimage for those asking the most perplexing questions about our place in the universe…’ However it is simply not true that smart-alec pranksters always create “important sites of pilgrimage.” They might. Those qualities would have to be argued as per fits the case, as also whether kneejerk sceptics would always be ‘boring.’

In the end Nichols believes McAvoy’s investigation is telling us something about the nature of art and the human mind. Something about the art viewers instead of the wider world of experienced phenomena, a position that might itself be seen as a politically easy soft option.

That is fair enough if you think hoaxers can make art: even if it is a subcategory of ‘inauthentic’ art that includes works by forgers like Karl Feoder Sim (Goldie) and Han van Meegeren, ‘high art’ conceptual artists like Elaine Sturtevant and Sherrie Levine, or drawing virtuosos making fake ‘money’ like James Boggs. But it is not possible if you seriously think aliens can make art, because art by definition is always human made. It is an anthropological phenomenon.

Of course this is complicated further wheh curators sometimes take on the role of artists, and use the Duchampian tradition of the readymade to choose manufactured items found in shops, to make them art. To make by choosing. As is normal now, they might also pick items found in social history museums. They might also select objects found in the natural world, discovered in natural history museums.

One example I’ve seen was in part of the 2000 La Beauté Biennale at Avignon, when fashion guru Christian Lacroix was director. There a selection of objects from the natural world was exhibited in an art context to be seen as beautiful. These included botanical watercolours of plants, plants themselves, actual crystals, insect specimens, crabs, rock formations, pieces of seaweed, and driftwood.

In a sense Nichols and McAvoy are half correct, if you, say, take the position that the terms ‘supernatural’ or ‘extraterrestrial’ are nonsensical, that all possibilities are natural (only some are unexplained), and if on the planet earth, terrestrial. These options would be art if nominated as such by a (non-alien) curator acting as an artist surrogate. What I’m saying is that the nominating powers of a thoughtful artist or curator cannot be open-ended; these claims cannot be proposed by any type of intelligence. Any nonhuman variety.

McAvoy believes these circles (and all their community trappings) tell us much about the human mind and art, and I believe he is partially right, but for different reasons. I care about whether they might be called ‘art’ (it can’t be assumed), who is saying so, and who deems the social and historical impact of that decision worthy of study. And I note that the discussion is embedded in an academic art matrix that is driven by research, and am not entirely convinced that should be the cause. Only a little—for reasons I’ve already given.

For McAvoy the interest is there anyway, irrespective of anthropological classification or rigor. On the other hand I’m seemingly examining pin heads for the counting of angels, shaking a tree from which few apples will fall. The circles’ existence however creates much community enthusiasm, income, and speculative mental attention. All worthy things McAvoy and Soft Launch help to perpetuate.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.