Peter Ireland – 11 August, 2010

Despite the impressive content of these two shows, each of them on their own and in their lack of togetherness represents a huge failure of perception and nerve in 2010. We congratulate ourselves on becoming a Pacific culture, but if the idea's to have more legs than the clean green New Zealand mantra, museum culture needs to stop resting on the rather dry laurels of the Eurocentric Modernist assumptions underpinning exhibitions of this kind.

Wellington

John Pule

29 May - 12 September 2010

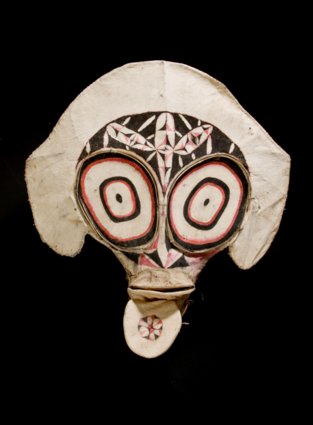

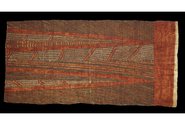

Paperskin: the art of tapa

19 June - 12 September 2010

The conjunction of Wellington City Gallery’s John Pule mid-career survey with Te Papa’s historical tapa exhibition couldn’t have been a happier or more instructive accident. Neither show is sprawling: Pule’s contains 26 works and the tapa about 40, offering comprehension without risking exhaustion, each informing the other in ways their curators could not have envisioned. It would’ve been fun to mix them up.

On the face of it, the Pule show has been constructed to show where he’s come from and where he’s at. Paperskin exists to redeem the tradition of tapa from the clutches of the ethnologists, updating - but only slightly - the impulse that lead early Modernists to admire “tribal art”. Whatever creative energies exist in all these works that the two shows celebrate - and it seems considerable - it’s paralleled by the strategies of (still largely Pakeha-flavoured) exhibition venues to foreground such material productions, an institutional positioning saying as much about contemporary museum culture as it does about the objects themselves.

Since the phenomenon of Te Maori in the mid-1980s, it seemed as if Maori and Pacific cultural material had emerged from the long shadow of being considered merely ethnic curiosities. So, what to call it now? Well, we called it art. That apparently simple transition, and implied upgrade, had its own set of hooks that these new shows seem blissfully unaware of. The walls and ceilings at City Gallery and in Te Papa that the objects are sited within are the physical equivalents of the rigid assumptions conceptually underpinning these two exhibitions.

Of course, it’s great to see the stuff. The tapa show was organised jointly by the Queensland Museum, the Queensland Art Gallery and Te Papa using material from their collections, and is the first Pacific show to be held in Te Papa’s major temporary exhibition space since the museum opened in 1998, so these opportunities don’t come often. (A bit odd really, as one of the earliest plans for the museum project was inscribed “Pacific Arts Centre”. Paperskin follows a show about Pompeii.) And John Pule’s work, while known widely through reproduction, has rarely been seen in quantity south of Auckland where he mostly exhibits., and the City Gallery show is the first attempt to survey what he’s been doing.

Seeing the stuff is one thing, but what we make of it is another, hugely conditioned by, firstly, the curatorial approach and, secondly, the exhibition design. In both cases it’s standard late-Modern, Eurocentric museum practice. It’s over a quarter of a century now since Te Maori, and on current evidence that seemingly landmark exhibition was either a blip on the screen or the lesson it might’ve given is taking an awfully long time to register. In the Paperskin show the objects may be “beautifully displayed” but they remain as stranded from their cultural origins as anything in a cluttered ethnological display a century ago - the sort of thing museum studies students are taught to jeer at. At the City Gallery Pule’s work is shoe-horned into two spaces and three categories that run counter to the stream of his production and knot up the richly diverse skein of its origins. Museum professionals seem able to upgrade their buildings and update their technologies, but their conceptual framework remains as cobwebby as Miss Haversham’s parlour.

The trophy show - artworks lined up like stags’ heads in a baronial castle - is the easy option. Despite all the promises of something other when the institution was being planned, Te Papa’s long-running Toi Te Papa/Art of the Nation (now into its fifth year) is a good but shameful example. Going through such shows is like working your way through a packet of biscuits when you’d prefer to be making a factory visit. The sources of art and the making of it is a messy business, and however intriguing and illuminating (as if that mattered!) it’s all tidied away in the interests of some anal notion of professionalism. Just how Pakeha is that, guys?

The weekend Paperskin opened there was at Te Papa - whether by accident or design, it was tucked safely away on another level - a kind of tattoo-fest, held in a large area usually hired out for conferences, displays, whatever, where a diverse range of Livingskin operators - from respected moko artists to the parlour practitioners serving self-imagined outlaws - worked on the bodies of those eager to be marked for as many reasons as there are stars in the Milky Way. The atmosphere was slightly chaotic and mildly scary. The whole space was visually messy. And being in the presence of so much concentration and endured pain certainly sharpened one’s own awareness. In a nutshell, it was thrilling. In every respect there couldn’t have been a greater contrast with the conditions prevailing in the Paperskin exhibition up stairs. While it’s a slippery slope to talk numbers - but that is an important consideration at Te Papa - the tattoo thingy was thronged and Paperskin wasn’t. Ultimately, though, it wasn’t a question of numbers, it was a question of the difference between the living and the dead. At Te Papa that day it was a blindingly clear distinction, and one that 21st century curators in Aotearoa/New Zealand need to get a grip on if museum culture is to have any future.

John Pule, mercifully, is a living artist - of images and words - and according to the label information he regards himself primarily as a poet. And why shouldn’t he, coming from a tradition where the notion of a distinction is foreign? McCahon may have tried to reunite images and words but clearly failed, because in the Pule show the words have been corralled off in their own space as if Eurocentric categories meant more than the chronology of the artist’s work. A further Eurocentric assumption still with us is that large paintings are “more important” than smaller prints, an assumption plainly illustrated in the exhibition’s structure. Again, the prints being the result of a collaboration - with Marian Maguire - may have rendered them “less authentic” in terms of Eurocentric ideas about artistic authorship - notions running counter to just about everything in the Paperskin show, for instance. In terms of the artist’s work and our comprehension of it, mixing the two strands together would have been more illuminating, as well as giving the installation some much-needed light and shade: the cramming of 13 large works into the smaller gallery doesn’t do anyone or anything any favours. Obesity is seldom pretty.

All origins aside, maybe Pule’s really just another artist producing work that fits neatly into this late Modernist exhibition culture? Maybe all the Pacific stuff is just window-dressing and marketing strategy? The cynic could easily observe that the artist came to New Zealand at the age of two, and apart from a couple of brief visits to Niue has always lived in Auckland. This may be difficult terrain for a show to address, but there’s no hint within it whatever that such questions might exist let alone be discussed. It’s not a question of authenticity (a Modernist preoccupation anyway) but simply part of the rich cultural mix.

The City Gallery is at pains to position Pule as an innovative Modernist artist. The basic structure of the exhibition is predicated on a division between the more haipo-influenced work after 1991 when he first visited Niue and the work after 2000 that appears to be less influenced by the tradition. He’s “moved on”, and in so doing pays useful tribute to the Modernist notion of progress. Some of the labelling is more instructive than perhaps intended: Pule pushes the formal, thematic and conceptual possibilities of haipo, injecting new life and energies into this 19th century art-form. Standard innovation rhetoric. The above statement assumes that 19th century haipo production was a consistent blob of something against which Pule could masterfully innovate. Paperskin reveals rather crushingly that this was not so. From around 1880 every Pacific culture engaged with Western influences with an enthusiasm, verve and an imagination that makes Pule’s innovations seem dainty by comparison. Of course, this doesn’t fit with prevailing ideology, and consequently Te Papa under-plays these developments just as the City Gallery over-plays Pule’s.

Another label reads: A persistent theme of these paintings is the inner life of the artist overlapping with and enriching the physical world in which he finds himself. A lovely sentiment, but what artist worthy of the name does it not apply to? Isn’t that what artists are and do? Vague writing of that sort isn’t even Art History 101. The label continues, somewhat more specifically: At the same time, the work is strewn with the tensions and contradictions of the post-colonial contemporary world. It’s tempting to feel that any sort of world would be less tense and contradictory spared label-writing such as this.

Another label quotes academic Peter Brunt’s description of Pule as the great Hieronymous Bosch of postcolonial modernity, a Eurocentric reference that seems utterly redundant considering Paperskin’s content. Isn’t that tradition rich enough to deserve referents on its own terms and not depend on dead white males to validate its legitimacy? “Postcolonial” is a bit of a buzz-word these days, one of those sly assimilations that imply empathy and a “moving on” when in fact power structures (and their exhibiting cultures) remain intact. There’s a nice story of a conference in Hawai’i a decade ago: one of the indigenous participants overheard the word postcolonial and she asked, feigning surprise, “Oh, have they gone?”. “They” haven’t, and “they” still determine what’s shown, how it’s shown, where it’s shown and how it’s interpreted. Applying “postcolonial” to this reality is as cute as donning sunglasses on the morning of 6 August 1945 at Hiroshima.

Despite the impressive content of these two shows, each of them on their own and in their lack of togetherness represents a huge failure of perception and nerve in 2010. It would’ve been more than fun to mix them up. We congratulate ourselves on becoming a Pacific culture, but if the idea’s to have more legs than the clean green New Zealand mantra, museum culture needs to stop resting on the rather dry laurels of the Eurocentric Modernist assumptions underpinning exhibitions of this kind. As they say, if you’re resting on your laurels you’re wearing them in the wrong place.

Peter Ireland

Recent Comments

Roger Boyce

Peter Ireland's review, unlike the exhibitions he covers, exhibits a fearless display of critical perception and nerve. Ireland's critique of ...

Ralph Paine

Anyway, let's just say that for John the question was always one of becoming: here I am, a Niuean child ...

Ralph Paine

No,the post-colonial condition has never been an epoch sans colonialism; rather, it is an epoch wherein the forms, structures, methods, ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 3 comments.

Comment

Ralph Paine, 11:18 p.m. 12 August, 2010 #

No,the post-colonial condition has never been an epoch sans colonialism; rather, it is an epoch wherein the forms, structures, methods, etc. of colonialism have mutated. Or, if one prefers, it is an epoch wherein the standard versions of colonialism are now

perceived as only one dimension of the process which Marx named 'primitive accumulation', that is, the ongoing capitalistic drive to expropriate the common. It is in this sense that the post-colonial condition is coextensive with neoliberalism.

There are, of course, many forms and paths of resistance to all this, but for some artists and cultural critics the path named 'institutional critique' has been (and remains) of crucial, if not primary importance. We are all by now familiar with the story: the museum is a repository of imperial war loot; the museum is a sepulchre; the museum is a place of measure and command, a place where 'communities' are only symbolically imagined into existence so as the emergence of any actual, viable community may be repressed ... The gallery is a monitored place, like a prison cell or a classroom; the gallery is a disciplinary space... Etc.

And so the question of resistance becomes: how might we change all this; how might we transform these institutions into something else, into something less determined and determining, and thus something more open and democratic? Trouble is, the critique was always already being absorbed and mutated (distorted) by the institutions themselves, and so today the situation has become rather complex and paradoxical in the extreme, especially if one adds into the mix the financial and cultural power of such global phenomenom as tourism and it's linkages with the bienalle/art fair nexus, and with what is currently being refered to as Ethnicity Inc.

Now, it seems to me that John Pule has not been a direct exponent of institutional critique ... Which is not to say that his life and work are somehow apolitical. Rather, it's more the case that John has always been a vocal and active participant in the community- and street-level politics of his various melieu. And if we were to give this politics a name it would be 'identity politics', but it should be noted that John's particular version of this politics has always had as its procedural aim that we end up on the the other side of any and every identity so as to become a whatever-people, and this in a similar manner to how Marx thought that the aim of the proletarian revolution was for the proletariat to destroy itself as a class. In this regard, the politics of the Polynesian diaspora has at times seemed way more interesting and creative than that of the more essentialist and sovereignty-based politics of the contemporary Maori world.

Ralph Paine, 11:18 p.m. 12 August, 2010 #

Anyway, let's just say that for John the question was always one of becoming: here I am, a Niuean child thrown down by events onto the southern most edges of Auckland... How, amongst all this, am I to become Niuean, Polynesian? And I guess that this is where the poetry, the novels, the prints, paintings, and everything else came in: they are all both a means for and a trace of this rather singular process, a process which is at the same time that of a collectivity... As encountered by the spectator and the reader in poster or broadsheet form, or as a mural, but primarily in galleries and museums as installed by curators or dealers, or within books as distributed by publishing networks and designed and printed by technical specialists.

But my point is that such encounters need not be overdetermined by the institutions and networks, that when I encounter artworks like John's I need remind myself that I am quite capable of bracketing off this encounter from within its institutional frame. And in this way I may also disengage from any consideration or assessment of the 'hang' or the wall or the wall text or the containing space. And I am also quite capable of achieving this with a piece of siapo. But what's doubly important is that neither am I going to treat this bracketing off as the overdetermination of my experience. So at some point - the next second, minute, on the way home in the bus, whenever - I will want to unbracket my encounter and bring back in the wall, the space, the institution ... and in the case of the piece of siapo, the village space of its production. In other words, and chances are, at some point I'm going to want to think about the social life of siapo.

Or, because I have visited both exhibitions on the same day, perhaps I will find myself thinking about John Pule's relation with the social life of siapo, which turns out in fact to be quite fascinating, because in its traditional setting siapo is/was produced by women ... Which would indicate to me that John's ability to adopt the lines and motif formations of siapo has something to do with his becoming-woman as an artist...

Anyway, it's a pity there's not more feedback here of the critic's bracketed encounter with the dynamic spaces, lines, words, colours, vibrations, etc. set up within and by the actual, singular works.

Roger Boyce, 8:24 p.m. 16 August, 2010 #

Peter Ireland's review, unlike the exhibitions he covers, exhibits a fearless display of critical perception and nerve.

Ireland's critique of the two shows was,for me, reminiscent of critic Thomas McEvilley's seminal review: "Doctor Lawyer Indian Chief: Primitivism in Twentieth-Century Art at the Museum of Modern Art", which apperared in the pages of Artforum 23, no. 3 - in November of 1984.

McEvilley's negative review of the exhibition - Primitivism in Twentieth-Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern - mounted at New York's Museum of Modern Art,in 1984, and the subsequent splenetic exchange of letters between McEvilley, Kirk Varnedoe and MoMA Director William S. Rubin, began a historically important conversation of the sort that is long overdue in the antipodes.

Perhaps Ireland's piece will get the ball rolling in Aotearoa.

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.