Jodie Dalgleish – 16 March, 2011

Johnson's 'Mirrors' is based on a two-second excerpt of Bizumic's birdsong which she analysed to release its component tones into a chord that moves between the sonorities of different instruments.

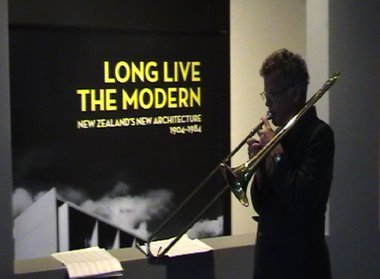

On the 6th of March the Adam Art Gallery’s specially installed, monumental zither in the vault, and its adjoining spaces too, were brought to resonant life. Among a small group of rapt listeners, I was first of all, privileged to hear six musicians perform Mirrors, a composition by Wellington-based musician and composer Hermione Johnson. It was especially commissioned by artist Mladen Bizumic, to accompany his contribution to the Gus Fisher toured Designs for Living (Long Live the Modern: New Zealand’s New Architecture, 1904-1984) and closed an exhibition which was open since October last year.

Johnson herself was on accordion, Gerard Crewdson on trombone, Jeff Henderson on saxophone, Nell Thomas on Theremin, and Chris Prosser and Tristan Carter on violin. Spatially ‘arranged’ along the main vaulted gallery and its axis, these musicians created sounds that uncannily moved with and through the architecture of the entire gallery, making physical and conceptual connections through time and space.

Mirrors was composed by Johnson to match Mladen Bizumic’s installation Holding a Bird in Your Hand and Feeling the Heartbeat, originally part of his exhibition From Cube To Ball (Chapter 1) at the Sue Crockford Gallery in Auckland last February. In that work a ceiling-suspended cluster of blue, red and green plastic lampshades with small speakers emitted field recordings of native birdsong. Alongside them, Bizumic presented fourteen connected yet strangely independent musical ‘notations’ of that birdsong by Johnson. With this installation, the artist referenced his experience of Austrian-born architect Ernst Plischke’s Sutch house in Brooklyn, as well as the coloured lights the architect made part of his design of Christchurch’s St Martin’s Church in the early 1950s. Bizumic had caught sight of the Sutch house when travelling from central Wellington to Brooklyn in a taxi and after stopping on an impulse, he found a chorus of evening birdsong a harmonious counterpoint to its straight lines.

Johnson’s Mirrors is based on a two-second excerpt of Bizumic’s birdsong which she analysed to release its component tones into a chord that moves between the sonorities of different instruments. Technically speaking, she applied a fast fourier transform (FFT) algorithm to a birdsong byte to decompose bird-made notes into their different frequencies, harmonics, or partials. She began her work with the fact that every note is made of many sounds or tones that resonate through air (or whatever medium) over time. And this is particularly fitting given that Johnson’s work sounds something like Bizumic’s, which sounds something like Plischke’s, which relates to the New Zealand modernist tradition presented and explored in Designs for Living. Just as Plischke was concerned with achieving ‘a synthesis of the conception of space and sculptural quality’ in every building, Johnson and her musicians make sound that bounces off every surface in the Adam’s exhibition space and shapes each listener’s sense of it.

When Mirrors was performed, each listener stood in a unique position within the gallery, making each person’s experience particular. I was perched in the middle of the highest and longest part of the gallery containing Long Live the Modern… and mostly unseen musicians were below me.

It began with the joint sounding of spread apart instruments from which grew a plaintive sonic thread that travelled in all directions at once: immediately establishing the highly resonant reach of the building. Then, throughout its eight minutes, that chord was repeated at intervals again and again, drawn out experimentally at the edges by differently placed instruments and different sonic events. I was able to hear nearby instruments play as their sound was whisked, most predominantly, up and away, shifting restlessly below, past and beyond me. Continually, Johnson’s art sounded to confirm the central dominance of the gallery’s vault - the spine of its architecture - while it played with the peripheral spaces that make the body of the building.

The distinctive song of the electronic Theremin was particularly effective. Centrally lofted on the mid-level Mezzanine overlooking the gallery’s vault, it managed to contrast with yet draw out the sonorities of the other instruments, especially the amplified violins and the bowed scrub and scrape of their strings. Also effective were explosive bursts of trombone sound coming from Crewdson as he walked the main gallery’s length. What I heard was the flit and brush of a sound I could only think of as the heart-thump and slowed wing-flap of Bizumic’s bird, made into the shape and pulse of a space for transposition, transformation and reflection.

Johnson’s exploration of resonance at the Adam did not end with Mirrors. She also performed two largely improvised solo pieces on a prepared baby grand piano. Set up in the open room that flows from the Adam’s entrance, the reach of its strings was extended by an aerial criss-cross of piano wires strung from wall to wall. Although Johnson did not intend her solo performance to directly relate to Mirrors, this almost transparent armature referenced the sound-made synthesis of architecture and experience central to its success. It also brought into the gallery an instrument that - more than any other - resonates its harmonics around and out of its substantial body.

By connecting piano strings to overhead threads Johnson was able to pluck them from a distance, as if she was playing an aerial harp. This she left to the end of her performance. Before that, she played at the keyboard to make the most of modified upper, middle and lower strings. Continually belting out a melodious cascade of chords, Johnson made her unexpected spectrum of sound ring and reach towards other parts of the gallery. As she did the life-beat of Bizumic’s bird quickened and became urgent, drawing listeners into the resonant life of the piano and the places it can sound in.

Jodie Dalgleish

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.