Peter Ireland – 8 November, 2011

There are some earlier French photographers who have influenced Aberhart but his style overwhelmingly has its roots in American practice. He's probably fed-up with being automatically shackled to Walker Evans in the way that Tuesday follows Monday, but it's a connection that can fuel a useful debate on the difference between dependence and influence.

America. What this potent name can conjure up! From the promise of a “New World” in the 15th century to the disappointments of a string of disastrous military engagements in foreign lands from the early 1960s, the recent base shenanigans of Wall Street, and a now compromised President, “America” has symbolized every attractive hope and tomb of good intentions known to the human race. Love it or hate it, it’s there, and no one in these narrow isles has been unaffected by its idealism, its glamour and its grand failures.

Aberhart’s of the first generation of New Zealanders to gravitate towards the United States as the shiny model, away from the jalopy decrepitude of “Great” Britain after World War II. No contest. Vera Lynn’s Blue Birds over the White Cliffs of Dover may have inspired the resolve of British Tommies, but peacetime wasn’t going anywhere sexy with a chick called Vera. The pre-Cold War was a conflict of style, and the battle-worn Brits just didn’t stand a chance.

Fast forward to the early 1970s when the vision of an earthly paradise constructed by Hollywood and National Geographic over the previous two decades started to unravel as Pax Americana came to grief in Vietnam. The Baby-Boomer generation learned a skepticism nursed since, but it wasn’t all bad. Some of them began picking up cameras, not to add to the family album but to make art. This world-wide phenomenon was pretty much American-inspired, and it’s not entirely co-incidental to this Aberhart’s America story that the British edition of Beaumont Newhall’s seminal The History of Photography appeared in 1972. It became an essential source-book for those hardy souls clustered consciously or otherwise beneath the PhotoForum banner a decade later.

And what can be conjured up by the name “New York”. In the sphere of art world aspirations the Big Apple was the only place on the planet in the ‘70s and ‘80s - worshiped as much as kiwiland was maligned. That great city provided the only credible models, and to make it with a show over there was O! very heaven. Such infatuation was bound to wane of course, and now the very notion of a centre has gone the way of all flash. Interestingly, back here, of all the art mediums that yearned for the American template at that time, photography is the one that absorbed it most completely and seamlessly, and it says something about the status of the medium - still - that this phenomenon remains unacknowledged.

There are some earlier French photographers who have influenced Aberhart - Charles Marville, Adolphe Braun, Atget among them - but his style overwhelmingly has its roots in American practice. He’s probably fed-up with being automatically shackled to Walker Evans in the way that Tuesday follows Monday, but it’s a connection that can fuel a useful debate on the difference between dependence and influence. It could be a clue to the outcome here that a case for dependence is just too easy to make. The hugely colonial thread woven through Aberhart’s work - indeed, its very spine - is hardly a feature of Evans’, and the latter’s socialist impulse generating the heat at his cool imagery’s heart has seldom been a conspicuous element in Aberhart’s. And that’s just for starters. You can’t judge a book by its mother.

Whatever the cause - post-colonialism, globalisation, Oprah Winfrey - over the past couple of decades the relationship of New Zealand to the rest of the world has changed radically. Before that it was the humble client of just about anywhere going - the classic “colonial cringe” - with the automatic assumption being that anything done here would be lesser than stuff from elsewhere. Anyone with something to prove had to leave. Remaining in the dock of New Zealand culture could only end in a verdict of “guilty”. The blind, flightless kiwi was the perfect symbol for a nation of losers, and the occasional trumpeting of “overseas success” might bring comfort but could do nothing to alleviate our condition “out here”. Now the world’s our oyster, and the feed’s neither here nor there.

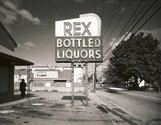

Aberhart’s had two Fulbright Fellowships, one in 1988 and the other last year, and this exhibition provides an opportunity to compare the two bodies of work. The copy of his 1989 album of 10 images In the Southern States of America is, undoubtedly, a homage to Walker Evans, and although there’s no hint of self-abasement, there’s still a slight sense of a self-consciousness that is entirely absent from the 2010 work. In terms of the subject matter there are several Walkeresque motifs - Portland, Maine, 10 August 2010 and Lowell, Massachusetts, 10 September 2010 - but they’re much less homages to Evans than Notes Towards a Definition of Laurence Aberhart.

The new photographs seem more relaxed about their formalism, and their visual frugality is in marked contrast to the relentless accrual of obese debt characterizing the nation over the past three decades. It’s as if the relentless air-brushing of the marketers and other spin-doctors has been stripped back to what used to be known as the real: the simple and enduring. This austere imagery doesn’t lack Aberhart’s signature sly humour though - for instance, who would’ve imagined a new series on Mexican food trucks in New England? - and his radar for unimaginably rich conjunctions of detail is clearly a gift that keeps on giving.

This confluence of the formal and funny points to another gift, a unique present that photography can offer: there are countless instances here of what in painting would be described as “abstract formalism” and “folk art”, where, were they combined, would be as incongruous as a Frizzell one-liner turning up smack bang in the middle of one of Mrkusich’s Bruckner-like symphonic surfaces. But Aberhart does it time and time again, and so seamlessly that no one notices. This fabulous conjuring act is at the heart of photography, a miraculous combining of fact and fable that must banish assumptions about the crude realism often ascribed to it. The shiny surfaces may suggest cartography but the depth of the imagery implies a layering to confound any geologist.

America, like New Zealand, is a nation described by photography. In this show Aberhart includes three images that reference this construction. Interior, Boot Mills Museum, Lawrence, Massachusetts, 10 September 2010 depicts either a painting or a shallow diorama of a c1800 harbour scene, but reflected in its surface is another image, that of an opposite wall featuring an angled series of 19th century portraits. There are, apparently, technical devices to avoid such imperfections. But in Aberhart’s hands these literal reflections find new employment, bringing to the image wider and deeper sense, and restoring, in part, the muse to museum.

In Kodak building from Orchard St, off Lyall Ave, Rochester, New York, 2 September 2010 the viewpoint is definitely non-tourist. The building, famous “home” of photography since the 1880s, is far off to the right, the whole scene framed by a set of steel-framed windows, the grid seeming to be the photograph’s subject. Some of the panes are broken. Do these forlorn lenses suggest the limitations of the medium? Some kind of ‘frame-up” of truth? Or maybe it’s a photographer’s lament for the passing of analogue photography. This ain’t no snapshot baby.

For a medium so often thought of as real, it’s a rich fiction that it has a founder and an actual birthday: 19th August 1839. And the man has a monument in America’s Capital, itself an imaginative construction. Aberhart’s Monument to L.M. Daguerre, Washington D.C. 12 September 2010 is a telling image in all senses, not least for its being a memorial to remembering. In acknowledging an acknowledgement, the photographer has recorded the fact of this memorial’s existence in his usual dead-pan manner. The woman garlands the bust of the photographer in much the same way as Aberhart garlands the reality - paying his homage to a significance out of all sight.

Peter Ireland

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.