Peter Ireland – 9 March, 2013

Brisbane

Fergus Cunningham

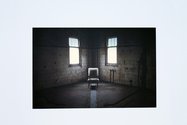

Stilled Life: eight recent photographs

22 February - 6 April 2013

The day before Wellington-based photographer Fergus Cunningham’s show opened in Brisbane there was a front-page article in the New Zealand Herald about growing steroid use in the so-called fitness industry. Ignoring the potential severity of long-term health risks, increasing numbers of young guys are resorting to these drugs in their eagerness to look good, and fast. If the object is to bulk up, why waste energy on exercise, why waste time on waiting? “Health” and “fitness” are “positive” words in marketing terms, but, whatever’s going on in gyms, a lot of it seems to involve vanity and risky practices. What those big mirrors really reflect involves dreams, desire and delusion.

Along with many words vanity’s undergone some shifts in meaning over the centuries, and its use today is more likely to make you think of peacocks rather than futility. Being vain and something being in vain are quite different concepts, and the now frequently misunderstood quotation from the Book of Ecclesiastes is actually about the latter. “Vanity of vanities; all is vanity” simply means that all effort is futile, everything is meaningless. The compilers of the King James Bible in the first decade of the 17th century weren’t thinking of what improvements bench presses might render. But, maybe, on the other hand, the weight room could be where the two concepts finally meet.

This elegiac concept of futility is where the vanitas tradition in art comes from, itself part of a long tradition of recognizing the brevity of life and the ultimate pointlessness of endeavour. Such a recognition tends to be suppressed these days in a Mary Poppins push to rid the world of apparently “negative thoughts”. The vanitas tradition came staffed with guttering candles, blooming flowers, fluttering butterflies, gaping skulls and all the rest - images of transience, harbingers of death and decay. By the 19th century, as worldly materialism smothered belief in a beyond, the tradition died out, but in the current period after Modernism, with its fondness for quotation, the vanitas is undergoing a revival, and it seems especially strong in photography. It may or may not be a coincidence that many of the vanitas works of the 17th and 18th centuries were the most “photographic” works of their time in their attention to detail and commitment to conveying the real. But that’s another story, one risking becoming mired in the awful bog called realism.

The vanitas tradition is a conspicuous aspect of Fiona Pardington’s current practice, the images recalling and refreshing it, but treading the perilously fine line contemporary “art photography” is prey to - pleasing the art crowd but without challenging their fragile preconceptions as to the nature of the medium. Cunningham’s starker work is more likely to be less pleasing but is perhaps more firmly in the vanitas tradition in its aim to warn about the transience implicit in decay. It’s the difference between learned quotation and insistent prophesy. Besides, Cunningham’s work is a fresh reminder of a photographic tradition, of documenting the facts of the physical world in such a way as to suggest realities not subject to being confined by mere visual reportage. This documentary tradition, so central to photography’s histories, has never been much in fashion with art collectors. Not only is it too literal for their taste, the sorts of issues it deals with are likely to make them uncomfortable personally and embarrassed in the company of their friends. Collecting is, after all, more of a social activity than a cultural one.

The self-taught Cunningham’s virtually unknown, but for the past decade or so he’s climbed fences, gone down flaking roads, bypassed rows of orange cones to explore sites and buildings such as provincial schools and hospitals abandoned as a result of the reforming agenda of Rogernomics. He’s driven by curiosity as much by any sense of mission, so that the accumulated work has nothing preachy about it. It just happens to be a devastating revelation of the effects of a huge, largely unforeseen but widespread social readjustment. The empty, trash-ridden and decaying interiors are powerful symbols of another interior, the space of the social conscience at the heart of the social contract: a commitment to strive for the greatest good for the greatest number. The empty spaces Cunningham photographs are not just devoid of purpose, they potently symbolize another emptiness, the lack of any prevailing social conscience that might contract the widening gap between the powerful and the powerless. Not many of the latter have Fiona Pardingtons in their collections. (Nor Fergus Cunninghams, for that matter.)

Photography’s documentary tradition that Cunningham’s images add to has never been very fashionable in terms of art collecting, for pretty obvious reasons. Why tolerate a stone in your shoe when you can simply buy another pair? Documentary may not be fashionable, but it’s never been irrelevant, and it survives with a vigour beyond the needs of any imprimatur from the art world. Its needs are not the needs of art historians, collectors, careerists or auctioneers.

The eight images in Stilled Life take the photographer’s work a stage further from his plainer, site-specific imagery of recent years, and suggest a slightly more adventurous approach. It’s as if he’s realized the import of what he’s been doing and has written that into the script, making the newer imagery both less geographically identifiable and more redolent of its symbolic implications. Individually, where they are has become less interesting than what they mean. While each photograph has its own autonomy - and individually they’re more mysterious - collectively they’re more than the sum of their parts, living up to the show’s title with a sometimes chilling precision. The lushness associated with Dutch still life is here replaced by an unalloyed bleakness making no bones about its intent.

An apparently odd man out is an image entitled Tapu, the subject matter involving the altar in a tidy space, the site of worship for a still-functioning religious congregation. The word “tapu” is emblazoned three times across the front of this sacrificial table, an indigenous replication of the traditional Latin inscription “sanctus, sanctus, sanctus” (holy, holy, holy). This bright and uncharacteristically unabandoned interior is made darker by one of the broader meanings of “tapu”: not only sacred but forbidden. It’s the same message given out by those gym mirrors, except what’s forbidden there is any thought of mortality, any reflection on the slow decay that inevitably mocks all striving for physical perfection. More traditional vanitas imagery, however, manifests itself in the remarkable photograph Der Tod, which depicts, literally, a skeleton in a cupboard. In this scenario there are skeletons in the cupboard all right: the health and fitness industry’s vanity preoccupation, gym-goers’ determination to keep at arm’s length any reflections of mortality, the art world’s reluctance to greet photographic imagery that might disturb the comfortable assumptions of its clients and, indeed, its own assumptions about the nature of the medium.

In an acerbic, stimulating and hugely entertaining article entitled The State of New Zealand Art by Wellington journalist Rosemary McLeod published in the November 1986 issue of North & South magazine there’s a box called Art ratings: who owns what. In it she presents pithy assessments of what various groups of people collect. For instance, under Art Buffs are listed “Mrkusich, Walters, late Colin McCahon, early Toss Woollaston”. Under The Rich are listed “Rita Angus, late Toss Woollaston, early Colin McCahon”. You’ll begin to get the idea. The final listing, under the heading Good For Foyers, has a single entry: Gretchen Albrecht. This is not an altogether favourable observation. But it can be: Fergus Cunningham’s images would be good for foyers. Gym foyers.

Peter Ireland

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.