Terrence Handscomb – 20 August, 2014

There is a quiet anger in 'Uhila's 'Mo'ui tukuhausia' and its critical placement in the show provokes a wider antibourgeois narrative: I wouldn't mind the $50K in my pocket, but FFS don't burden me with your taste, your conversation, your unnatural facile criticality, your penchant for safe art and the number of obstacles you set up so that you may elevate your rentier benefaction by branding my work as 'outstanding'. If the Walters prize is ‘NZ's toughest art prize,' then in fairness, it should be equally tough for the patrons.

Auckland

Simon Denny, Maddie Leach, Luke Willis Thompson, Kalisolaite ‘Uhila

The Walters Prize 2014

12 July - 12 October 2014

The most revered and reviled text on wealth and inequality in recent times, is undoubtedly French economist Thomas Piketty‘s master work Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard (2014); Le capital au XXXI siècle, Éditions du Seuil (2013)). Piketty makes a powerful case, which if true, means that the gap between rich and poor in the twenty-first century will return to the extremes of wealth and poverty last seen in fin de siècle Europe.

Piketty forecasts the twenty-first century reemergence of a petit bourgeois society of rentiers (from the French noun rent: private income, annuity etc.) whose accumulated ‘patrimonial wealth’ will result in an economy driven by inherited wealth rather than merit. If the gap between growth and return on capital widens, as Piketty forecasts, then birth, marriage (and divorce for that matter) will matter more than effort or talent [1].

If Piketty is correct, and a new Belle Époque of wealth inequality deepens, the traditional relationship between art and money may plausibly incite an arts critical insurgency; that is, an antibourgeois subclass of bohemian writers, artists and musicians whose sole purpose is to make the sort of art that would bring down any bourgeois society predicated on wealth, privilege and difference and the sort of culture this will instigate: the reemergence of the historical avant-garde.

For this reason alone, the critical juncture that is the Walters Prize, replete with cultural contradictions and of course the rentier capital that funds the $50K prize, gives plenty of room for discussion. More so, given the finalist inclusion of Kalisolaite ‘Uhila’s outstanding ‘plight of the homeless live artwork’ Mo’ui tukuhausia (2012) and the cultural and economic wealth inequality this work entails — people are homeless because other people have all the money.

I therefore find no problem in mocking cultural difference and wealth inequality by summoning the fin de siècle stereotypes of bourgeois and bohemian. Much to the chagrin of his many critics, Piketty summons the ghosts of Jane Austen and Honoré de Balzac to characterize the texture of wealth inequality. There is a quiet anger in Mo’ui tukuhausia and its critical placement in the show provokes a wider antibourgeois narrative: I wouldn’t mind the $50K in my pocket, but FFS don’t burden me with your taste, your conversation, your unnatural facile criticality, your penchant for safe art and the number of obstacles you set up so that you may elevate your rentier benefaction by branding my work as outstanding. If the Walters prize is ‘NZ’s toughest art prize,’ then in fairness, it should be equally tough for the patrons.

It is never wise to bite the hand that feeds and then inject it with the venom of resentment, but if Piketty presages truth, then the distance between private patronage and artist’s independence will only widen. The sort of antibourgeois art mustered by the historical avant-garde will increasingly appear. This will especially be the case if incisive critical art continues to be commodified by bourgeois interests. Simon Denny’s work All You Need Is Data — The DLD 2012 Conference REDUX (2013) has already been commodified by the very forces that it seeks to mock.

Ignoring for the moment the pantomime of giving away money — the prize-winner-announcement dinner that will be mainly attended by those who have enough money to buy an exorbitant gallery fund-raiser ticket — that somehow ends up privileging the already privileged, the Walters Prize can feature interesting works and provoke debate. 2014 is no exception. Consequently, I have tasked myself here with a critical unpacking of Maddie Leach’s Walters Prize finalist work If you find the good oil let us know (2012-14).

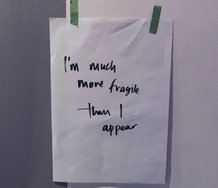

Leach’s work, and its defiant minimalist dislocation from the gallery, at a time when it should be present to impress a judge, makes an important statement. This is because the whole project, including its history, entails what I see as an artist’s act of willful disengagement. This interests me.

The original iteration of Leach’s work — it is more accurate to say its process — began by discovering a substance thought to be whale oil and a narratological investigation unfolded from there. At no point has this object been housed in a gallery. Ironically this has been emphasized in gallery publications in establishing the project’s relationship to the gallery. It is difficult to see how Leach’s work would be shortlisted for a major art prize if the project had not already been associated with a gallery — in this case is the Govett-Brewster through an artist’s residency. Even though Leach chooses a minimal material presence for the Walters Prize exhibition — a newspaper advertisement and her personal website — the object of the work is indeed present. The absent object has become a placeholder for a conceptual back story that has been incorporated into the rhetorical body of the Walters Prize. As such, the minimal presentation on show becomes an element in a state of representation, which in this case, has been constructed by the Walters Prize organizers. Back stories in art are easily co-opted as objects in states of representation that are always in excess of the things presented.

While not entirely imbued with the same ‘post-object’ intentionality as Kalisolaite ‘Uhila’s and unlike Denny’s forceful visual presence, Leach’s Walters Prize presentation (the artists themselves determined how they wanted their work presented to the judge) demonstrates a typical New Zealand subtractive staunchness and unwillingness to look fabulous (Leach’s rhetoric has always given her plenty of moral distance from such facile engagement) that would otherwise give their projects the sort of libidinal presence that could win over a lazy judge. Upritchard was good at that, it probably worked for Yvonne Todd and Denny clearly has it. NZ artists living overseas seem to quickly get over the unspoken imperative: do not make big, flashy, complex nor intellectual art and above all, respect the grunge!! As I see it, this condition lies deep and it continues to haunt the Kiwi cultural psyche.

An alternative back story for Leach’s staunch reductionist ethic — not the one constructed by the custodians of the Walters Prize — is one that sees it as a tightly localised discourse; a genus of what Quentin Meillassoux calls ‘community solipsism’ [2]. Besides this, Leach’s objective dislocation marks a sort of libidinal denial that traces legacy to the mean-spirited retaliatory feminism of the late 1980s — a legacy also traced to the early work of Vivian Lynn and Merylyn Tweedie and the provocative writings of Lita Barrie. Although Barrie’s engagement with New Zealand arts culture was relatively short, it was in its time, ruthlessly effective. Barrie’s feminist motivations spawned sadistic subtexts, but her humour, blended with a stiff mix of libidinal taunting (something totally lacking in Tweedie, repressed in Leach and dark and complicated in Lynn) always opened masochistic back door escapes for her male adversaries.

In the spirit of Luce Irigaray, Barrie was clever enough to effectively toy with her quarry, whereas both Tweedie and Leach continue to choose high moral ground to seed their post-structural feminist sentiments, now twenty years out of date. From high they communicate resentment and disapproval of their (not necessarily) male adversaries with a humourless tone of cranky pissedoffness [3].

Ironically however, Leach’s reductionist decisions could work in her favour. Presenting one’s work effectively always involves aleatory choices. The Walters Prize is, after all, meant to be NZ’s ‘toughest art prize’ and it’s often tough to hit the right note. Despite her resolute, defiant, almost-post-object reductionism and the rhetorical dislocation of her gallery presence, Leach’s presentational choices may well turn out to have unexpected hooks and deliver her the $50K — after all, Dan Arps was an unexpected previous winner and Yvonne Todd won when everyone though it would go to Michael Stevenson. A win could thereby mollify her long-held vocal disapproval of more successful male artists, although my evidence for this is purely anecdotal. For non-art reasons and everyone’s sake, I hope this is Maddie’s time.

Whether the international judge, Charles Esche, recognizes the conceptual fabric of NZ’s peculiar community solipsism with its pathological tendency to hide its face to the world, travelling from overseas to judge an important prize should still require a judge to have enough patience to unpick the symbolic fabric of NZ art’s cultural psyche. To outsiders, that is, those outside the solipsistic circle of a small and still quite isolated art community (I am ignoring the inflated importance placed by NZ gallery owners on their rush to international art fairs) NZ reductionist art may appear no more than a collection of broken signs; i.e. a pathology of names without objects and concepts with dislocated or withdrawn referents.

Without doubt, there is a sort of unanalysable self-effacing jouissance or joy that comes from excessive reduction and displacement, which NZ art seems to be relishing at the moment. As I see it, this is a species of what Lacan called désabonné à l’inconscient, the jouissance or the pleasure of dislocating (literally ‘unsubscribing’) language from the unconscious: this is how Lacan describes the symptom [4].

Hopefully Charles Esche will research this stuff — his short catalogue note suggests he may — and recognise that NZ reductionism has its own peculiar conceptual, cultural and psychological etiology. This may not be easily recognisable nor understood under standard trans-national art evaluation models. Although this pattern is usually denied, these evaluation models in the arts are deeply ingrained and tend to reward flashiness, catch-phrase criticality and defer the importance of single works to the international reputations of artists (no members of the independent jury had actually seen Denny’s All You Need Is Data ... etc. when they short-listed it). If this is the case, Denny’s work is a shoo-in for the prize and the emphasis of post-object art favoured by the independent jury and the dislocated choices made by the other three artists, will have been in vain. I hope not. Despite the call for discourse and critical engagement made in the Director’s Introduction to the exhibition catalogue, whichever artist walks off with the $50K prize and the momentary prestige it brings, the win will eventually lose any critical substance it may have and be subsumed by the sort of sloganeering favoured by arts patrons and institutional custodians: ‘outstanding work of contemporary art.’

Who really knows! Kalisolaite ‘Uhila should win, I hope Maddie Leach does win and I have absolutely no idea how to place Luke Willis Thompson’s work, so I assign him the wildcard slot.

Even ignoring Denny’s offshore mythology, the well-layered content of his installation and despite its annoyingly dated skeuomorphic metaphor (thanks to Apple’s chief designer Jony Ive and the untimely death of Steve Jobs), compared to the staunch minimalism of the other installations, the inflated presence and visual confidence of Denny’s showpiece alone makes me think that he will probably win.

If the gap between rich and poor widens, as Piketty portends, art will simply become ancillary to a new capitalism. The momentary prestige and six month’s salary guaranteed by a Walters Prize win, may indeed engender bohemian mythologies whereby artists may see themselves as cultural heroes. Realistically however, as French theorist and publisher Sylvère Lotringer cynically laments: … there is no more artist life, only another regimented profession. [5]

Terrence Handscomb

[1]. In particular see the sections ‘The Society of Petits Rentiers’ and ‘The Rentier, Enemy of Democracy’ (pp. 418-24).

[2]. Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: an essay on the necessity of contingency, Continuum (2008), p. 50.

[3]. Despite my satirical tone, we should not overlook the pertinent analysis of first-wave feminist Virginia Woolf : “… when a subject is highly controversial — and any question about sex [gender] is that — one cannot hope to tell the truth.” Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, Harcourt (1929), paragraph 1.

[4]. Jacques Lacan, “À l’ouverture du 5e Symposium international James Joyce,” 16 June 1975.

[5]. Sylvère Lotringer and Paul Virilio, The Accident of Art, Semiotext(e) (2005), p.65

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Here is an excellent discussion of the Walters Prize: an interview with Anna-Marie White. http://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/anna-marie-white/?preview=true

Terrence Handscomb

(Handscomb comment continued) “...six month’s salary ...” is a determinate choice of words which veils an insult that alludes to ...

Terrence Handscomb

For some time the monetary value of the Walters Prize has been touted as the equivalent to a years salary, ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 7 comments.

Comment

P.R. Wareing, 7:21 p.m. 22 August, 2014 #

A most interesting piece of writing. Thanks

John Hurrell, 5:35 p.m. 20 September, 2014 #

Here is an excellent discussion of the Walters Prize: an interview with Anna-Marie White.

http://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/anna-marie-white/?preview=true

Kate Linzey, 10:30 p.m. 22 August, 2014 #

Given your reference, I can't help but mention, the median NZ income these days is just under $44k. The Walters represents at least 12 months income for most people, 'professional' or not.

Terrence Handscomb, 11:26 a.m. 27 August, 2014 #

For some time the monetary value of the Walters Prize has been touted as the equivalent to a years salary, with the national median as its datum.

When the ratio of private debt-to-GDP is as high as it is in NZ (although it is currently in the middle of the OECD pack, it is still high and should not be confused with government debt-to-GDP which is relatively low), which when coupled with NZ’s exceptionally high cost of living, it is extremely difficult to live comfortably (everyone’s right) within or below the national average, currently about NZ$55K. Bottom-line lay economics: too much of our personal income goes to someone else (the bank, the landlord, the shareholders ...) who expect healthy capital return on their investment (the value added excess which in simple language is plain old fashioned greed). This is a fiscal form of what I am calling ‘errancy of excess,’ the principle motif of the Walters Prize (my semiotic corruption of Badiou’s ontology. Excess: the measureless difference of power between a state (of representation) of a situation and the situation itself).

Too much and too little is the fascinating mien of the Walters Prize. The Walters is a strange beast that takes awfully-Auckland-petit-rentier-money as bait, then constructs a hysterical cult of anticipation. This is then cleverly woven into the already-over-inflated-state-of-representation that is twenty-first century art and its transnational avatars.

The cultural prudence and quieter patronage of old money (Adam, Hirschfeld, Turnovsky and, to a lesser extent, Gardiner), when it doesn't interfere with process or outcome and is directly tethered to name and place, seems to entail little or no symbolic excess. The Walters Prize on the other hand is quite a different beast, which appears to require intense and continued symbolic feeding. For the finalists, judges, jurors, organizers and patrons, the Walters Prize is a critical production of control, risk, anticipation and excess whose staging demands, and gets, much public attention.

Terrence Handscomb, 11:28 a.m. 27 August, 2014 #

(Handscomb comment continued)

“...six month’s salary ...” is a determinate choice of words which veils an insult that alludes to a ruse:

Should our top (‘exceptional’ is the favored nomenclature) artists whom, irrespective of tenure are at the top of their profession, be rewarded with half a professional salary. Here ‘professional’ should mean ‘executive.’ A dated class based objection entails the assumption that artists are workers and they should be grateful for any benefaction from above. A year’s comfortable cost of living (NZ$100K) is too much to give away at once, so make it smaller but do not say ‘a year’s income for a skilled worker or entry-level professional’ because ‘median annual income’ sounds better. Besides, ‘uncomfortable annual cost of living package for a professional at the top of their game,’ does not sound grand enough for NZ’s toughest art prize.

To many New Zealanders, NZ$50K sounds a lot. As long as the winner is represented as a cultural hero in top form, then everyone will be happy. Ironically, it is the patrons that appear to have most fallen under this spell: “The pull, the glamour, the giddiness of it all is too strong for anyone to resist. And at the same time it’s just crude business deals and shady calculations. It’s become no different than anything else” (Lotringer and Virilio, 2005 (65)). This is the errancy of excess.

Nicholas Haig, 2:15 p.m. 25 August, 2014 #

A super article, but I wonder what's so 'only' about regimented professions?

Daniel Webby, 2:37 p.m. 26 August, 2014 #

A few additional footnotes?

Thomas Piketty on the language of class;

"The concepts of deciles and centiles are rather abstract and undoubtedly lack a certain poetry. It is easier for most people to identify with groups with which they are familiar: peasants or nobles, proletarians or bourgeois, office workers or top managers, waiters or traders. But the beauty of deciles and centiles is precisely that they enable us to compare inequalities that would otherwise be incomparable, using a common language that should in principle be acceptable to everyone."

Piketty again on hypermeritocracy;

“The second way of achieving such high inequality is relatively new. It was largely created by the United States over the past few decades. Here we see that a very high level of total income inequality can be the result of a “hypermeritocratic society” (or at any rate a society that the people at the top like to describe as hypermeritocratic). One might also call this a “society of superstars” (or perhaps “supermanagers,” a somewhat different characterization). In other words, this is a very inegalitarian society, but one in which the peak of the income hierarchy is dominated by very high incomes from labor rather than by inherited wealth. I want to be clear that at this stage I am not making a judgment about whether a society of this kind really deserves to be characterized as “hypermeritocratic.” It is hardly surprising that the winners in such a society would wish to describe the social hierarchy in this way, and sometimes they succeed in convincing some of the losers.(…)

...It is therefore essential to understand the conditions under which each of these two logics [supermanagers and rentiers] could develop, while keeping in mind that they may complement each other in the century ahead and combine their effects. If this happens, the future could hold in store a new world of inequality more extreme than any that preceded it.”

Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Harvard (2014)

Keller Easterling on resistance in the space of mediation;

“Yet however nourishing these critiques of the pervasive market spectacle may be, the stories in this book do not focus on the market's monolithic holism. Nor do they portray a resistance that can heroically match the purity of modernism. They explore instead the backstage networks that Bruno Latour has called "the unconscious of the moderns" - the space of mediation rather than the space of the singular or pure.”

Easterling again on comedic pirates;

“This is an imagination that is opportunistically fascinated with contagions that spawn the most unlikely epidemics of belief. The pirate who is too smart to be right respins the abundant psychological weaknesses, comedies, loopholes, and errors in the market, for partial, perhaps huge, but never totalizing effects.”

Enduring Innocence, MIT press (2007)

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.