Megan Dunn – 22 January, 2015

No one can say Curnow pandered to the powers that be. “What you can write depends on what the culture will allow you to write,” he told the audience at City Gallery. “Language is unpredictable, slipping, sliding…” As the author of works both unpublished and published in places inaccessible in the culture, I felt a grim shudder of recognition. But in the aftermath of Charlie Hebdo and the online debates circulating about the rights and responsibilities of free speech, his words are a reminder. Language is loaded and the context extracts the charge.

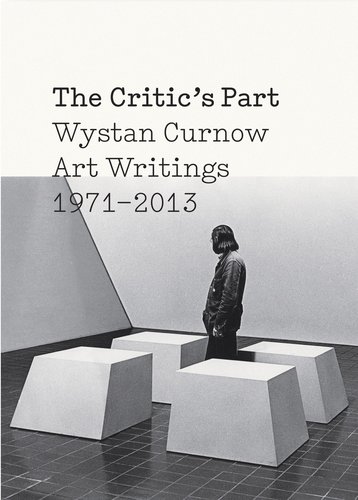

The Critic’s Part: Wystan Curnow Art Writings 1971 -2013

Ed. Christina Barton & Robert Leonard, with Thomasin Sleigh

Two introductions by Barton and Leonard; timeline by Sleigh

Hardcover, 512 pp, b/w illustrations

Designed by Alice Baxter

Published by Adam Art Gallery and VUP, 2014

“We’re in a language war,” Wystan Curnow said at the City Gallery book launch for The Critic’s Part; “everything you put down is marked in some fashion or another.” At the time of the launch last November I was partly in a war to finish and review The Critic’s Part, but my intellectual arsenal was depleted. I felt like Private Benjamin sent onto the set of Apocalypse Now.

The Critic’s Part represents over 40 years work; it is in essence my age. Edited by Tina Barton and Robert Leonard, the 38 essays and texts included in this collection are organised chronologically from 1971 to 2013; the book also contains a bibliography of Curnow’s writing and a time line collated by Thomasin Sleigh.(2) At the launch Curnow said The Critic’s Part, “rescued pieces from places inaccessible in the culture.” Quite. By consulting the back of the book I learnt that Curnow co-edited the short-lived magazine Splash and was a contributing editor to Parallax.

“The New Zealand mind has an unhealthy distaste for theory,” Curnow wrote in 1973. High Culture in A Small Province established the terms and conditions for Curnow’s own criticism and is the structural backbone of this collection, which culminates in High Culture in A Small Province: Further thoughts 1998-2013. The original essay is an uncompromising argument for expertise, richness and difficulty in the arts or in the words of Curnow’s former tutor Morse Peckham, “innumerable ambiguities and ambivalences and puzzles and problems.” The high mindedness of the first High Culture essay continues to exert a powerful wish fulfilment: the desire for the artist to concentrate undisturbed on his art, and for the critic to follow him, providing ‘psychic insulation.’ Although Curnow now joked that he was, “…against specialisations. I might just have been wrong back in 1970.”

At City Gallery he read from High Culture Now! a 1998 manifesto that is equally playful, pointed and abstract: “…art cannot belong entirely to culture because it also sets the terms of what art might be thought to be.” The 12 points of this manifesto are a dialogue fit for the Cheshire cat but were supposedly written ‘for’ the law firm Hesketh Henry and first addressed to a stakeholder meeting gathered to discuss a visual arts infrastructure review. I wonder if the stakeholders agreed with point 9: a rapier delineation of the difference between art sponsorship and patronage delivered in faux-business speak. “Sponsors want gratitude - it adds value.”

No one can say Curnow pandered to the powers that be. “What you can write depends on what the culture will allow you to write,” he told the audience at City Gallery. “Language is unpredictable, slipping, sliding…” As the author of works both unpublished and published in places inaccessible in the culture, I felt a grim shudder of recognition. But in the aftermath of Charlie Hebdo and the online debates circulating about the rights and responsibilities of free speech, his words are a reminder. Language is loaded and the context extracts the charge.

So what did our culture allow Curnow to write? Judging by the breadth and depth of The Critic’s Part he succeeded in “…producing a reader one wants to be out there and more of them.” As Leonard noted in his own introductory speech Wystan “… was never a gun for hire. He wrote about what he wanted to write about, saying what he wanted to say. He always had an agenda - to push the argument this way or that.” That agenda was (and perhaps still is) to “generate new forms of thought and feeling.”

For an informed art audience the importance of his American tenure and subsequent return to New Zealand in 1970 don’t need to be overstated. It’s all in that title: High Culture/Small Province. However, Curnow’s interest in L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry and education in literature (he did his PHD on Herman Melville; who knew the dude who wrote Moby Dick wrote poetry?) meant he was unusually well placed to produce such an elastic body of criticism.

Tina Barton identifies Curnow’s approach as one of ‘immersion’; “a point where the distance between work and words, object and perceiver, and inside and outside enfold.”(3) At the ‘critical juncture between modernism and post-modernism’ Curnow’s writing flexed to better reflect contemporary ephemeral forms including performance and post-object art. Yet for a critic so little swayed by the representational, it’s telling that key moments in Curnow’s oeuvre are characterised by mimesis. Literature remains dominated by modes of realism.

The Bruce Barber: Mt. Eden Crater Performance was written in situ… featuring many ellipses…the reader is active…on guard…picking up the scattered breadcrumbs of the performance…in amongst the other detritus Curnow recorded on the day. Curnow’s text is really an attempt to replicate life on the spot, of course artistry shapes the effort, the final form, but the writing represents the necessarily incomplete experience in the crater that day. The first thing I thought after reading this was: I bet the Bruce Barber performance wasn’t even that good. I naturally assumed Curnow’s writing was better.

Did I mention he’s funny? The Critic’s Part begins on a 1971 review of The New Zealand Young Contemporaries. “Did it lay bare great tribes of teenage art talent?” Curnow asks, rapidly concluding, “No it didn’t.” You had me at hello. The frankness and candor of his writing rebuffs the formal registers of academia in favour of the conversational - often colloquial - style of the “new journalism.” Art Places, a series of four travel pieces written for Art New Zealand in the late seventies, crackles with electricity. The details of New York street scenes mingle with casual art conversations that take the reader directly inside the experience - the consciousness - of the author. It’s the old creative writing truism ‘show don’t tell.’ (If Art New Zealand contained more writing like Art Places I’d re-subscribe tomorrow.) Curnow’s gift for dialogue and the spoken word is linked to his double life as a poet. In New York Scene 2 the hooker he passes on route to the subway lingers, “Going out, honey?”

The Critic’s Part builds both a macro and micro view of contemporary art from the unique perspective of an “antipodean internationalist.”(4). Yet despite Curnow’s interest in cartography and his ability to map cross currents between the national and the international (Thinking about Colin McCahon and Barnett Newman, Climbing Rangitoto Descending the Guggenheim), the texts that thrilled me most vividly enlivened local history. Peter Roche/Linda Buis: A Gathering Concerning Three Performances alternates between first person accounts told by Peter Roche, Tony Green and Curnow, creating a picture of each - potentially baffling - performance, its audience and their reactions. The works are experienced from the outside in and the inside out. I especially warmed to Night Piece, a 1981 performance in Freeman’s Bay to which Curnow was the sole witness. Curnow travelled by bus to an abandoned old gasworks site to watch Buis crawl upon the precipice of a derelict building while Roche lit candles in the dark. The critic’s vigil is to stand apart.

I first encountered Roche in the 90s; by that time a mystical Voodoo status had descended upon him. He did the opening performance at Fiat Lux, the artist run space I established with David Townsend in 1996. David had already been involved in a high-octane performance at Roche’s Ambassador Theatre in Pt. Chevalier, which consisted of David sewing his own lips together. Roche reciprocated with an event at Fiat Lux: a pair of chainsaws rotated unmanned across the wooden floorboards, emitting petrol and smoke. A sense of Jaws-like suspense built as the art crowd clustered outside on Hobson Street, watching the predatory movements of the chainsaws through the shop window. Eventually Roche plucked the chainsaws from the floor and the performance culminated when he sawed the neighbours green wheelie bin in half. The family who ran the Chinese takeaways next door - the owners of the green wheelie bin - peered on through net curtains. New forms of thought and feeling were definitely circulating.

There are other - better - readers for aspects of The Critic’s Part. I was a child during half this book’s time span. I come to it now as a gun for hire, a New Zealand mind with an unhealthy distaste for theory. The limits of my own knowledge were at times painfully acute: thou shalt not pass. I fell off the wagon with several of the more complex essays. And I had a shingles-like reaction to the topic of alchemy in Julia Morison’s art. Eventually fashion rejects us all. There are a few names included in this collection that are unlikely to warrant the attention of today’s top art critics. Max Gimblett? Yet the Gimblett essay features two intoxicating dreams, one of Picasso. I had no idea who Tom Kreisler was and nearly skipped this piece. I’m so glad I didn’t. Curnow commemorates Kreisler’s humour with aplomb.

The politics of humour in art writing, who detonates what joke and when, are also at stake throughout The Critic’s Part. Curnow chose Billy Apple as the key artist to ‘insulate’. The book includes four pieces on Apple but it’s the early reception of his work in New Zealand that I found most illuminating. Curnow’s analysis of the media response to Apple, then on tour from New York, is essential reading that is still implicating today. “In the passing on of information smart word play is often self-serving and a form of disengagement. Commonly we find the reporter retreating from his task with cute innuendos from which we are to infer: they can’t be serious therefore we won’t be.” Curnow dissects a barrage of cheap headlines that pun on the artist’s name: Pip Squeak, Billy Apple’s Pickings and my favourite The Apple of his own Eye.

Merde; I often laughed out loud at these headlines. But what does that really say, other than the obvious? Mainstream arts reportage has not moved on substantially from cheap puns in headlines. The terms and conditions of high art continue to remain oblique to a general public that doesn’t subscribe to the same contractual concerns. Often art is purposefully obtuse, that is one of its qualities, as exemplified by the cartoon of a gallery-goer innocently admiring a fire alarm. Can one laugh at contemporary art and also take it seriously? Curnow’s own humour can be just as lacerating, see Identikit Portrait of an Expressive Realist. And Billy Apple is entitled to (invent and) pun on his own name e.g. Billy App. Language - like art - is inevitably shaped in the image of its maker.

In August 2014, I attended an art-writing symposium held by the Adam Art Gallery called Working the Gap. Curnow was the keynote speaker at this event, a status befitting his impressive contribution to criticism. His address was entitled: The Responsibilities of the Writer and the Irresponsibilities of Writing (or Watch your Language, Effendi!). At the end of this multi-faceted address I somewhat irresponsibly asked: “Is there a place for unserious critics?” “There’s plenty of them,” Curnow replied. Fire in the hole! Later still a fellow attendee said to me; “my favourite part was when you heckled Wystan.” “I didn’t heckle Wystan,” I said. Did I?

Megan Dunn

(1) All the quotes from the City Gallery book launch on November 9th 2014 are taken from hand written notes I made on the day; any errors are my own. At the launch Robert Leonard introduced Wystan Curnow; Wystan then read from the book, before answering a Q and A session facilitated by Thomasin Sleigh.

(2) Thomasin Sleigh completed her Masters thesis on Curnow and her research was a crucial resource for the collection.

(3) ‘Notes on Method’, Christina Barton, The Critic’s Part, (P14-15)

(4) ‘Curnow’s Leverage’, Robert Leonard, The Critic’s Part, (P10)

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.