Warren Feeney – 7 April, 2015

'Language is a Virus' brings together artists from Taiwan and New Zealand in an exhibition less concerned with drawing attention to a sharing of practices in the Asia Pacific region than it is with mutual questions and ideas about the reading of images, their status, analysis and cross-examination. Curated by Jamie Hanton, it has its origins in a group exhibition, 'These Stories Began before We Arrived', that Charlotte Huddleston, Bruce E Phillips and Hanton put together when they visited Taipei in 2014.

Christchurch

Chen Yin-Ju in collaboration with James T. Hong, Hsu Che-Yu, Nathan Pohio, Shannon Te Ao (live perfromance) and Teng Chao-Ming (posters)

Language is a Virus

Curated by Jamie Hanton

25 March - 23 April 2015

Although the title Language is a Virus might suggest that this is an exhibition centred upon the written or spoken word it is essentially about images and the visual arts as a unique and persuasive form of communication.

Language is a Virus brings together artists from Taiwan and New Zealand in an exhibition less concerned with drawing attention to a sharing of practices in the Asia Pacific region than it is with mutual questions and ideas about the reading of images, their status, analysis and cross-examination. Curated by Jamie Hanton, it has its origins in a group exhibition, These Stories Began before We Arrived, that Charlotte Huddleston, Bruce E Phillips and Hanton put together when they visited Taipei in 2014 as part of the Asia New Zealand Foundation / Creative New Zealand’s Curator’s Tour programme. These Stories Began before We Arrived included three of the participating artists, and thematically, both share an interest in the complexities of reading the interaction between images and narratives and their layering in personal and cultural agendas.

Hanton’s catalogue essay discusses the issues around such dialogues and the languages and codes that affect and reiterate familiar power relationships. He references William S Burroughs’ The Electronic Revolution (1970) in which the author railed against mainstream media, believing in its ability to control the masses. Hanton dismisses the essentially paranoid tone of The Electronic Revolution, but acknowledges the commonalities between the works of the participating artists and Burroughs’ agenda. There is a shared interest in bringing together seemingly disparate images and texts to undermine assumed truths, encouraging alternative and unanticipated readings and perspectives.

Paradoxically, it is the attention that the exhibition catalogue brings to such theory that disarms the gallery visitor’s need to over-read the imagery in Language is a Virus, instead directing attention to an awareness of its ability to intrigue, surprise and persuade.

Of course such an agenda is hardly new to contemporary practice. The premise of fluctuating open-ended dialogues has been prominent for at least the past decade; for example, in the work of artists like Jordan Wolfson. Yet its positioning in Language is a Virus seems special. The gallery visitor is distanced from the given and familiar and their attention directed to the experience of the exhibition and the self-conscious pleasure and joy of looking and considering anew.

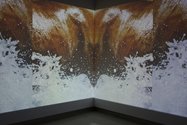

Chen Yin-Ju and James T. Hong’s five-channel video, End Transmission, is a beautiful and concentrated cinematic moment, assembled from a bogus ‘It Came From Outer Space’ storyline that draws together vast panoramic landscapes, fairgrounds, industrial landscapes, mining, intimate close-ups of floating rubber ducks and much more, interspersed with messages from returning invaders from outer space. It is a tenuous sci-fi storyline wilfully acting as a detached and impotent warning about the state of the planet: “We are here so now you must respect this planet, etc.”

The disconnection between the tangible reality of its imagery and the lack of substance in the claims of its texts is essential to End Transmission. It never gives up on its promise of an apocalyptic invasion, but it also never delivers one, preferring to not quite give the gallery visitor the reassuring ‘fiction’ that is assumed to be guaranteed. Even the changing texts in End Transmission are in on this game: ‘You are a stranger on the earth’ simply sounds like the promise of a false epiphany.

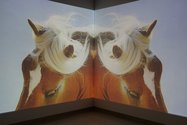

There is a similar intention to undermine expectations in Nathan Pohio’s The Feral Horses of Natasha Von Braun. A split screen of converging, close-up images of a horse captured in slow motion. Pohio’s imagery shifts between My Little Pony, San Francisco 60s psychedelia, a Rorschach blot-test and a scene from a Wild West movie like John Wayne’s Red River. All represent a packaging of the natural world for popular consumption. Pohio comprehends the seductive spirit of such an agenda perfectly. The sweetness, prettiness and attention to the unbridled life-force of the animal is persuasive, yet its parading as cinematic experience to represent full and frank disclosure is more like a warning than a confession - delivered in the nicest and most uncomfortable of ways.

Hsu Che-Yu’s Perfect Suspect consists of a series of five television screens butted up next to one another like an animated comic strip. Yet the implications of any linear narrative are never seriously considered. The action unfolding on each screen seems simultaneously related and disconnected from those it sits beside. Based on a crime report from the artist’s local newspaper, the staccato and repetitive actions of all participating figures only seem reassuring if read as commentary on the absurdity of human behaviour. Figures nodding their heads could be a promise of agreement, a limbering up for exercise or a distancing from all communication. In Perfect Suspect, purpose and outcome is disengaged, rendering all personal interaction ineffectual.

Language is a Virus is an important exhibition. Not just because it represents a kind of revelation about how the visual arts represent a specific way of reflecting upon and revealing the nature of experience, but also because it has been conceived and presented by an academic institution whose priorities are about the capacity of the fine arts to address and comprehend (or otherwise) our experience and philosophies about the world in which we live.

It also follows a series of successful exhibitions from the Ilam Campus Gallery in 2014, but raises its game one step further. This is a show with few precedents in Christchurch. The Ilam Campus Gallery is currently delivering an exhibition schedule with an agenda that, at its best, cultivates serious and animated discussion around issues of importance to contemporary art. The visual arts have rarely been so well provided for by any arts institution in this city.

Warren Feeney

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.