Scott Hamilton – 12 May, 2017

The series of eighteen paintings that Patrice Cujo calls Ol Map Blong Vanuatu can perhaps be considered a belated direct encounter between European Surrealism and Melanesia. By giving Vanuatu's islands a large scale, Cujo ennobles them, in the same way Eluard the Surrealist mapmaker ennobled Melanesia in 1929. However his charts have an anthropomorphic quality missing from the Surrealists' famous map, for the faces and limbs of peculiar creatures emerge from the contour lines of his islands, recalling the ‘picture maps' that were popular in nineteenth and early twentieth century Europe.

Port Vila

Patrice Cujo

Ol Map Blong Vanuatu

Permanent display

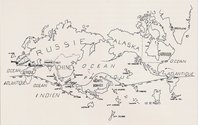

In 1929 the Belgian journal Varieties published a special issue dedicated to Surrealism. The issue included texts by Andre Breton, the movement’s chief publicist, by Paul Eluard, its leading poet, and by Sigmund Freud, its unconscious creator - but is perhaps best remembered for an anonymous drawing called Le Monde au Temps des Surrealistes or The Surrealist Map of the World. The map, which was probably the work of Eluard, presented continents and islands and oceans in unfamiliar shapes and sizes. Europe had shrunk, and become an insignificant peninsula of Asia. The United States had been digested by the Canadian province of Labrador.

The Surrealist Map of the World was a political as well as an aesthetic statement. By the beginning of the twentieth century every African nation except Ethiopia and Liberia was a colony of one European power or another. The French and British had divided much of mainland Asia between them, and in the Pacific only the Kingdom of Tonga had avoided colonisation. When they gave colonies the same colouring as imperial homelands, conventional cartographers emphasised the importance of the northern hemisphere, and the subordinate position of other places. By shrinking Europe to an irrelevance and extinguishing the United States, the Surrealist cartographer mocked his imperiocentric counterparts.

But it was the map’s treatment of the Pacific that was most remarkable. In the 1920s conventional cartographers put the Atlantic at the centre of their worlds, but the Surrealists gave the biggest ocean that honour. A series of Pacific islands, from Rapa Nui in the east to New Guinea in the west, were greatly increased in size. New Ireland, the largest piece of the Bismarck archipleago, was almost as big as Australia, and the New Hebrides were the size of New Zealand.

The prominence of Melanesia in The Surrealist Map of the World was not accidental: the region obsessed Surrealists.

By the beginning of the twentieth century Europe’s museums had acquired many artefacts from the Western Pacific - some were the booty of triumphant missionaries, while others had been carried away by ethnographers and traders - and the continent’s avant-garde artists were learning from Papuans and ni-Vanuatu.

In 1907 Pablo Picasso discovered Pacific and African masks in Paris’ Trocadero Museum. Picasso was excited by the African as well as Melanesian artists, but the Surrealists tended to reject Africa in favour of Oceania. Breton complained that African sculpture was too realistic, and contrasted it with the fantastic carved figures that had come to Europe from Melanesia.

The sculpted Melanesian figures Breton loved often had grossly elongated or shortened limbs. Their faces could be distorted by exaltation or anguish. They might be hybrid creatures, as crocodile or pig as human. They seemed complete and formally perfect, and yet also in the process of transformation into some new identity. “You frighten. You astonish,” Breton wrote, in a poem about Uli, a series of statues of an ancestor figure carved by the Mandak people of central New Ireland.

In the museums of Europe, Melanesian art looked like a counterargument to the orderly bourgeois civilisation that Breton and the Surrealists despised. In her book Surrealism and the Exotic, Louise Tythacott calls Melanesian sculptures “repositories of the dreamlike and the magical” that “transcended oppositions” - between past and present, rational and irrational, human and animal, death and life - that European culture cherished.

Breton and Eluard soon began to collect Pacific artefacts. Breton’s shop Gradiva offered Uli sculptures and other Melanesian masterpieces for sale. In the Exhibition of Surrealist Objects that Breton curated in 1936, sculptures from New Guinea, New Ireland, and the New Hebrides stood beside Surrealist artworks and artefacts of modern American consumer culture. Later in the same year British Surrealists filled an exhibition with Melanesian artworks they had retrieved from their country’s museums.

Yet few Surrealists ever visited the region that preoccupied them. Paul Eluard travelled through Indochina as a young man in the 1920s, but never ventured into the Pacific. Breton knew Melanesia only through artefacts and ethnographic treatises. In the 1930s and ‘40s many Surrealists were pushed out of Europe by fascism and war, but most headed for North America, rather than the southern hemisphere.

The only Surrealist to reach Melanesia seems to have been the Czech painter Dusan Marak, who fled the Stalinist takeover of his homeland and, inspired by The Surrealist Map of the World, travelled first to Australia and then to the Australian colonies of New Guinea and Papua. Marak brought his paintings with him, and in 1954 he even staged an Exhibition of Surrealistic Painting for the planters and missionaries of the colonial capital Port Moresby. But tropical humidity damaged many of Marak’s canvases, and he spent more time counting coconut trees for Australian planters than painting during his years in Melanesia.

The series of eighteen paintings that Patrice Cujo calls Ol Map Blong Vanuatu can perhaps be considered a belated direct encounter between European Surrealism and Melanesia. Cujo was born in the town of Clermont-Ferrand in central France near the end of World War Two, and settled in the New Hebrides in the 1970s, when the Anglo-French colonial regime was being put on notice by a national liberation movement. At the beginning of the 1980s the New Hebrides became Vanuatu, and Cujo helped to found the Nawita Association, which united white and ni-Vanuatu artists. Later he helped the Caldoche educationalist Suzanne Bastien, who had taken a job in Vanuatu in the 1960s and never left, create a gallery in Pango, a harbourside suburb of Port Vila, Vanuatu’s capital. Today the gallery is known as the Fondation Suzanne Bastien, and permanently displays Ol Map Blong Vanuatu.

Ol Map Blong Vanuatu is a phrase of Bislama, the creole improvised by indentured New Hebridean labourers on nineteenth century Australian sugar plantations. Bislama mixes archaic English words like picaninny and savvy with caustic slang, and organises them with an elastic Melanesian grammar.

Cujo’s paintings are large. The smallest, his portraits of Efate and Tanna Islands, are 80 x 120 cm; the largest, his depiction of Espiritu Santo, is 280 x 180 cm in size. By giving Vanuatu’s islands a large scale, Cujo ennobles them, in the same way Eluard the Surrealist mapmaker ennobled Melanesia in 1929.

Cujo made his maps of Vanuatu between 1988 and 1991, first in Port Vila and then during a sojourn in France. Each of his canvases shows one or more islands, using a mixture of paint and collaged materials. However his charts have an anthropomorphic quality missing from the Surrealists’ famous map, for the faces and limbs of peculiar, often humanoid, creatures emerge from the contour lines of his islands. This anthropomorphism recalls the ‘picture maps’ that were popular in nineteenth and early twentieth century Europe.

For example, in an 1899 drawing called Angling in Troubled Waters: a Serio-Comic Map of Europe, Fred W Rose showed a fisherman with a Union Jack vest casting his line into the North Sea, while a set of hostile nations looked on. Sweden and Norway are dogs; the wedge of Russian territory that extends into central Europe is a Tsar’s booted foot; a Prussian general sprawls across Germany.

Fifteen years later, when the long-promised European war had arrived, another British artist, Walter Emmanuel, produced a map called Hark! Hark! The Dogs Do Bark! Emmanuel showed a British bulldog striding across the channel into Belgium, where a thin demented hound wearing a pickelhaube waited.

Cujo may owe something to the satirical maps of artists like Rose and Emmanuel, but he eschews their simplicity and clarity. It is easy to identify the various geographical features in Angling in Troubled Waters and Hark! Hark! The Dogs Do Bark!, and equally easy to understand the maps’ messages. Cujo’s paintings are much more mysterious. He carefully renders the coasts of his islands, and uses contour lines to describe their interiors. But the colours he gives to the islands often make no cartographic sense, and an eerie figure emerges from his intricate lines. His maps are an odd mixture of realism and fantasy.

Cujo painted Espiritu Santo, Vanuatu’s largest island, in 1989 and 1990, when he was living in France. Santo is shaped like the letter L, and Cujo reproduces its outline correctly. The island is covered in hills and mountains, which Cujo depicts with scores of writhing contour lines. He has painted the westernmost parts of the island light green, then used darker, muddier colours for the east. Such colours are sometimes used by cartographers to suggest deforestation and erosion, but Santo, like most of Vanuatu’s larger islands, is still relatively sparsely populated, and retains much of its forest cover. In the southwest of the island contour lines swirl together to make the shape of a human sitting crosslegged. The figure’s torso is wrinkled by topography; its skull-face is contorted in a way that recalls Edvard Munch’s The Scream. A second figure, which has the yellow-grey colour cartographers sometimes reserve for sandbanks and shoals, seems to be diving into the north coast of Santo: its legs and torso can be seen, but not its face or arms.

How might we interpret the eerie figures that emerge from and recede into Cujo’s Santo? The southwest of the island is isolated and poor. Its villages are connected to shops and health clinics by roads of mud and bridges that are regularly erased by floods. The people of the southwest have long complained of neglect from Vanuatu governments.

But a disaffection from faraway governments is not new on Santo. In the 1960s and ‘70s a semi-literate bulldozer driver named Jimmy Stevens created a religious and political movement called Nagriamel, whose members rejected both conventional Christianity and the notion of a Vanuatu state. After receiving money and a radio transmitter from the Phoenix Foundation, a Dutch-American anarcho-capitalist group intent on creating a lawless utopia in the South Pacific, Stevens announced that Santo and several other islands of New Hebrides would secede from the new nation of Vanuatu and form their own state, which would be called Vemarama.

Stevens raised an army in the Santo bush, and armed them with bows and arrows. They held the island for two months in 1980, until soldiers from Papua New Guinea landed with modern rifles and orders from the postcolonial government in Port Vila. A few fatal shots ended the secession of Santo. Stevens and hundreds of his supporters were imprisoned; many of them were tortured. Today the prophet’s corpse lies inside a shrine amidst the ruins of Fonafo, the capital village he built for Vemarama in the Santo bush.

Could the tormented figure in the corner of Cujo’s painting refer to the suffering of Santo’s bush people? Could it be viewed historically, as a reminder of the violence that almost severed the island from Vanuatu in 1980?

Ambrym, an island in central Vanuatu, is shaped like a triangle, dominated by a bad-tempered volcano, and notorious for its sorcerers. Many ni-Vanuatu believe that Ambrymese use the energy of their volcano to create storms and poison enemies. Passengers on ferries grow nervous when they approach or even pass the island, and Ambrymese who have settled in Port Vila have been the target of riots by locals who blame them for illnesses and accidents.

Cujo depicts Ambrym’s blue volcano against a blue sea. A smoke cloud has risen from the volcano; the cloud is shaped like Ambrym, and also looks like a head wearing a wizard’s pointed hat. The face under the hat has a sharp nose, and eyes that look away from the viewer. A mask has peeled from the face: it might belong to a harlequin, or to a bank robber. An armless hand clutches a cup - does it contain kava, that ancient potion of Pacific sorcerers?

Like the Munchian skeleton which emerges from Santo, the magician who floats above Ambrym reminds us of European rather than ni-Vanuatu art traditions. We think of Marc Chagall’s conjurors, of Picasso’s harlequins, of Salvador Dali’s dissolving, translucent faces. But Cujo adapts European imagery to his Vanuatu subject matter. His magician belongs to Ambrym, an island famous for its magic. If Breton and the Surrealists seized Melanesian imagery and aimed it at European audiences, then Cujo borrows from European art according to the demands of his Melanesian subject matter.

I visited Ol Map Blong Vanuatu with Christopher Jerry, who was driving me around the island of Efate in his taxi van. As we left the gallery, I noticed that a large sticker with the legend The Sleeping Lion on the van’s dashboard. Christopher explained that this was the nickname of Nguna, his home island, which crouches in the sea just north of Efate. He drove me out of Pango and over the hills north of Port Vila; I could see Nguna in the distance, and had no trouble identifying its curled legs and sunken head.

Jerry looked carefully at all of Patrice Cujo’s paintings, but he was particularly interested in the map of the islands of Maewo and Pentecost. “My wife is from Pentecost,” he explained. “She’s not like ‘Gel Pentecost’, though!” Several years ago a song called ‘Gel Pentecost’ was a hit for one of Vanuatu’s string bands. The song tells the story of a “man Vila”who is married with children, but who has nonetheless fallen in love with a younger woman who emigrated to his city from Pentecost Island. When the girl’s family learn of the affair they send her home, and her inconveniently married lover pines for her.

‘Gel Pentecost’ plays on the distance between Vanuatu’s capital city, with its bars and casino and luxury yachts and shantytowns, and the country’s outer islands, where people live in small villages and grow most of what they eat.

A Pentecost chief named Viraleo Boborenvanua has lately come to symbolise the differences between Port Vila and Vanuatu’s remoter islands. Chief Viraleo is the leader of the Turaga people, who live on Pentecost’s east coast and speak one of Vanuatu’s one hundred and thirty or so indigenous languages. Last year the chief and seven of his followers were arrested and charged with arson and threatening to kill, after a land dispute with some neighbours of the Turaga. The chief and his men were shipped to Port Vila, where they astonished locals by appearing in court wearing only the scanty traditional dress of their island. The chief was charged with disrespecting the judge hearing his case, then released on bail to Port Vila, and told to find a lawyer and a suit.

Chief Viraleo is as hostile to Vanuatu law as he is to urban dress. Like Jimmy Stevens before him, he considers that his authority, as a chief and an expert on ni-Vanuatu kastom, exceeds that of any politician or civil servant in Port Vila. Despite living in exile in the capital, he recently announced the secession of the “Turaga nation” from Vanuatu.

But the clashes between Chief Viraleo and his neighbours show how divisions can occur within as well as between the islands of Melanesia. There has been a tendency for Western commentators on the region to ascribe a common identity to the inhabitants of islands that contain many peoples and languages.

When a secessionist movement on Bougainville battled Papuan troops in the 1990s, many observers talked of a Bougainvillean nation united in its desire to throw off the imperialists of Port Moresby. But Bougainville was divided by the war, with as many islanders opposing as supporting the secessionists, and the popular prophet King Tore 666 raising a militia to fight alongside the Papuans. In Bougainville as elsewhere in Melanesia, the claims of religion, ethnicity, language, and class can divide up the inhabitants of the same island.

Patrice Cujo’s paintings resist the equation of island and identity. They often feature more than one island, and sometimes they portray entire archipelagos, like Torres group in the far north of Vanuatu and the Shepherds in the centre of the country. Beware, the painter seems to be saying, of making easy assumptions. This is Melanesia, after all.

Scott Hamilton

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.