John Hurrell – 19 June, 2017

Because each of us has a private attitude to our own body (ranging from pride, through indifference, to shame) that surfaces when we look in the mirror or think about those we are living with and what they see - a show like this helps us have a rethink, an evaluation of our ‘outer' visible (but unclothed) selves.

Auckland

Works from the Tate Collection

The Body Laid Bare: Masterpieces from Tate

Curated by Emma Chambers and Justin Paton

18 March -16 July 2017

Although this is a touring sampler of traditional works (no moving image, no sound projects, no performance residue) from the Tate Collection that deals with the unclothed human form, extending chronologically from the eighteenth century until now, what we have luckily is mostly a twentieth century contemporary art show.

Only two of the ten rooms focus on eighteenth and nineteenth century masterpieces, and although those galleries are large and crammed with historic works providing fascinating antecedents to current themes such as voyeurism, modesty, feminism and post-colonialism - showcasing what has changed and what has stayed the same - the exhibition really lifts up to another level in the third room, with its three gloriously liberating suites of works on paper from Picasso, Hockney and Bourgeois that surround Rodin’s The Kiss. This quality is sustained in the other galleries from then on.

While in contemporary terms it is a slightly stuffy presentation that avoids anything too disturbing, raw or confrontational (maybe that reflects the Tate collection in general), it is also sensual (Rodin, Spencer, Bonnard, Alma-Tadema, Coplans), humorous (Lucas, Bourgeois, Steer, Bellmer, Sleigh, Currin, Archipenko), tragic (Giacometti, John, Wojnarowicz), haunting (Dijkstra, Sickert, Picasso) and enigmatic (Bacon, Ernst, de Chirico, Brown, Ray) - pitched to a wide Eurocentric audience, but also a foil to this recently added, online, Pacific-flavoured satellite show.

Always tasteful in its choice of what is represented, there are in The Body Laid Bare no erections (though lots of phallic symbols), no graphic coupling, frontal child nudity, bondage, or S&M. As the show progresses through the sequence of ten rooms, you notice various historical developments such as women participating more and more as successful renderers of the nude (particularly male), something they initially were prevented from attempting. You also start to appreciate subtle placements using proximity, such as a small Bacon drawing next to a de Kooning painting (both with rubbery spread legs), or two very different Gaudier-Brzeska sculptures straddling a doorway: one flat, rectangular and a cast relief in plaster, depicting men wrestling; the other a standing woman, carved in stone in the round.

Most of the artists (if now dead) have single works that represent the best of what was achieved out of their life’s work. Sir Stanley Spencer’s contribution though is not characteristic of the religious symbolism and Biblical village narratives he is famous for, but instead is a startlingly candid study of his own unhappy marriage where sex is a doomed attempt to summon up some pleasure. Gorgeously fleshy in its depiction of his own and his wife’s bodies, their long faces paradoxically reveal their underlying misery and mutual dislike. Double nude portrait: the artist and his second wife (1937) is explicit, profoundly honest and extraordinarily moving.

One of the more interesting aspects of Chambers and Paton’s selection is the large Surrealist component, and the high quality of the French and Italian works in the Tate Collection. De Chirico, Man Ray, Ernst, Bellmer, Delvaux, Giacometti; they are all represented by superb examples, and possibly were more greatly appreciated in Sydney (AGNSW, the exhibition’s other port of call) where there is a big interest in Surrealism due to many Australian Surrealist practitioners, than in Auckland.

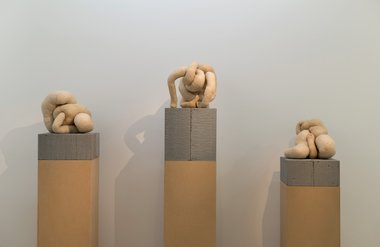

Probably the star of the exhibition overall is Louise Bourgeois, the subject of a large, recently published, very detailed and beautifully illustrated biography by Robert Storr. She has more items than any other artist (eight gouaches, five drypoints, one large sculpture), and rightly so. She is massively adored worldwide and in this show her work has an earthy viscerality and mischievous humour that is very distinctive. Twenty-three dollars is a high price for admission, but her contributions alone provide excellent value.

The Body Laid Bare, despite its vaguely Duchampian title, has no Duchamp, but nevertheless, as a means of focussing on the corporeal, it is a rich and engaging survey. Because each of us has a private attitude to our own body (ranging from pride, through indifference, to shame) that surfaces when we look in the mirror or think about those we are living with and what they see - a show like this helps us have a rethink, an evaluation of our ‘outer’ visible (but unclothed) selves. It leads us perhaps to internal mental narratives that go beyond art - about the maintenance of our (or another’s) health, attractiveness, strength, social compatibility, or self esteem - and whether those body-directed narratives in fact aid or impede our happiness.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

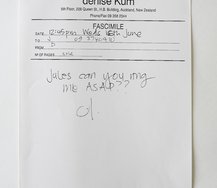

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.