John Hurrell – 4 July, 2017

There is a sense that this publication is an artwork in the contemporary sense, like say Liam Gillick's small publication 'Why Work' of a few years ago. Lye (with Graves) is opening up possibilities for discussion, raising good questions but not really providing answers. Though vague and wish-washy in terms of concrete analysis, it energetically throws down a challenge in a way that no-one else seemed capable of, inviting solutions from any inspired reader.

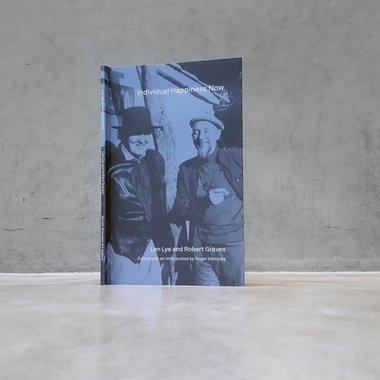

‘Individual Happiness Now’

Introduction by Roger Horrocks

Len Lye and Robert Graves, A definition of Common Purpose

Edited by Roger Horrocks with Paul Brobbel and Sarah Dalle Nogare

Designed by Kalee Jackson

48 pp with b/w illustrations

Published by Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre 2017 RRP $12

It makes a lot of sense that the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery /Len Lye Centre is publishing Len Lye and Robert Grave’s essay, Individual Happiness Now, some 76 years after it was written.

There are three good reasons:

One is the accompanying exhibition at the Govett-Brewster (On an Island, 8 April - 6 August 2017) that celebrates the friendship of Len Lye (1901-1980), Robert Graves (1895- 1985) and Laura Riding (1901 -1991), and the various creative publishing projects they instigated while living together for four months in 1930 in Mallorca in the Balearic Islands. Lye had met the writers Graves and Riding in London in 1927 and they became close friends that kept in touch after he left the island. Riding and Graves were persuaded to come over from London to Mallorca by Gertrude Stein in 1929, and they told her about Lye. They greatly admired the energy and research behind his writing, films and (soon to produce) book covers.

Another is also the very successful symposium of the same name held on 9 June at Auckland University where six highly informative discussions focussed on the Mallorca period, the salient contributions of the three central personalities, and other crucial components like the experimental writer Gertrude Stein and (contextually) the Surrealists. Paul Brobbel (the Len Lye curator) set the scene by elaborating on life on the island, and the wider group of friends, lovers and supportive acquaintances that Lye, Graves and Riding interacted with. Andrew Paul Wood discussed the notion of island utopia, providing many fascinating historic parallels and antecedents, while Linda Tyler drew on Lye’s interest in children’s art, looking closely at the theories of Franz Cižek, Herbert Read, and Marion Richardson.

In the afternoon Ray Spiteri talked about the importance of Nancy Cunard’s Hours Press bookshop in Paris, which normally specialised in Surrealist publications. (Works by Lye and Riding were on sale there even though they insisted they were not Surrealists.) Ann Vickery discussed the work and friendship of Laura Riding and Gertrude Stein, and their respective approaches to reading text and the Surrealist view of the Everyday, while Lisa Samuels examined the Laura Riding poem The Life of the Dead that was published with engraved illustrations by John Aldridge three years after Lye left Mallorca.

Possibility most important reason of all, as suggested by Roger Horrocks in his detailed and erudite introduction, is the relevance of Lye’s ideas (structured and made less ‘eccentric’ and more ‘amenable’ for a wider readership by Graves) to the global political situation in our own time. While much of Horrocks’ contribution is a distillation of pertinent portions of his splendid Lye biography, he also makes comparisons between the world of war-torn Europe of the early 1940s, and the world of 2017. We are living in a time of the ascendancy of Trump and a mandate for Brexit, where there is greater national isolationism, indifference for the wellbeing of the planet, and less tolerance and empathy for the disadvantaged.

The original title of Lye and Grave’s essay was For a Common Purpose, in many ways a far superior heading for a contemporary viewpoint than the (albeit) catchier Individual Happiness Now. While the IHN title seems to effectively be describing the exhilarating euphoria all artists experience when different aspects of a project gel and the finished artwork is perceived by its maker as a great success - with the implication that all individuals can similarly have a creative life - it can also be misinterpreted as a mantra for selfish capitalism; happiness here being synonymous with the individual making a profit, where greed is linked to instant fiscal gratification.

In his early research Lye was inspired by Riding, who in 1937 sent out a mass letter to 400 people about generating solutions to urgent world problems. With her coaxing he began to become interested in politics, putting his ideas in print and becoming acutely aware, for example, of the macho aspects of fascism. He was aware too of the deeply destructive side of capitalism, though he also saw capitalism as encouraging the agency of the individual, a quality he deeply valued. Lye’s interest in politics went up another ratchet when he discovered the writings of JB Priestly, the leftwing social commentator and broadcaster, a couple of years later during the war.

Priestly raised the issue of creative solutions to the world’s ailments, and although he (Priestly) had no answers, Lye started to think very seriously about the subject. He was keen to examine those qualities or rights that brought exuberance or particular satisfaction to an individual’s existence, pleasurable attitudes or life values that were suppressed in totalitarian regimes but which were commonly experienced by ‘free’ artists, and were denied to most.

The caption ‘Individual Happiness Now’ was set up as a foil to the sinister Nazi program of ‘The New Order,’ Lye’s catchy phrase seen as championing positive values worth fighting for, not a default cause of simply fighting against evil or stopping catastrophe. Lye was searching for positive qualities embedded in the democratic process that artists, musicians and other creative thinkers were familiar with, that joyfully exult day to day living, that produce variety and constructively demonstrate the benefits of freedom.

There is a sense that this publication is an artwork in the contemporary sense, like say Liam Gillick‘s small publication Why Work of a few years ago. Lye (with Graves) is opening up possibilities for discussion, raising good questions but not really providing answers. Though vague and wish-washy in terms of concrete analysis, it energetically throws down a challenge in a way that no-one else seemed capable of, inviting solutions from any inspired reader.

My only real disappointment is that this new booklet is too small (being notebook size), but it is typical of course of many current art world publications (like Gillick’s). It is like a pamphlet and so it’s comparatively cheap. However if you look at Lye’s gorgeous book covers in the Govett-Brewster show you’ll see that he regarded the physicality of a book as a crucial component. Wystan Curnow and Roger Horrocks got it right with their 1984 Lye anthology Figures of Motion, as did Curnow and McCann’s Len Lye (2009). The language needs an appropriate setting, be Lye’s text exuberant with ‘zizz’, or more contemplative, analytic and philosophical. Of course Graves greatly mediated Lye’s original text, but nevertheless, a gruntier, more ‘material’ publication (with more surface area extension) for Lye’s ‘global’ thoughts would have been apt.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.