Scott Hamilton – 9 August, 2017

For decades Kawe was kept in a storeroom cupboard; today, though, she dominates the museum's Pacific Lifeways gallery. When I worked at the museum I often saw Kawe stop visitors, in the same way that A'a stopped William Empson in 1932. After reading Marion Melk-Koch's extraordinary essay and the other papers from that strange conference in Switzerland, I want to revisit the museum, and stand in front of Kawe. I want to try to feel the ‘intense radiation' that thrilled and bewildered Melk-Koch.

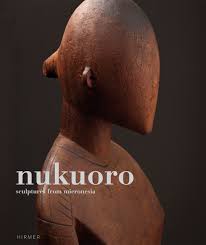

Nukuoro: sculptures from Micronesia,

Edited by Christian Kaufmann and Oliver Wick,

Hirmer Publishers, 2013

In 1932 William Empson met the god A’a at the British Museum. A’a had a smooth, shield-like head and long torso; tiny humanoid figures grew from his wooden flesh. He had been revered on Rurutu Island until the arrival of a new god named Jehovah about 1822. After they had accepted Jehovah’s divinity, islanders presented A’a to the missionaries of the London Missionary Society, who despatched the obsolete god triumphantly to their superiors in the imperial homeland.

Empson begins his poem Homage to the British Museum by wondering at the way a god who once claimed sovereignty over time and space and nature has become an exhibit on a shelf:

There is a supreme god in the ethnological section;

A hollow toad shape, faced with a blank shield.

He needs his belly to include the Pantheon,

Which is inserted through a hole behind.

At the navel, at the points formally stressed, at the organs of sense,

Lice glue themselves, dolls, local deities,

His smooth wood creeps with all the creeds of the world.

But in the second half of his poem Empson turns his consciousness from A’a to the museum that holds him captive:

Attending there let us absorb the cultures of nations

And dissolve into our judgment all their codes.

Then, being clogged with a natural hesitation

(People are continually asking one the way out),

Let us stand here and admit that we have no road.

Being everything, let us admit that is to be something,

Or give ourselves the benefit of the doubt

The poet stands and gazes about the museum, trying to assimilate its miscellaneous gods and cultures. But he is distracted by other visitors, who have gotten disorientated, and have had to ask him for directions to the building’s exit.

Empson suddenly understands that there is no ‘road’ through the museum, and no real ‘exit’ from the building. The museum’s curators have displayed thousands of objects gathered from around the world by emissaries of British imperialism. Taken from the places and deprived of the uses that gave them meaning, gods like A’a have become mere exhibits.

But by relativising all the creeds of the world, the museum’s makers have deprived themselves of any overarching, cohering perspective.

When David Hume upset British society by professing scepticism about Christianity in the middle of the eighteenth century, he defended himself by pointing to the gods of the indigenous societies that the British were beginning to colonise. How, Hume asked, can we believe in our god, when we see the mortality of so many other gods? Why should our truths be special? In much the same way, William Empson seems to be asking, in 1932, why the values professed by British imperialism - Christianity, capitalism, industry, British law, empirical inquiry - should considered any less fragile and mortal than A’a.

‘There IS no way out of the museum’, Brian Appleyard exclaims, in a commentary on Empson’s poem that he published in the New Statesman in 2003, to mark the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the British Museum. Appleyard recognises that ‘seriousness oozes out of the smooth wood’ of A’a, but thinks that, with the faith that sustains him gone, the god has ‘no road’ and ‘no home to go to’. And nor, Appleyard observes, do we.

***

Graham Fletcher’s paintings show the artefacts of indigenous peoples on display in the interiors and yards of Western homes. The artefacts in his paintings are typically, though not always, from the Pacific; his homes are often in the ‘mid-century modernist’ style associated with American architects like Frank Lloyd Wright. Like A’a, the artefacts that Fletcher paints have been ripped from the settings that gave them power. A carved pole that perhaps once guarded a spirit house on the Sepik might decorate the space between sofas; a culture hero might be found squatting on a ledge, staring through sliding doors at a lush yet tidy lawn.

Several of Fletcher’s paintings are on display at Pah Homestead, in an exhibition on the first floor called Situation Rooms, part of a suite of exhibitions on the first floor with the umbrella title In Residence. The largest of the paintings shows a dark-wooded figure with a straight back and a flaccid penis standing beside a bookcase in a lounge room.

The homes that Fletcher paints are themselves artefacts. They recalls the 1950s and ‘60s, and a zeitgeist of prosperity and complacency. The bookcases and artefacts in Fletcher’s homes remind us that, for the American upper classes in the post-war decades, high culture could be, as much as a late model car or a swimming pool, a symbol of status. In ‘Why Bother?’, his magisterially grumpy survey of America’s cultural decline, Jonathan Franzen noted how, in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Time magazine regularly put ‘serious’ writers like John Cheever and James Baldwin on its covers, and how an education in the arts was seen as a necessary prerequisite for being a civilised member of the bourgeoisie.

In the 1960s Nelson Rockefeller, the captain of American capitalism and a senior Republican politician, could devote a portion of his hours to collecting and exhibiting avant-garde art, and encourage his son to go to New Guinea to photograph and collect indigenous artefacts. By the end of the twentieth century, though, high culture and intellectual inquiry had lost their cultural cache, and money had, in Franzen’s unhappy phrase, become ‘the yardstick of all value’. Modernist architecture had been replaced by tasteless neo-classicism and gaudy postmodern eclecticism, and the at least outwardly civilised Rockefellers had been usurped, as symbols of American capitalism, by the determinedly vulgar Trump family. In the epoch of neoliberalism American capitalism, like British imperialism before it, has lost faith in its civilising mission.

The yards and rooms of Fletcher’s paintings are deserted. Without people, his elegant lawns and lounges lose their function, their identity. They have the pathos, the absurdity of cars abandoned in the middle of the road in a post-apocalyptic movie.

Like William Empson’s poem, Fletcher’s paintings show us a world that has become uncentred, relativised. The British Museum and the modernist homes of mid-century art collectors were supposed to order and explain the objects they contained. Artefacts like A’a were supposed to be picturesque and heuristic details, subordinated to a larger scheme. But the categories and narratives of the appropriators have evaporated. The museum’s visitors are lost amidst a chaos of inexplicable artefacts: the owners of Fletcher’s homes have withdrawn from their impeccable and inscrutable interiors.

The late Mark Fisher talked about the ‘lost future’ of the modern era. Since the 1970s, Fisher argued, the modern dream of a more prosperous and progressive world has evaporated, making many of us ‘nostalgic for the future’. The ‘lost future’ of modernity beleaguers the abandoned houses of Fletcher’s paintings in the same way that the lost religion of Rurutu haunts A’a.

***

In the last two lines of ‘Homage to the British Museum’, Empson shifts focus again, and makes a proposal to his readers:

Let us offer a pinch of dust to this God,

And grant his reign over the entire building.

Empson’s most famous book is called Seven Types of Ambiguity, and the last lines of his poem can, like all his words, be interpreted in multiple ways. But a reader might plausibly see him turning away, in boredom or terror or disgust, from the relativised world he has found in the British Museum, and proposing the reconsecration of A’a. By acknowledging the exhibit as a god, and letting him reign over the entire building, and therefore the entire universe, Empson might find a road, and a home.

But how might Empson reanimate, reconsecrate A’a? Is it possible to turn an exhibit back into a god? Could a European scholar like Empson become the adept of an indigenous religion?

The British Museum embodies the Enlightenment ideal of the objective cataloguing and study of the world. The missionaries who landed on islands like Rurutu may have intervened aggressively in local life, but the anthropologists and linguists who followed them, in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, attempted to observe rather than influence the societies they encountered.

And yet not all scholars could remain detached. Reo Fortune travelled to the New Guinea island of Dobu to study religion, and soon became obsessed with local gods and magic. Fortune’s book Sorcerers of Dobu, which was published the year that Empson wrote ‘Homage to the British Museum’, collects poisons and curses, and follows ghosts and spectres over reefs and through jungles. When Fortune took up a post in anthropology at Cambridge University, he brought the religion he had learned in Dobu with him. Former colleagues of Fortune remember him rising during a seminar to chant a curse at a visiting academic he disliked; they recall how he explained a fire in a lecture room as an experiment in Melanesian magic.

The German anthropologist Gerd Koch also moved from the study to the practice of Pacific religion. Koch landed on the Tuvaluan island of Niutao in 1960 with a tape recorder, looking for old men and women who remembered the storm-quelling and fish-finding songs of the pre-Christian era. Koch was soon recording Saipele, the island’s master carpenter and one of its last pagans. Saipele initiated Koch into his religion, naming the turtle as the anthropologist’s totemic animal. Koch left Niutao after a year, but kept to the tenets Saipele had taught him for the rest of his life.

Reo Fortune and Gerd Koch were converted by the living practitioners of indigenous religions. But can a scholar succumb to a religion that has no indigenous believers left, a religion that exists only in old texts and in a few objects, like the poignant masterpiece William Empson encountered at the British Museum?

***

Nukuoro is a broken circle of forty-eight islets set on coral five hundred kilometres south of Pohnpei, the capital island of the Federated States of Micronesia. Although they live thousands of kilometres north and west of the Polynesian heartland of Samoa and Tonga, the people of Nukuoro tell stories about Maui and Tangaroa and call the sun and moon ra and masina. Like the other scattered peoples of Outlier Polynesia they have preserved their culture for centuries, despite being surrounded by larger Melanesian and Micronesian societies.

When the first Europeans visited Nukuoro in 1805, the island had about five hundred inhabitants, who lived by fishing and gardening.

There were two types of deity on Nukuoro. Aitu tanata, like the goddess Te Haukula and the god Wawe, were the spiritual residue of great ancestors; aitu tupuna, like Toro Etai, the Lord of the Sea, and Te Ariki ku te Rani, the Lord of the Sky, were self-created. Religion was a practical, communal matter. Deities had to be propitiated, or else fruit would rot before it ripened, and fish would flee the lagoon. In long rectangular temples the Nukuoroans gathered before rows of carved god-vessels they called tino aitu. As their priests lay food before the tino aitu, garlanded them with flowers, and crowned them with leaves, the Nukuoroans sang and danced to the gods’ glory.

By the time a trading station was set up on Nukuoro in 1873 the old religion was ailing. Islanders salvaged tino aitu from caved-in temples, and sold them to traders, who in turn delivered them to museums in Europe and Auckland.

In 2009 dozens of curators and anthropologists gathered at a museum near the Swiss city of Basel. They were joined by fifteen tino aitu carved on Nukuoro in the nineteenth century.

The tino aitu that gathered in Switzerland in 2009 looked very similar. All had ovoid heads that tapered steeply to chins. Their faces were either featureless, or else had faint scratches that stood in for eyes and noses. Their torsos sloped down to short legs.

The simplified forms and smooth surfaces of Nukuoro carvings fascinated European modernists. Alberto Giacometti’s famous sculpture Hands Holding the Void was a response to a Nukuoro carving in Paris’ Musee de l’Homme; Henry Moore was preoccupied by a tino aitu he found in the British Museum.

A book of papers, photographs, maps, and old ethnographic reports was issued to commemorate the conference of Nukuoro scholars. In the paper that she contributed to the conference and the book, Gerd Koch’s widow, Marion Melk-Koch, explains how, when the tino aitu arrived in Switzerland from their various museum homes, something strange began to happen. The carvings seemed, to Melk-Koch, to come to life; it was as though they were ‘charging’ one another. Standing between two tino aitu, Melk-Koch felt an ‘incredible radiation’: it was as though the old gods of Nukuoro had ‘regained their power’ by being reunited.

The tone of Melk-Koch’s paper, which she called ‘Objects from an Outside World - Walking In and Out’, alternates between the analytic and the awestruck. When she ponders possible connections between the Nukuoro carvings and the wider canon of Polynesian art, and wonders when the island was first settled, Melk-Koch’s language is restrained, even austere; at other times, though, it becomes poetic, rhapsodic. Looking at a satellite photograph of Nukuoro, she decides that island resembles an ‘egg being inseminated’. ‘Do they have a soul?’ Melk-Koch asks of the tino aitu, after standing in their ‘radiation’.

Many of the other contributors to the conference seem to have struggled to maintain the conventions of scholarly detachment, and resist the power of the objects arrayed about them. It is hard to read the papers of Marion Melk-Koch and her colleagues without feeling that these European curators and anthropologists have somehow taken the place of the indigenous priests who once protected and revered the tino aitu of Nukuoro.

The scholars long to understand the carvings they adore. They pore over the textual remains of early traders on the island, annotate old photographs, stare again and again at the carvings. The longing becomes extreme in Christina Hellmich’s paper ‘A Tino Aitu figure below the surface’, which features blown-up x-rays of a carving’s torso and armpit. Hellmich detects erosion-fissures in the wood, and openings gnawed by tropical insects. Her images feel at once voyeuristic and reverential, like Bonnard’s nude paintings of his wife or Bernini’s sculpture of an orgasming St Theresa.

Despite all their labours, the scholars who gathered in Switzerland were unable to explain the essential mystery of the Nukuoro carvings, the mystery that Bernard De Grunne calls ‘the fascinating problem of the appearance on such a small island of such a great artistic tradition’. Why, Marion Melk-Koch asks with a mixture of awe and frustration, ‘do these figures look like they are not from this planet?’ Did numinous experience of the statues begin at the point where analysis was exhausted?

***

The largest and most famous of all the Nukuoro carvings stands not in Europe but at the Auckland War Memorial Museum. The carving has the same ovoid head and featureless face as its kin in Europe, but large breasts hang from its otherwise featureless torso. The tino aitu in Auckland is known as Kawe, after the wrecker of harvests and canoes that the Nukuoroans tried to placate with coconuts and fish and dance.

For decades Kawe was kept in a storeroom cupboard; today, though, she dominates the museum’s Pacific Lifeways gallery. When I worked at the museum I often saw Kawe stop visitors, in the same way that A’a stopped William Empson in 1932. After reading Marion Melk-Koch’s extraordinary essay and the other papers from that strange conference in Switzerland, I want to revisit the museum, and stand in front of Kawe. I want to try to feel the ‘intense radiation’ that thrilled and bewildered Melk-Koch.

Scott Hamilton

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.