John Hurrell – 11 March, 2020

Walking through you get a distinct physical experience from the installation of paintings limited to each period, a flavour particular to that immersive architectural space in the sequence. This provides a refreshing physical and mental experience, looking at Henderson's different thematic preoccupations that sometimes are ambiguous: 'constructivist' abstractions for example doubling as clothed male Arab figures, or clouds in sky doubling as blurry (vague with no detail) self-portraits.

Auckland

Louise Henderson

From Life

Curated by Julia Waite, Felicity Milburn and Lara Strongman

2 November 2019 - 8 March 2020

In June it opens at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu

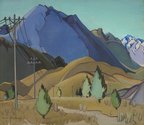

In this travelling Louise Henderson (1902 -1994) retrospective—a partnership between the main art institutions of Auckland and Christchurch—we see a focussed examination of the life work of the well-travelled French/New Zealand painter, with her many interests and styles (but mainly semi-cubist portraits, still-lives and landscapes) divided into seven linked thematic sections.

Born and raised in France, Henderson married a New Zealander and came to Christchurch in 1926 (getting a job in teaching embroidery and design at the Canterbury School of Art, and then befriending the members of the (comparatively) experimental coterie, The Group), bringing a then rare European sensibility to the three New Zealand cities she lived and worked in. They moved to Wellington in 1942 where she continued teaching and painting. In 1950 they moved to Auckland.

In the early fifties Henderson studied with the cubist painter, Jean Metzinger, in Paris and then with husband Hubert travelled for several years throughout the Middle East, observing its people, bright light and geometric architecture. They returned to Auckland and after more teaching and some commissions, Louise had a research trip to Europe and the UK in the mid-sixties. When she returned to New Zealand, she was struck by its distinctive landscape and vegetation—enthusiastic about it as subject matter for painting.

Within the exhibition’s organisation, each demarcated stylistic division is very clear (see images), and often formally tight, so walking through you get a distinct physical experience from the installation of paintings limited to each period, a flavour particular to that immersive architectural space in the sequence.

This provides a refreshing physical and mental experience, looking at her different thematic preoccupations that sometimes are ambiguous: ‘constructivist’ abstractions for example doubling as clothed male Arab figures, or clouds in sky doubling as blurry (vague with no detail) self-portraits.

The scale of Three Women of Jerusalem (1959) shows us Henderson‘s determination to be taken seriously as a woman artist who can strut her stuff with male colleagues (like Milan Mrkusich) who use large canvases. The work is confident, muscular and rhythmic—a big leap in her formal ambitions that leads eventually to the line of seasonal works at the end of the exhibition. Its synthetic cubist flatness and nuanced placement of elements indicate she was more beholden to Gris than Picasso (despite being a nod to his Three Harlequins, 1921), a logical product perhaps of being taught by Jean Metzinger in the early fifties.

Although in her early works Henderson might be seen as a bit of a magpie (especially with friends like Rita Angus, or teachers like John Weeks), with the more brusherly (less hard-edged shaped) works she appears more avant-garde—influenced by Abstract Expressionism in the early sixties, though still linked to the palpable world (its weather conditions, landforms, vegetation and light) as content. Here her work becomes looser and less geometric—more atmospheric, though rarely totally abstract.

This is a fascinating exhibition, and a pleasure to wander around, circumnavigating back and forth, making comparisons and links. As a body of work though, I’m not sure it successfully argues for the re-evaluation of Henderson‘s status that the curators advocate. Henderson’s career is too fragmented, with sections of stopping and starting—spontaneous gains and sliding reversals—and gaps, that result in an insufficient number of resolved ‘mature’ works to make any sustained art historical impact.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

In a recent phone conversation, Julia Morison suggested to me that the installation of this Henderson exhibition is far superior ...

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 8:58 p.m. 3 July, 2020 #

In a recent phone conversation, Julia Morison suggested to me that the installation of this Henderson exhibition is far superior in Christchurch, the spatial design for the show there being with the paintings fitted around the concepts of the project--not around the given gallery floor plan. (Apparently warm lighting also greatly enhances the works.) CAG's exhibitions team has a formidable national reputation, based on work they have done with solo art shows like those of Fiona Pardington, Ann Shelton and others. Personally I think AAG did a fine job with Henderson, and they certainly did well with the current 'Civilisation Photography Now' show. Any other opinions from observant readers?

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.