Peter Dornauf – 26 November, 2020

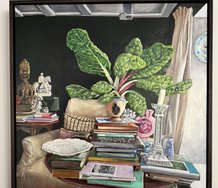

But where is the man himself? Can he be found in his current show at Aesthete Gallery, one that presents a kind of smorgasbord or quick sampling retrospective of stuff spanning three decades, from 1992 to 2020? What such an exhibition demonstrates is the artist's ubiquitous magpie proclivities.

I think it was Harry Secombe who, in commenting once on fellow Goon, Peter Sellers, said that the man didn’t have a voice of his own so taken over was he by the voices of others. The wonderful mimic hid behind multiple masks which eventually completely subsumed the real man. Which brings me to Dick Frizzell and his current publication, Me, According to the History of Art. Frizzell here does the ultimate mimicry job in re-creating the works of the ‘masters’ down the ages, (not a single women artist is referenced).

The question one immediately wants to ask is why would anyone want to do such a thing? Is this Frizzell simply upping the ante, cocking a snook at Marvel Comics who took him to task over his imagery ‘theft’ of their works? (Interestingly, no one filed a suit against Roy Lichtenstein, although the original illustrators did make grumbling noises.)

Strangely, in the thick tome (Massey University Press), art history seems to have stopped for Frizzell around the 1960s—apart from one or two exceptions—since his appropriations/copies come to an end with a Warhol piece. Nothing of interest enough seems to have happened since then, according to the man. Nothing worth copying anyway, other than Peter Halley and Sandro Chia.

The book simply underscores that Frizzell is the consummate mimic. He’s good at it and that’s what it is.

But where is the man himself? Can he be found in his current show at Aesthete Gallery, one that presents a kind of smorgasbord or quick sampling retrospective of stuff spanning three decades, from 1992 to 2020? What such an exhibition demonstrates is the artist’s ubiquitous magpie proclivities.

A new work, print on paper, depicts a portrait of McCahon, Colin Compared (2020)—head and shoulders, in slightly stylized fashion—juxtaposed against his lamp, straight out of Crucifixion with Lamp (1947). It has a singular quality and a simple beauty, both borrowed images (one from the mentioned McCahon painting, the other from a photograph) which because of their stylised treatment, look as if they belong together. Frizzell is the supreme bricoleur.

The oldest work in the show, Vorticist Tiki Rug study (1992), has the appearance of a preparatory sketch to do with his controversial series that took the hei-tiki and translated it into a series of reworked images in styles taken from European modernism. In Tainui circles it created a lot of anger. A scheduled show of his at the Waikato Museum was cancelled at the time. Shades of Charlie Hebdo—in that religious/spiritual issues were involved—though Frizzell wasn’t being satirical or being provocative, more playing with modernist art history.

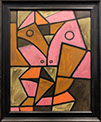

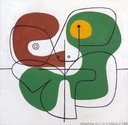

This exhibition at Aesthete contains a number of painted works in that mode which suggests that the artist hasn’t done with that subject. A recent painting (oil on canvas), PK-TR, sees Frizzell continue to blend abstraction with the tiki motif. The man is still in love with cubism. Another, from a decade earlier, International Style Tiki 11 (2020), calls on Miro and his biomorphics. They are all cleverly done, as is the nod to Picasso in Pascoid #13 (2013).

But is all of this performance and duplication, postmodern leverage—or evidence of a man simply taken over by his many masks? When we are presented with I’m Here for the Monkey (2016), a replica of the Phantom throwing a clichéd punch at a felon, or any of the other examples of Marvel comic-strip art represented in the show, it does raise the above question, irrespective of how well the artist pulls off the trick.

And then there is the landscape series, works which went regional, capturing quintessential rural New Zealand scenes, as in Water Tank and Pumping Shed (2011), but deliberately painted in a faux naïve art society painting style. The man can paint; no question. And he can even do ‘bad painting’ well, but where is the artist himself?

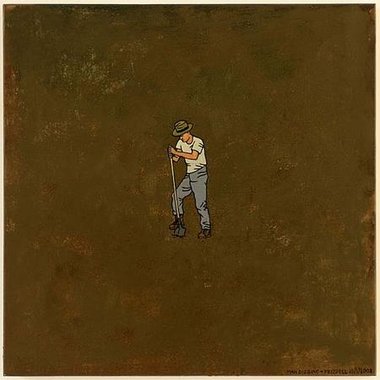

Perhaps the answer comes closest in a small series of works that present singular figures, doing very ordinary things, against a large minimalist background, such as a man creeating a hole with a shovel, Man Digging (2008), a girl nursing a cat, Girl with Cat (2008), or a pair of common pliers like Vice Grips (2018). Is it here we find the artist being himself, without tricks, contrivance or stylistic disguises taken from elsewhere? Is this the real Frizzell, rather than Frizzell doing Warhol, or Picasso or Paul Klee, or Jack Kirby, Frank Miller, Steve Ditko and a host of other comic book scribblers?

The other question is: does all this really matter? Maybe what Frizzell has done best is democratise art: cut out the pretension, the posturing, the self-importance. And for all that, he has become in this country, the people’s artist. Low subject becomes high art, while high art becomes low subject, in a convoluted way.

The Aesthete exhibition provides a unique opportunity to see the man at work over an extended period of time, and to enjoy the impersonations, the simulation, the clever adaptions and modifications, with a good dollop of nostalgia thrown into the mix.

Peter Dornauf

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.