Peter Ireland – 30 November, 2011

Maybe in his enmeshing of mythological figures in a late-Modernist abstract web of lines and patterns he's suggesting they're more than embodiments of outdated beliefs, datable images in art history or epitomes of figure drawing? History's not just an inert then up against a livelier now: it's a whole pile of mixed-up shit that's endlessly engaging and illuminating.

In Te Papa’s current Collecting Contemporary show there’s a wall label that goes like this: The term decorative arts describes artistic works that are created for use and decoration. These include ceramics, glassware, jewellery, metalwork, furniture, interior design, fashion and textiles. Following the Renaissance, decorative art and fine art were considered to be quite separate, but today there is a blurring of the boundaries between them. This is particularly true when objects such as ceramics or jewellery are made primarily to explore ideas. These ideas may be about functionality itself, process, aesthetics or wider concerns like environmental sustainability.

Immediately to the left of this label is a Perspex-topped plinth containing a metre-tall ceramic piece by Paul Maseyk, Same shit different country - memories of Montana, acquired by the Museum in 2008. The first impression is of an elegantly-formed, highly decorated antique Greek vessel, something Sir William Hamilton might have picked up for his famous collection, formed when he was British Ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples for thirty-six years in the 18th century. Pull the other one, you might say, but the connection’s not too far-fetched, as Maseyk does have a copy of the sumptuous c2004 reprint of the 1766 Collection of Antiquities from the Cabinet of Sir William Hamilton.

Hamilton’s well-known for a number of reasons. In this Facebook culture, it’s probably mostly for his wife’s affair with Lord Nelson. He seems an interesting guy though: he’s said to have trained his pet monkey to examine the classical vases with a magnifying glass to send up the scholarly interests of the antiquarians, and in Maseyk’s practice there’s certainly some monkeying around with classical models. Hamilton would probably approve, because his greatest and quite singular achievement was to collect the stuff not from any primary interest in archeology or art but to provide models for contemporary artists. One of them, Josiah Wedgwood, derived the inspiration for his signature neo-classic ware almost entirely from the 1766 publication.

Wedgwood’s a pivotal figure here. The question “Is he an artist or a craftsman?” was a new one in his day, and the very question’s needing to be asked points to a distinction between “fine art” and “useful art” that has significant ramifications to this day. Despite the earlier invention of printing and other technological developments, the now-common distinction between art and craft simply wasn’t necessary before the Industrial Revolution took production to a new plane in the 18th century. The same century’s mania for classification ranked art practice in a hierarchy that pretty much still pertains: painting and sculpture at the top and stuff like jewelry and ceramics at the bottom. And even recent blatherings in these parts about bi and multi-culturalism haven’t managed to materially dislodge this hierarchy to make room for artistic productions such as body adornment and weaving. Making room would be a good start, but on current evidence it’s going to take a long time before something like the local tradition of korowai, for instance, is recognized for what it is. In this case, current evidence could be the immense gap between what is represented by the content of the recently re-opened Auckland Art Gallery and the content of the recent Te Papa Press publication edited by senior curator Awhina Tamarapa Whatu Kakahu: Maori Cloaks? The time will come when this gap will close and the old hierarchy upended, but why do we have to wait?

For all Postmodernism’s promise of plurality, a recognition that all positions are historically and culturally conditioned, and its theoretical commitment to re-examining all bases, the Modernist mind-set around this two-hundred year-old hierarchy remains firmly in place. Kiwis pride themselves on their innovation - and there’s plenty of evidence for that, after all - but why can’t that can do/go get attitude apply to thinking?

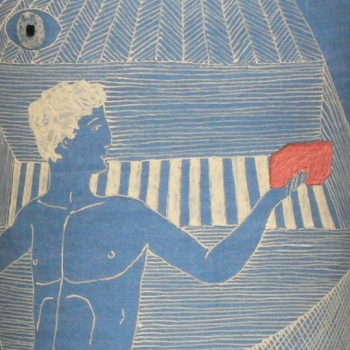

In Maseyk’s show there’s more than a playful nod in the direction of Wedgwood’s ubiquitous blue and white ware. In his richly decorated surfaces (“decorated surfaces”: what a Modernist indictment!) there are references to figures from antique Greek vases: Venus, Aphrodite, Hercules et al, but they’re combined with a system of abstract, geometric drawing the artist’s invented having echoes of Op Art, particularly the perception-scrambling imagery of Bridget Riley. In employing this stuff here, maybe Maseyk’s strategy is to scramble the iron grip of those hierarchic categories which automatically disadvantage practices such as his own in being taken seriously. Maybe in his enmeshing these mythological figures in a late-Modernist abstract web of lines and patterns he’s suggesting they’re more than embodiments of outdated beliefs, datable images in art history or epitomes of figure drawing? History’s not just an inert then up against a livelier now: it’s a whole pile of mixed-up shit that’s endlessly engaging and illuminating.

In this culture - but probably less so for the Greek - an example of this mixed-up shit could be that endlessly engaging and illuminating subject usually called pornography. Modernism tended to be sniffily puritanical about anything sexual (unless in forms of heavy metaphor a la Meret Oppenheim or Hans Bellmer), but Maseyk re-connects with the Dionysian spirit running erratically through Western culture, typically updating it with wit and a dangerous playfulness, undermining the prim categories of standard art history and questioning the assumptions of society’s moral guardians. The eroticism of classic Greek decoration has been embodied by Maseyk in the objects themselves: the tits and cocks formerly pictured have here become features of the forms.

In a series of five squat cylindrical objects entitled Disco Paul, he cocks a snook at the sort of cool macho style idealized in the figure of James Bond, Maseyk’s cool being a kind of sleazy desperation that’s as comic as it is creepily true to life. Notions of the classic and neo-classic come with their own assumptions of cool, and within the seemingly classic forms of his objects Maseyk creates a personal mayhem that, being at odds with the forms, sets up a dynamic that’s both challenging and stimulating.

Nothing is sacred. “Serious” ceramics can be awfully po-faced about surface treatments: everything from the driest of matts to the wettest of glazes - seldom mixed together. Maseyk mocks this milieu of good taste by using bright colours, usually red and gold, using car paint baked on in the local repair shop. The famous “red vase” tradition is here referenced and revived with a vividness recalling fresh blood. In his blurring of boundaries as suggested by the Te Papa label Maseyk doesn’t simply “explore ideas”, he goes for the jugular.

Peter Ireland

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.