Peter Ireland – 8 November, 2013

There is no doubt that PTWTM has superb production values. But then, so did the Nuremberg rallies. We're back to the old Scholastic distinction between appearance and substance, but if anyone's talking about any kind of excellence, it's still a distinction with currency. Getting a stamp on your hand for achievement might work in Year One, but post-Year Thirteen in a culture with any depth it seems reasonable to expect a little more than just taking part.

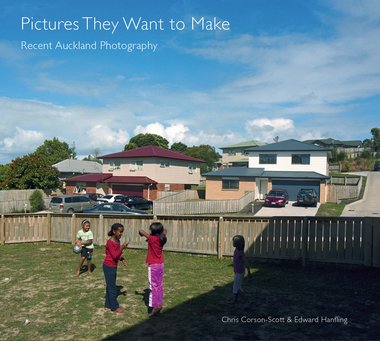

Pictures They Want to Make: Recent Auckland Photography

Edited by Chris Corson-Scott and Edward Hanfling

Foreword by Ron Brownson

Hardcover, 176 pp, text and coloured illustrations

Published by PhotoForum Inc., Auckland, 2013

RRP $59.95

The notion of the ghetto is predicated on a “difference from” as is the consequent attempt to preserve the separate identity involved by living within a physical border, like Polish Jews, or an intellectual one, like, say, the Mormons. In time, such separations become so ritualized that they themselves form a central element of that identity. The fact that subsequent history may have dissolved the reasons for the ghetto’s original construction is often of little interest to its inhabitants, and indeed, any suggestion that it might have is perceived as hostility and, as such, a further threat to the encircled identity. As psychologists know, victimhood can be a great comfort. But in what we call the real world, the warmth generated by such comfort can be a fatal attraction. It’s what Karl Stead was talking about when he referred to “New Zealand’s cosy literary parish”.

In 1974 a loosely constructed but philosophically focused entity called PhotoForum Inc was set up by two photography lecturers at Auckland’s Elam art school: John B Turner and the late Tom Hutchins. Their aim seemed fivefold: to provide an intellectual forum for practising photographers, an umbrella under which to legitimise and show their work, to issue publications, to stimulate historical research and to raise the profile of the medium to the point of wide acceptance as an art form.

In the early 1970s here this acceptance was pretty much confined to the photographers themselves, and then more an earnest hope than a demonstrable achievement. On the one hand you had the old Pictorialist guard of the camera clubs, still card-carrying members of the George Chance fan club, and on the other, an emerging generation of baby-boomers, better educated, determined to be progressive, and eager as to sign up to the Edward Weston fan club. There were some anomalies - a bit weird but historically telling - such as the case of Brian Brake whose work had star quality locally not because of the imagery so much as for the fact he’d “made it” overseas, thus reassuring an insecure provincial culture that it was not quite as insignificant as it felt. Outside this tight circle of actual practitioners the wider New Zealand public held firm its belief that photographs, being made by a machine, could not possibly qualify as art. Where this left concert pianists with their Schumann and Chopin one can only wonder.

Over the ensuing forty years this situation has changed significantly, and PhotoForum’s positive contribution to this is out of all proportion to its size and organization, constituting an unarguable triumph of aims achieved. Most of the credit for this must go to John B Turner’s enduring vision, determination and drive. Of course, over the years many other individuals have put their shoulders to the wheel - and continue to do so - but without him PhotoForum would not have lasted more than about eighteen months.

The cautionary truism “be careful what you wish for” may, in retrospect, have been a wise motto for PhotoForum. At its foundation it was basically a bunch of photographic amateurs - in all senses of the word - dedicated to professionalizing the object of their love. This sense of mission resembled a military campaign in many respects, albeit more often a Dad’s Army than a Wehrmacht: instilling endurance, marshalling the troops, inspiring loyalty, identifying specific targets, re-assessing tactics and mythologizing small triumphs. As in any war situation there was not much time for niceties - sizing up the costs of winning is an accounting practice reserved for peace-time, as are the implications of achieving the objective, which tend to be overlooked in the heat of battle. The moral aspects of, say, the destruction of Monte Cassino’s abbey or the fire-bombing of Dresden have been, necessarily, issues for post-war concern. The force of achieving the objective tends to shove aside reflective consideration of more fundamental issues.

It’s the character of amateurism to focus more on action than reflection - a pseudo-Cartesian equivalent, “I do, therefore I am”. One of Hunter S Thompson’s harsher comments goes like this: “Photographers just run around sucking up anything they can focus on and don’t talk much about what they’re doing. Photographers don’t participate in the story. They all can act, but very few of them think”. The situation’s perhaps a casualty of the “decisive moment” syndrome; being alert to and being capable of capturing the instant rather than reflecting on the context. In a special edition of Art Collector magazine produced for the 2013 Auckland Art Fair there’s a short article about Anne Noble and she’s quoted as saying “If we are truly becoming people of the screen and formed by visual images, we have to understand the sources and how that forms and shapes us.” In short, the task of intelligence.

But the unthinking situation goes deeper, further back in time. Here in the 1970s it was overwhelmingly all about photographers talking to themselves: (a) they needed the conversation and (b) no one else was listening. The agenda was three-fold: their needs, their desires, their ambitions. John Szarkowski’s simplistic, late ‘70s distinction between mirrors and windows was a crude rule of thumb when it came to illuminating American photography post-1960 (1), but it has some currency in describing the self-referential outlook of photographers in New Zealand then, and, if Pictures They Want to Make is anything to go by, now. No one involved in this project seems to have turned away from the mirror long enough to look out of the window and ask, are these Pictures Non-Photographers Want to See? Or even, are these Pictures That Needed to be Made? It’s as if at the end of the Thirty Years’ War the soldiers of the victorious armies celebrated by shooting themselves in the feet.

Admittedly, it would take not only a self-critical gene to resist the opportunity to be included in book so lavishly produced; it would take a genetic disposition to complete self-control. It’s almost twenty years since a publication appeared under the auspices of PhotoForum encompassing photographers from the Auckland region: Open the Shutter: Auckland Photographers Now, of 1994. It included 40 photographers but consisted of only 23 pages and 23 images. PTWTM, by contrast, includes just 12 photographers but sports 176 pages and 102 images. Its fifteen portfolios vary in character: some have a consistency of subject, such as Fiona Amundsen’s, Ian Macdonald’s and Talia Smith’s (Bruce Connew’s has a consistency of title); some are compilations of work over a decade, such as Mark Adams’, Edith Amituanai’s and Haru Sameshima’s; most of the photographs are being published for the first time, but many have been seen before, and some perhaps too often: Amituanai’s White Sunday and Geoffrey Short’s explosions, for instance.

Apart from offering the various photographers a platform it’s hard to know what PTWTM is about. As the authors admit, the “Auckland” net is more holes than string, and why should some sort of regionalist focus matter anyway, taking heed of Jackson Pollock’s remarking on the absurdity of an “American mathematics”. Of course, there’s probably more photography produced in the Auckland region, but if we’re talking sheer volume it might be more to the point discussing hydro-electricity along the Waikato River. And, oddly, PTWTM‘s content isn’t about variety either - the more modest Open the Shutter: Auckland Photographers Now demonstrated a much more diverse range of practice, which in the two decades since has expanded rather than contracting. Upon repeated examination it becomes clearer that what this book is about is the persistence of an amateur outlook formed - however inescapably - in the 1970s, but which has very little reason to exist in the second decade of the 21st century.

It’s instructive to compare PTWTM with the Hannah Holm-inspired publication of 2006 Contemporary New Zealand Photographers (2). On the face of it they have similar aims; to present to a wider public a range of contemporary photographic imagery. On closer examination, however, they’re very different animals. In comparison to PTWTM‘s dozen Aucklanders CNZP included 20 photographers from across the country, contained 183 pages to the other’s 176, and 179 images to its 102. Constituting something of a photographic A-Team, Adams, Amituanai and Amundsen are common to both books.

Statistics can illuminate only so much. The significant difference between CNZP and PTWTM is that the former was edited by a professional curator who is not a photographer with about two decades of respected and proven experience in presenting art to a wider public. The title page of PTWTM credits two people with the editing - admittedly, one of whom, also not a photographer, is known as a curator and art writer - but the acknowledgements page makes it clear that the project is the baby of the other editor, one of the photographers included, someone whose work has not been seen in any quantity anywhere until this book’s publication. Well, you could say, is this a case of CNZP‘s art world gate-keeper up against PTWTM‘s enthusiastic rookie demonstrating the kind of “innovation” brand-makers from the Prime Minister up currently seem so fixated on? You could say too that the proof of the pudding is in the eating. CNZP was driven by an intention to inform the public: PTWTM is driven by the needs of the photographers to promote their work. The former was characterized by a series of critical filters that the latter so conspicuously lacks. It’s reportage as against the classifieds.

Another significant difference is the CNZP editor commissioned essays from a range of experienced writers on the medium for each of the photographers included, herself providing the piece on Marie Shannon’s work. All of PTWTM‘s texts are not only written by the two editors - neither of whom has any track record writing about the medium - but written jointly. Sociologically again, collaboration is a lovely idea, but in art (unless you’re rare birds like Culbert and Hotere) it rarely works because art-making isn’t about any sort of consensus, it’s about individual achievement. The truism about camels, horses and committees still says it all.

PTWTM‘s lack of focus in what “Auckland” might mean, a similar lack around the book‘s raison d’etre, and within most of the contributed portfolios is also a feature of the writing. It seems to be aimed at a general audience - a refreshing admission, at least, that non-photographers exist - but ends up a mish-mash of notions that mostly had their day in ‘80s debates, and of ideas that are conspicuously undigested.

To take a random example: the opening of the essay accompanying Harvey Benge’s portfolio states: One of the problems when talking about photography as art is the difficulty of separating the content of photographs - the reality at which the camera was pointed - from the photographs themselves. There are three assumptions in this statement: first, that it’s possible to talk about photography as art without a lot of qualification and explanation. Second, that any photographic subject matter can be described, simplistically, as the reality at which the camera was pointed as if it were simply a given. Third, what the authors claim to be a particular difficulty in photography is actually a difficulty common to all art-making. Try separating the content of, for example, Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa from the painting itself and, surprise surprise, you tend to run into the same problem. (It can’t be a problem relating to the difference between a flat, chemical surface and impasto, can it?) A couple of sentences down there’s this: Part of the problem is that a photograph usually presents only one view of the subject, a singular truth. What follows this doesn’t satisfactorily qualify the statement toward much sense, unless you hold the idea of “a singular truth” as self-evident. The paragraph ends with: Appearances, as they say, can be deceiving. Indeed.

The book’s foreword is contributed by Ron Brownson, a senior curator at the Auckland Art Gallery for the past two decades whose ” … special interest is New Zealand and Pacific photography and video.” (3) Over that time he has curated two major photographic shows for the Gallery, each featuring the work of the individuals John Kinder and Marti Friedlander. The Gallery has long laid claim, with compelling evidence, to being the country’s premier art institution. And yet, with statistical evidence just as compelling, its commitment to producing New Zealand photography exhibitions has been minimal. It was quick off the block in the ‘70s with the seminal Three New Zealand Photographers show of 1973 featuring the work of Gary Baigent, Richard Collins and John Fields (and it may be of some significance that the honorary curators at the time were John Turner and Tom Hutchins), then in 1979 another Three New Zealand Photographers, this time with Laurence Aberhart, Fiona Clark and Peter Peryer. Rodney Wilson’s The Chelsea Project in 1984 celebrated the centenary of the sugar company and came closest to some sort of contemporary assessment. There was a hint of what might be possible with the photographic component of The 1950s Show over the summer of 1992/93, but the hors d’oeuvres on offer turned out to precede a non-existent main meal. So, apart from the two solo surveys already mentioned and the occasional appearance of a wad of images in general group shows, that’s about the grand sum total over forty years.

This is a woeful record, especially when - statistically demonstrable again - a relatively tiny operation such as Whanganui’s McNamara Gallery (in a provincial location but with a metropolitan programme) which has done far more foregrounding New Zealand photography over the past decade than the Auckland Art Gallery, with intelligent and enterprising group exhibitions such as fiction of 2004/05, A serious kind of beauty of 2009/10, and this year’s Available Light. Indeed, over the past four decades the AAG has never produced a single show about photography coming anywhere near the curatorial acuity, the intellectual weight and visual stimulation of these modest exhibitions - modest in scale but anything but in terms of achieved ambition. When the reconstructed building opened with great fanfare in 2011, an historical show of New Zealand art from the collection in the Wellesley wing claimed to be a comprehensive survey from colonial days to the present (4), but the earliest photographic image included was dated 1955: a whole century missing. Eventually, when the fog lifts, it may well become clear that what was missing was indeed central to such a survey.

PhotoForum has mounted regularly a number of notable photography shows in Auckland over the years, the aforementioned Open the Shutter: Auckland Photography Now of 1994 being just one of them. Another was Currency: contemporary photographic art the following year, guest-curated by Peter Turner, former editor of the UK’s influential Creative Camera magazine. As so many PhotoForum shows are, they were held at the Auckland Museum. Writing about Currency in Art New Zealand (5) Luit Bieringa observed rather delicately: “One might have thought that, considering Peter Turner’s pedigree as curator and editor of many years standing that he would have been presented with a larger stage upon which to display his expertise in the photographic area. The back-room, albeit it finely refurbished, exhibition space in the Auckland Museum is hardly the high-profile venue deserving of a belated review of photographic image-making in New Zealand today.”

In his PTWTM foreword, Brownson observes rather cheekily: “[This project] may well give one the impression of being an exhibition you could encounter at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, [the Gus Fisher or Te Tuhi] … Yet it is presented under the welcoming umbrella of Northart in Northcote, one of the North Shore’s most visited community galleries …” Northcote is even more distant from Kitchener Street than the Auckland Museum. Can we look forward to The Walters Prize relocating to Te Kuiti anytime soon one wonders? The local council’s marketers are bound to find a welcoming umbrella somewhere. But, Brownson continues: “I know of no pressing evidence that any public arts institution in Auckland has undertaken either a similar or even parallel project. Could this ambitious self-motivation result from the disquieting fact that photographic practice is not immediately associated with the tuition of New Zealand’s art history in Auckland? Or from the fact that the history of New Zealand photography and the history of Aotearoa New Zealand are so intertwined that art/photographic historians appear to repeatedly ignore their inter-relationship?” Well, as Eldridge Cleaver once said somewhat more succinctly “If you’re not part of the solution you’re part of the problem.”

Given PhotoForum’s early stated aims and the experience of Auckland members over the past four decades, one can only marvel at the meekness with which they’ve submitted to their marginalisation vis a vis the public gallery system there - to say nothing of the indignity of being praised for ambitious self-motivation when that very virtue is so conspicuously lacking in other quarters - a washing of hands on a scale to spike the envy of Pontius Pilate. Even allowing for the inward gaze of the ghetto, it’s still an astounding scenario. Oddly, though, both PhotoForum and the AAG are bound together by a similar modus operandi: neither of them seems particularly interested in the needs of those increasing numbers of non-photographers becoming more engaged with the medium. As a public for photography has grown steadily since the early 1980s, hungry for information, guidance and stimulation, PhotoForum members have continued talking amongst themselves and the AAG has continued with an exhibition programme as if New Zealand photography wasn’t happening. PTWTM manifestly convicts them both on all counts.

It’s always at least interesting to see the work of young, emerging photographers, but in an uncritical climate where promotion over-rides discrimination it’s all too easy to overlook the brutal fact that a chrysalis doesn’t fly, any more than an acorn can shade. For centuries artists of various kinds have aped current styles; that’s the nature of the game. For every Mozart there are a hundred Salieris. For every Edward Weston there have been thousands of - well, let’s not go there. The perhaps distressing fact for every aspiring Stieglitz or Gursky is that the vast majority of them are doomed to produce what critic Peter Schjeldahl once described, with chilling incisiveness, as “period décor”. The “contemporary look” may seem to have a freshness and edge at the time, but much of it proves to be cover versions of little lasting interest except, sociologically, as stuffing for budding careers or as footnotes to a history of taste. They say you can’t tell a book by its cover; but when the book consists of covers, what do we make of it then?

There is no doubt that PTWTM has superb production values. But then, so did the Nuremberg rallies. We’re back to the old Scholastic distinction between appearance and substance - admittedly a hazy area these days, but if anyone’s talking about (or even just assuming) any kind of excellence, it’s still a distinction with currency. Getting a stamp on your hand for achievement might work in Year One, but post-Year Thirteen in a culture with any depth it seems reasonable to expect a little more than just taking part.

Some years ago when Brian Edwards was running National Radio’s Saturday morning programme he once interviewed John Clarke, aka Fred Dagg, and they both reminisced about how easy it was to get on television in the ‘70s. Clarke said “Yeah, you just had to clear your throat and you were in the semis”, and something of this situation prevails in contemporary photographic practice. In the absence of anything resembling a rigorous critical climate just about any competent snapper can gain some traction. This lack of discrimination runs right through the photographic community, so that even practitioners with a real track record get enmeshed in projects such as this. Perhaps it just seemed like a good idea at the time?

Despite photography’s higher profile its recognition and acceptance are still very much on terms dictated by a largely conservative art world, more sensitive to maintaining its own status and power than making generous room for a medium with a quite different ethos and agenda. This year’s Auckland Art Fair featured a keynote presentation by Sandra Phillips, a photography curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and a commissioned essay by Ron Brownson - appearing at the front of the fair’s booklet and entitled “My photography addiction”. All this may have indicated a welcome focus on the medium, but it turns out to be a beauty very skin deep. Of the Art Fair’s 197 participating artists only 22 were photographers - roughly one-eighth - and 12 of them were from just two galleries: Whanganui’s McNamara Gallery Photography and Auckland’s Two Rooms. That leaves just 10 photographers spread over the other 35 participating galleries. Serious interest or token gesture? Take your pick.

On the verge of marking 40 years of its existence PhotoForum as an organisation can’t afford to assume that by producing books such as this it’s still meeting its original aims. What was relevant endeavour in the mid-1970s - publishing the contemporary work of members and fellow travellers - may not be so relevant in the second decade of the 21st century. Current needs centre on the wider public, not the needs of PhotoForum members. The organisation’s proud history of achievement can continue only if the ghetto is forsaken.

Peter Ireland

(1) To be fair, in his introductory essay to Mirrors and Windows Szarkowski does write that “The two creative motives that have been contrasted here are not discrete. Ultimately each of the pictures in this book is part of a single, complex, plastic tradition”.

(2) Although the writer of this piece was asked to contribute an essay to this book, he was not involved in the selection of photographers, nor in any aspect of the book’s compilation.

(3) Front flap blurb in Marti Friedlander photography, catalogue of a survey exhibition curated by Ron Brownson, a Godwit Book in association with the Auckland Art Gallery, 2001.

(4) The Introductory label to the exhibition entitled Toi Aotearoa read thus: “Explore our art history through the New Zealand collections of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki. This exhibition will take you forward in time from historic art, to modern, to contemporary and works from today. Toi Aotearoa focuses on key artists, artworks, themes and movements. You will see the development of Maori and Pakeha art, our colonial heritage, Pacific and international influences. Over the next three years the works exhibited in these spaces and the stories they tell will continue to change. Auckland Art Gallery’s New Zealand collections are valued for their depth and variety. Toi Aotearoa illustrates why.”

(5) Luit Bieringa, ‘Let’s Do Something: The Currency of Contemporary New Zealand Photography’, Art New Zealand 77, Summer 1995/96, pp 46-49.

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.