Peter Ireland – 1 March, 2014

This is perhaps the most distinctive marker in her work: a singular focus on the self - not as a narcissistic exercise starring her self, but making her own experience an emotional compass to find some direction in the flood of life's raw data, her photographs the distillations of this chaos, her imagery still anchor-points, secure guy-ropes supporting the fragile tent of knowable existence.

I

In 1920 Britain’s Lady Rhondda founded a magazine called Time and Tide, which - initially at least - had a pioneering feminist and left-wing orientation. After a chequered history it finally ceased publication in 1986. The notion of time and tide’s an interesting one: at various levels it applies especially to photography’s own timing as well as the tides of its own chequered life since being invented. But it also applies to any artist’s standing within the culture - not just photographers - with any practitioner’s current status being the result of a complex dynamic of perceptions, judgements and promotions that, perhaps surprisingly, can exist outside of what long-term value their actual work might have.

For instance, J S Bach in his lifetime was very much a provincial musician hardly known - Georg Philipp Telemann was the really famous German musical phenomenon of the time - and it wasn’t until Mendelssohn “discovered” him in the 19th century that Bach’s present high reputation developed.(1) In Mozart’s day his precocity was certainly the subject of European-wide comment, but the real insider of the time was Salieri, a man who knew how to manipulate princely courts and secure commissions.

Mid-way through the 20th century Picasso was the undisputed star of the art world, the kind of profile that not even a combined Hirst and Koons could wish for. His contemporary, Matisse, was, you know, all right, but a bit too “decorative” for high Modernist taste, and it’s only been over the last two to three decades that his work has been estimated as at least equal in achievement to the protean Pablo’s. Around mid-century, too, artists such as Morandi and L S Lowry were placed low in the hierarchy because of their perceived realism and, probably, the small scale of their productions. Now they have a higher profile than 1950s’ abstract artists such as, say, Robert Motherwell or Patrick Heron. Oh, time and tide! But then, Bob and Pat may yet roll back in on the next one….

Is it all “just” fashion? (Or, just “fashion”?) Fashion’s a loaded word and most often rolled out pejoratively, and more often than not indicating the user’s failure to get a grip on current change. Taking the word literally, though, look at the sphere of fashion photography: thirty years ago photographers such as Hoyningen-Huene, Horst, Beaton, Irving Penn and Richard Avedon were low in the hierarchy because their work’s commercial orientation offended against Modernism’s purist agenda, and the fashion industry’s apparent transience and feminine ethos was at odds with Modernism’s masculinist monumentality. Since around 1980, however, new histories of photography have been showing increasing interest in and respect for fashion photography, and indeed, for photographers born since then it’s no longer a problem - to the point that in many cases there’s little perceptible difference between current fashion photography and contemporary practice. There’s no anxiety about the mutual influence though, it’s just an easy traffic between the two. Modernism’s pejorative, verbal artillery of “fashionable”, “decorative” and even “kitsch” has been disarmed - diffused, even - by artists too young to take too seriously the old, uptight hierarchies. Which, it’s pertinent to observe here, also included the low place accorded photography in relation to other art mediums.

In the art world, of course - where there are no certainties - maintaining credibility depends on using reassuring words and phrases such as “important”, “significant” and “high-profile” rather than the more flaky-sounding “fashionable”, with the assumption fostered that within the curatorial profession such judgements are based on academic qualifications, art sector experience etc. More often than not those involved are keeping a weather-eye out for what the consensus is within their peer group - with any perceived deviation a likely threat to career prospects. There are no Thirty-nine Articles to be signed up to here; there doesn’t have to be. Coercion is less effective in forming opinion than implied social and professional isolation.

The recent adjustment in the hierarchies of art is small, however, and its impact smaller, than a more significant change since around 1980. Before then, public taste and the embryonic art market were lead by the judgements of curators and art historians, the (largely) disinterested nature of their scholarship allowing a reasonable synergy between the artist’s reputation and the longer-term value of the work. Since the 1980s, however, the situation has reversed; not only is public taste now driven by a muscled-up art market but it drives curatorial practice too, with the art historians following not far behind. A consequence is that any synergy between reputation and the likely endurance of the work has almost vanished into thick air.

Formerly, artists worked away - often for decades, sometimes in relative obscurity - developing their work, earning a reputation based on their achievement. Now, five minutes out of art school, they construct a profile and produce work with the aim of maintaining that profile, for as long as credibility can be stitched together and public interest held. A major element in that credibility and interest is sourced within the operations of the art market. If in the past the word “investment” got mentioned, the assumption was that decades would be involved. But the word was not much mentioned. Not because it was deemed tasteless to talk about money but because works were brought to support the artist and to identify with the country’s developing, independent culture. Call that “nationalist” if you like, but only you find the monetarist alternative more attractive, where works are resold barely after the paint has dried, and their function is more for social display than cultural commitment. The notion of “future” implied in the word “investment” is now in the ball-park figure of a fortnight. Given the ephemeral nature of most profiles it’s essential to resell soon as, otherwise you’ll find yourself left holding a very cold baby.

II

In an environment where profile = importance, what can be made of artists such as Bosworth who have been working steadily for almost half a century, have demonstrated achievement but who have little profile to speak of? No good looking to the curators and art historians now - you’ll just get a dressed-up version of what an auctioneer might tell you. That’s if the curators and art historians aren’t actually writing the blurbs for the auction catalogues, which has become a common practice. (If there was ever much of an ethical boundary in this scenario, it has disappeared into the thick air too.) So, why buy - or even show interest in - the likes of Bosworth? Too obscure for your friends, little social cachet (even a source of embarrassment to your peer-group) and with virtually no investment potential. If you confessed to simply liking the work your naivety would be observed with bemused tolerance, and if you hazarded that it might have some long-term value you’d be mentally despatched to Jurassic Park.

McNamara Gallery Photography’s website has posted an artist biography for Bosworth. It runs to 67 words (2). Her choice, it must be guessed, but such brevity is her style, and sign of a fierce independence that’s wholemeal bread to the buttering-up style of most contemporary profiles, those club-sandwiches of qualifications, awards, residencies and notable collections. She was born in Auckland in 1944 but not naturally disadvantaged by her present age at all - except perhaps in profile terms. She attended the Ilam art school in the early 1970s at a time when Christchurch had a lively, “alternative” art scene, mostly sited at the down-market suburb of North Beach, involving printmakers, photographers, film-makers and musicians as well as painters and sculptors, makers of books, committed feminists, soft-drug dealers, persons of mixed gender and a prevailing atmosphere of sexual and artistic experimentation. Other photographers on the scene were Jane Zusters, Paul Johns, Terry Austin and Josie Dudson. (3) It was an intense, inventive, stimulating incubation, yet to be officially acknowledged in the record or given any credit by the public gallery establishment. (Less likely now probably; those North Beach productions are hardly “sought after”.) Bosworth later post-graduated to Elam where she majored in photography, her staunch feminism, commitment to colour and “dumb” processes such as Polaroid not making her path there any easier. She wasn’t singled out. It was the experience of other women photographers such as Janet Bayly too.

The intensity of that North Beach scene has remained a marker in Bosworth’s work ever since. This focus is mirrored by the already-mentioned brevity that is her style. For instance, an artist statement for an exhibition titled Women’s Art at the former Robert McDougall Art Gallery in Christchurch in 1975 begins thus: “Through my camera I record my experience.” Further down she states: “Photography enables me to express very directly what I perceive and what I project”, the directness, perception and projection all key elements in her practice. The statement later includes this acknowledgement: “I feel a particular affinity for the work of Dorothea Lange and Emmet Gowin, both Americans. Both have an intimacy and directness that attracts me” - that directness again, and mention of an intimacy crucial to any understanding of her work.

The statement ends with this credo: “I cannot separate being a woman and being an artist”, reinforced by a statement made the following year in the book Fragments of a World: a collection of photographs by New Zealand women photographers (4): “I believe a woman’s capacity for relating to the world on an emotional and intuitive level is a great strength to bring to any medium.” Fragments was a book published to celebrate International Women’s Year and as such is symbolic of the time’s very conscious, politically-oriented project. How much of those ideals have survived in today’s corporate world is the subject of much debate around whether the world’s been positively feminised or women negatively masculinised by the will to power. The careerist strategies of many high-profile women photographers now might tend to suggest the latter.

Like fellow contemporary, the late Joanna Paul (5), Bosworth is mistress of the fragment, both artists keenly aware of the fragmentary nature of perception and recalled experience, and equally sceptical of the grand narrative’s claim to any kind of definitiveness. In her published Workbook Notes (6) in 2002 Bosworth makes reference to her “hands-on approach of cutting and tearing photos to make new forms/codes”, observing that “Some of my techniques relate to playing with paper dolls in childhood - cutting, organizing, controlling.” Another contemporary, Merylyn Tweedie, provided the text of a five-page spread of Bosworth’s photographs in the UK’s influential magazine Creative Camera in 1988 (7), noting that ” … she takes pleasure in rearranging time … and dislocating things … which become part of a writing of herself”, an observation and phrase of immense pertinence to Bosworth’s practice.

This is perhaps the most distinctive marker in her work: a singular focus on the self - not as a narcissistic exercise starring her self, but making her own experience an emotional compass to find some direction in the flood of life’s raw data, her photographs the distillations of this chaos, her imagery still anchor-points, secure guy-ropes supporting the fragile tent of knowable existence. In the 1970s her portraiture in general was more wide-ranging, but by the early ‘80s she concluded that “… photographing other people is problematic. There is the disadvantage of having to account for one’s work. In retreat from this, I began in the mid-1980s to move towards almost exclusively autobiographical subject matter, including self-portraits.” (8)

This interesting distinction between “autobiographical subject matter” and “self-portraits” points to the metaphorical and literal poles of the Bosworthian spectrum, and illustrated by perhaps the two best-known early images from this more concentrated focus: 1984’s Figure study/drowning (S) 1 (9) and 1985’s Self-portrait, where the photographer depicts herself prone on an iron bedstead. Of course, it’s a truism that an artist’s oeuvre, despite varying “subject matter”, is largely autobiographical, and in the case of an artist such as Bosworth who has written that “The journey is through the terra incognita of myself” (10) it couldn’t be anything else. In terms of the conventional self-portrait, there were seven out of the 44 images in her 2002 exhibition and three out of 50 in 2006’s. In 2014 there is none. Her “autobiographical subject matter” has rendered the conventional self-portrait redundant, the writing of herself editing out her physical appearance. The ongoing exploration of her unknown territory through that “autobiographical subject matter” finds form in another self; the written word. We talk of Cézannes, van Goghs, Edward Westons and Peter Peryers, and while these images may speak of the artists’ relationship with the world it’s their letters, daybooks and blog drawing a direct line to them.

“Inside us the dead” as Albert Wendt once so eloquently put it, and inside Rhondda Bosworth - genetically, metaphorically and spiritually - lies her late father Rowley, her images from the early 1990s referencing his life-long literary preoccupations. In the ‘80s her work often included historical snapshots of her mother - and perhaps other female relatives and family friends - but the increasing appearance in her imagery of writing relating to her father and his father is a new and significant phenomenon - playing a larger role in the framing of her self - and raising some more general questions about the nature of text as imagery. In this context much has been said about McCahon’s work, and while these discussions impinge on Bosworth’s image-making, the comparison between painter and photographer serves best to highlight a deep divide between the values of painting and photography.

III

Previous to this current exhibition, Booklet 1, Bosworth’s last solo show, Exhibit A, was eight years before in 2006 - also at McNamara Gallery Photography. As they say, a long time between drinks, and in terms of maintaining profile pure folly. But this photographer writes her own script and creates her own calendar. In the meantime there has been a period which, while seemingly productively fallow, has seen her reassess the work she’s done, becoming more protective of those aspects of it relating to the more permissive 1960s and ‘70s - child nudity, for instance - and others relating to the on-going complexities of some adult relationships. Bosworth’s self-confessed journey through the terra incognita of herself delivers a subsequent knowingness that can result in withdrawals as often as revelations. More time and tide.

The most obvious development, though, since 2006 has been her shift to digital and learning the tricks of new printing technologies. Combine her early moves away from black and white with her signature intensity and you get in this show a new colour often startlingly saturated. Her new work has the paradoxical quality of Peter Peryer’s: both a surprise and simultaneously a recognition of authentic authorship, where the unknown and the known join hands. Indeed, his practice is the only one her’s resembles in the slightest - even admitting an (irrelevant) disparity in relative production and Peryer’s sense of detachment as against Bosworth’s steam-rolling intensity.

Formally, Bosworth’s new use of the tondo here (in five of the twenty images) marks a new development, giving a complete-ist aura to her signature fragmenting - a kind of healing of the brokenness that in no way diminishes the separateness. There’s a telescopic quality, too, that only emphasises their intensity. There are other strategies emphasising such intensity: one; extreme clarity - evidenced in In the Garden - and two; a blurring that, paradoxically, has the same effect. In Bungalo [sic] garden this technical “lack of focus” is analogous to nature’s ungovernable force, the image almost the visual equivalent of Dylan Thomas’s poem “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower.” And in the image music the blurring of the three notes depicted suggests powerfully the very vibrations the medium so utterly depends on and that Pater said all art aspires to the condition of.

The main wall of the gallery hosts the eight images referencing the literary interests of the photographer’s father, images forming the heart of this show. These references, however, are not a case of any filial homage or paternal commemoration. There’s a parallel, for a start, between Bosworth’s writing of her self through photography and Rowley’s through literature - not only by what he himself wrote but by the poems he collected. Indeed, how many of us have not, unwillingly or not, written our selves through the words, literal or not, of our fathers?

The employment of texts in images immediately raises questions about the nature of the textual component: is it to be “read” literally, compositionally, or symbolically? In twos? Or as all three? McCahon’s five-decade - and compounding - use of text has been for many viewers the greatest stumbling block to comprehending his work. Francis Pound has observed: “The use of these texts is far from accidental. They are intended to mean, and to be read for their meaning. And their meanings are the product of specifically New Zealand circumstances. They are also, in a special sense, autobiographical” (11). There are three issues here impacting on a reading of any textual work: the literal, specific circumstances and the autobiographical.

Firstly, in Bosworth’s case, until recently, any complete literal reading has been stymied by the fragmentary nature of the texts and often their visual blurriness. Secondly, as to their relation to “specifically New Zealand circumstances” one can only guess as to what nationalist reference might make greater sense of them. (Given Pound’s own project, it would be somewhat ironic, perhaps, to seek such references.) If the phrase “New Zealand” were replaced by the word “human” speculation may prove more fruitful. And thirdly, by now, in relation to Bosworth’s work, the autobiographical aspect is pretty much a given.

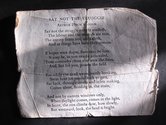

By comparison with with McCahon’s, Bosworth’s use of text is both more personal and more open-ended. The sonorously prophetic statements of a Biblical grand narrative are not her bailiwick. She’s more likely to photograph a fragment of the Dead Sea Scrolls than quote Ecclesiastes or Jeremiah. The nearest she’s come to any public declamation is depicting poems collected by her father, late 19th century works by now largely neglected versifiers such as Arthur Clough and W E Henley (12) Her texts are usually hand-written: self-generated, diary-like phrases so truncated they’re adrift from any specific meaning, or glimpses of correspondence where only the words at the centre are legible, such as in 2004’s Betty tells me. Compare such a phrase to, say, Lazarus come forth!, and you can start getting a handle on Bosworth’s intimacy, connection with commonplace human intercourse and avoidance of mythologising grandeur. (13) This is what photography does.

In the Pound essay already referred to, he quotes approvingly Wystan Curnow’s judgement on McCahon that “Death has been this artist’s overriding subject.” (14) With this artist death always comes with a portentous capital “D”, a looming presence casting its shadow over every joy and faith in possibility. As great as McCahon’s oeuvre can be, it’s a relief to recall Fomison’s throw-away remark that “Death is just Nature’s way of saying goodbye.” McCahon’s take on the subject is always grand and notional: when Bosworth depicts the poems her father collected, there is neither of these things. The probable scenario goes something like this: in a tolerable act of vandalism before going off to the Second World War, Rowley tore several of his favourite poems out of their books and folded them to fit in his wallet. Overseas, the elder Bosworth wasn’t speculating on the nature of Death; it was being faced in the lower case version on a daily basis, and these fragile literary talismans were part of his necessary protection. Their crumpled and frayed condition bespeak of much consultation and, probably, consolation. As images, these worn and humble objects, so starkly portrayed, convey touchingly the complex emotions of a man living on the edge. Their very muteness is their fullest expression.

Walker Evans talked about signature in relation to an artist’s style, drawing on the analogy between a person and their handwriting - which is how we come to describe certain works as Cézannes, Westons and Peryers - and this analogous relationship characterises these Rhondda Bosworth images when, superficially, they’re “just” depicting extracts from letters. It’s Tweedie’s “writing the self” again. Of course, such hand-written letters are rapidly becoming a rarity, and are thus as remote from our culture as monastic manuscripts became in Guttenberg’s time. What does this shift mean for personal expression of the self? Will writing one’s self become typing one’s self? Given the extended meanings of “typing” and the seductions of social media, this may already be true. Set the time, check the tide.

Peter Ireland

(1) At 80 years of age the composer and conductor Igor Stravinsky was able to write: “I was born out of time in the sense that by temperament and talent I would have been more suited for the life of a small Bach living in anonymity and composing regularly for an established service and for God. I did weather the world I have lived in - weathered it well you will say - and I have survived, though not uncorrupted, the corruption of spirit in the musical business world … and all of the misunderstandings about performance the word ‘concerts’ has come to mean. But the small Bach might have composed three times as much music.”

(2) The biography in the catalogue is even shorter; just 34 words.

(3) Josie Dudson was the subject of Jane Zusters’ still-potent Pink nude in a blue pool of 1979.

(4) Eds Gillian Chaplin, Simone van Delden, Hannah Donnelly, Sally Griffin, Angela Middleton & Frances Parkin; John McIndoe, Dunedin, 1976. All five Bosworth images included are portraits.

(5) See this writer’s piece on Robert Heald Gallery’s Joanna Paul photography show, EyeContact, 16 October 2013

(6) Introduction to Bosworth exhibition catalogue 44 Photographs: 1974-1999, McNamara Gallery Photography, Wanganui, 2002, p.4.

(7) Unacknowledged by Creative Camera, but originally published in PhotoForum no.56, 1987, pp 24-25.

(8) Introduction to Bosworth exhibition catalogue 44 Photographs: 1974-1999, McNamara Gallery Photography, Wanganui, 2002, p.4

(9) In a note written for National Art Gallery files in 1986, the photographer states: “A very significant image for me. I ‘dreamt’ the image and set about making it actual. I do not use other women as ‘models’, ‘posing’ (a phallocratic construct) - rather I arrest images from my sister participant’s own body language, set in motion by me in a 2-person ‘psychodrama’”. The “(S)” of the title refers to Sally Smith, the photographer’s collaborator in this case.

Probably unintentionally, these Figure study/drowning images connect with the earliest-known photographic self-portrait, 1840’s Self portrait as a drowned man by Hippolyte Bayard. Very self-consciously posed, this was the artist’s response to his significant contributions to the invention of photography being unacknowledged, his legitimate claims being elbowed aside by the more wily Daguerre’s. Probably, too, Bayard was unaware of laying the foundations for a phallocratic construct.

(10) ‘Some self-exegesis’, PhotoForum Review, no.31, January 1987, p.3.

(11) Francis Pound, ‘Endless Yet Never: death, prophecy and McCahon’s last painting’, essay in Colin McCahon: a question of faith, eds Marja Bloem and Martin Brown, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam & Craig Potton Publishing, Nelson, 2002, p.51.

(12) A 1996 image, Prayer Book, depicting two blurry pages from the burial service in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer is, perhaps, her most McCahonesque photograph.

(13) It’s a telling matter of scale too. McCahon’s Practical religion: the resurrection of Lazarus showing Mount Martha of 1969/70 measures 2075mm x 8070mm, whereas Bosworth’s Betty tells me measures a relatively tiny 180mm x 200mm.

(14) Pound, p.63

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.