Peter Ireland – 20 July, 2017

Under-scoring these often affectionate urban glimpses there’s a palpable melancholy: perhaps regret at not always improved change in the urban fabric, sadness at the amount of rubbish discarded, doubt about the brashness and superficiality of contemporary urban life. There may be plenty of bright light in these images, but there’s an elegiac quality too.

The taking of photographs is often a mix of spontaneity and opportunism - with an essential precondition of alertness - a matrix of factors centred on a concept of an immediacy which is seldom such a salient feature of other forms of art-making, which tend to seem both more conceptually considered and manually constructed. For photographers, the art involved often occurs before the image is made, and consists of their accumulated experience harnessed in a state of constant readiness: the very alertness already mentioned. The risk inherent in this approach is the images can look so casual, the photographers’ practice suspiciously random. We’ve heard the hoary ‘argument’ before: “Even my grandkids could do this.”

Nowhere is this scenario more evident than in so-called ‘street photography’, which is why the art market has been so slow to warm to it. The subject matter is just “too ordinary” (art is “special”, remember) and the formal qualities seem just too indiscriminate (and art-making is supposed to be a process of discrimination). In the hands of a master such as Peter Black, though, the images provide their own sturdy case for the defence. There’s nothing random or indiscriminate in his approach, and his eye for colour rivals the instincts of an artist as singular as Don Driver. It’s an appropriate irony his name should be Black.

James Gilberd’s street is a little quieter than Black’s, and his eye is drawn more to isolated objects and formal structures than the sometimes hectic and often teasing juxtapositions characterising the older photographer’s work. What they have in common is an ability to unmask the formal complexities and visual joys of the world within our view but which, until their images wake us, remains unapprehended as we go about our daily lives, seemingly in a daze and prone to easy distraction. Such photographs can be a gift to our own alertness too.

Gilberd exhibits rarely and plays a low-key role in the operation of Photospace Gallery - the longest-running photographic space in this county - his taste is catholic and spirit inclusive. There are few material benefits from his commitment to showing photography but his dedication to the medium has, over eighteen years, delivered a continuous succession of exhibitions showing a wide range of new work unparalleled by any other public space.

The appearance of A Coffee Break is the result of a cancelled show, but its unexpected origins are belied by the coherence and quality of the content, and the event is a refreshing and stimulating break indeed. It opens with a typically anonymous and sly ‘self-portrait’, Gilbert inserting himself into Window, Victoria St, 2015, the image an austere and abstract pattern of shadows, patterning repeated more fulsomely in I know what you did, lower Cuba St, 2016 - which doubles as an expert tribute to Lee Friedlander - and again in 3-7 Majoribanks St, Oct 2016, depicting the deconstruction of a commercial building, combining a marvellous exercise in abstraction with a touching human story: lower right a sign in a window announces “End of an era: we are moving to a new shop 28 Sydney Street, Petone - SOON!”

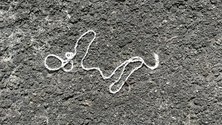

Gilberd’s skill in marshalling random details into coherent patterning is illustrated by Lorne St, December 2016 and Statuary, Makara, 2014. The former is saturated by hot colour suggested of an urban pulse, while in the latter the bright red of the ‘salvia bonfire’ is mitigated by the off-whites of the angel and dove and the brown/grey of the aggregate wall behind. And his ability to isolate objects and skew scale is evident in String, Mt Victoria, 2017 and Zip Fastener, Hawker St, 2016: the former turning discarded rubbish into a kind of urban signature, the latter’s skull-like appearance suggesting the grim outcome of continued environmental abuse. Gilberd-as-flaneur isn’t all beer and skittles.

Under-scoring these often affectionate urban glimpses there’s a palpable melancholy: perhaps regret at not always improved change in the urban fabric, sadness at the amount of rubbish discarded, doubt about the brashness and superficiality of contemporary urban life. There may be plenty of bright light in these images, but there’s an elegiac quality too.

The final photograph is literally an elegy. Johnsonville, March 2015 depicts a newly-constructed road for planned suburban expansion at the edge of Wellington, the road largely closed off by a series of concrete blocks. The three at the end have been turned into a memorial for a Jim McDonnell, the centre one bearing his name and a crucifix, the whole painted in the national colours of Ireland. This strange and affecting piece of folk art set in a dry landscape right on the border of the urban and rural carries the weight of a transience the medium of photography carries so uniquely and memorably.

Peter Ireland

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.