John Hurrell – 14 September, 2017

Whether the writers and their texts are incandescent in the way that Virginia Woolf (as referenced by Crowley) originally meant it I'm not sure. The resultant labours, it seems to me, can—nudged by the installation—be perceived in terms of a variety of qualities, such as emotional intensity, vividness and graphic acuity, an inner radiance emitting from the descriptive language or force of personality, or metaphorical transmission of feminist wisdom.

This presentation from Lisa Crowley comes in two parallel (but complementary) forms: a three channel video installation in Te Tuhi’s large Iris Fisher Gallery, and a take-away 24 page publication with five essays or (less expository) projects of creative writing that is available in the adjacent reading room. You might be absorbed by one and ignore the other, or you might conceptually integrate and enjoy the two, pondering in both cases the adjective (now a noun) ‘incandescent’ in its two meanings, that of glowing (from within) or illuminatory, or emotional or passionate: applying to images on one hand; and texts or authors on the other.

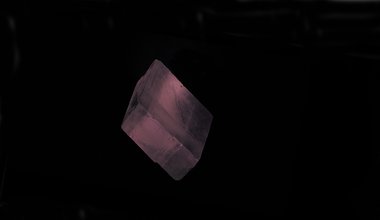

For the installation the long wall is used to maximum advantage with three alternating projections. In the darkened space a centrally positioned text tells us that ‘In order to calculate compatibility with an environment …she looks at the surfaces of planets…’ Backwards and forwards on the horizontal screen we see a sequence of ten isolated images, glowing chunky crystals of different hues, some flickering like a flame. (These can be compared to suns not planets.) The light passing through these translucent bodies makes them look like sucked sweets. The different spectral options allude to the hues we can detect of distant stars, winking coloured pin points in the firmament of the night-sky. Their colour depends on their mass which affects their temperature. Oddly the bluer ones are hotter than the smaller yellowy ones which live a lot longer.

Then come a series of about fifteen varied, highly textured and patterned aerial landscapes, based on online images of the planet Mars, accompanied by a rumbling bassy drone—the sound constructed by Clinton Watkins. Looking like close ups of gnarled bark, fissuring snow banks, rocky craters, leather, powdered sand or dried mud, these hovering pans of grey surreal landscapes are mesmerising. They come in groups and alternate with brief texts that give instructive research tips about analysing light to an unseen female narrator investigating distant uncolonisable environments, quotations taken from the seventeenth century astronomer Christiaan Huygens and his Treatise on Light.

The Incandescents publication was designed by Narrow Gauge and—as a ‘newspaper’—uses a tabloid A3 newsprint format. The texts from Gwynneth Porter, George Watson, Ngahuia Harrison, E. R Graham and Jan Bryant are positioned over double-page spreads (each sheet intact) of eerie, blue-grey Martian landscapes (slow pans of aerial shots of these contribute to the video), with the accompanying writing varied, interesting and intimate. Whether they are incandescent in the way that Virginia Woolf (as referenced by Crowley) originally meant it I’m not sure. The five talented contributors were approached because they—as writers—might provide insights into creative projects now produced in the current historical period of late capitalism. The resultant labours, it seems to me, can —nudged by the installation—be perceived in terms of a variety of qualities, such as emotional intensity, vividness and graphic acuity, an inner radiance emitting from the descriptive language or force of personality, or metaphorical transmission of feminist wisdom.

Jan Bryant’s ‘Weak men and disorderly women’ is an essentialist attack on patriarchal capitalism or as she puts it patriarchalcapitalism (ultra-understandable derision in the age of Trump), paired with a paean to ‘disorderly women’—in the spirit of titles of feminist magazines in the eighties like LIP or Antic.

‘Story about a Desk,’ from Evangeline Riddiford Graham, is an entertaining narrative about a co-habiting relationship between flatmates that gradually turns ugly—where guarded affability metamorphoses into fury—while Gwynneth Porter’s ‘Acid Mantle’ is a meandering account of her visiting her parents in Christchurch with her son, interspersed with a morning winter’s run and ruminations on Neil Young and extraordinary writers like Lydia Davis and Clarice Lispector.

A central trope in George Watson’s ‘Naming Identifying Passing Exceeding’ is that of incandescent light, in this case radiating from a candle made from sperm whale oil—extended then to rama (bark, grass and birdfat) torches, fire as metaphor (ahikāroa) for the sustaining of family loyalty, and the arrival of gas and electricity. She looks at the nuances of Māori visibility, a theme elaborated further in regard to photographs of whanau (and place) by Ngahuia Harrison in her contribution ‘This is where will remember you.’ [That title is correct: there is no omission.]

It is debatable whether the two parts of this show need each other, or are both essential for understanding the show. Though the discussions on paper are at times gripping, any overall connection (suggesting coherence with the installation) in my view is tenuous. However parts of the publication are memorably haunting—as written passages.

I’m attracted to the detail of the vivid descriptions (Porter: where thousands of tiny spiders and their threads spectrally affect the light of the early morning sun; Watson: the slicing of a whale’s tongue into ‘bible leaves’; Harrison: the details of a photograph that showed her grandfather when he was four; Bryant describing how she maliciously gave false information to a stranger on Ponsonby Road when he asked for street directions; Graham: her flatmate’s ‘resentful’ long exhalation of breath when the author entered the flat.)

Like the slow aerial pans of Mars, they mentally linger.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.