John Hurrell – 26 January, 2018

The Māori text on the wall, now illuminated through the darkness by the filmed Ngāti Tūwharetoa landscapes, becomes a clever structural device to tie the two sides of the screen together, giving the English words Washington sings—that we never hear, but which Burnett loves, written by Clyde Otis—a new meaning in translation; allied to Te Rohu's anguish.

Pakuranga

Shannon Te Ao

With the sun aglow, I have my pensive moods

Curated by Sorcha Carey and Bruce E. Phillips

18 November 2017 - 25 February 2018

Shown in (and commissioned by) the 2017 Edinburgh Art Festival and, but now reformatted for a single double-sided screen at Te Tuhi (who also commissioned it), Shannon Te Ao’s With the sun aglow, I have my pensive moods (2017) carries on exploring themes that first surfaced with video installations like Two shoots that stretch far out (2013-14) and A torch and a light (cover), 2015, drawing on his love of landscape, animals, waiata, emotional intensity, bodily actions, and the sensuality of black/white film.

From 2014 on Te Ao has seemed to be making more complex works, with several filmic components, several textual elements, and several viewer spaces. In fact, to come close to grasping With the sun aglow, I have my pensive moods, you need to watch and listen from at least two locations in the room—each time for the piece’s full duration—enjoying the darkness and silence around each side of the screen, as much as the flickering light, shifting aural textures and spoken poetry.

With Te Ao’s current project, two very beautiful black and white films—featuring parched (Rangipo) Desert Road landscape and dairy cattle from two parts of the central North Island-utilise one side of the screen. On the other side he shows a film of two women slowly dancing in a field of medicinal hemp (its oil is good for treating skin complaints) in South Canterbury—in colour. Their activity alludes to a similar scene in a film Te Ao is fascinated by, Charles Burnett’s 1977 movie, Killer of Sheep, set in the black community of Watts. In that dance the protagonist rejects his wife. In Te Ao’s film, the intimate image gradually darkens with the women still moving.

Interwoven in all this are two texts:

One is a 1846 lament written by Te Rohu (1820-1850) a Ngāti Tūwharetoa woman who suffered from leprosy she picked up from a lover who then deserted her. Amongst other topics, she asks for some proof of his allegiance. Te Ao (himself Ngāti Tūwharetoa) recites the text in English, but in other parts has the tune slowed down in a synthesised vocoder translation, also using the cattle-filled landscape as a contextual tribal backdrop to the pathos of the words.

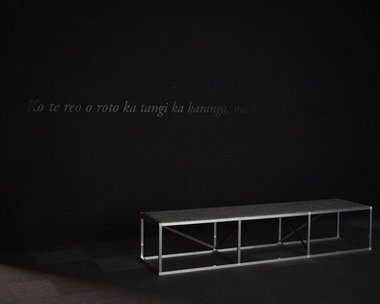

The other is a Māori translation of This Bitter Earth, a song featured in Killer of Sheep and sung by Dinah Washington. Some of its words Te Ao has put in a long line on the wall, using reflective vinyl. This text, now illuminated through the darkness by the filmed Ngāti Tūwharetoa landscapes, becomes a clever structural device to tie the two sides of the screen together, giving the English words Washington sings—that we never hear, but which Burnett loves, written by Clyde Otis—a new meaning in translation; allied to Te Rohu’s anguish:

But while a voice (ko te reo o roto) within me cries (ka tangi, ka karanga) I’m sure someone (mā tētahi pea) may answer my call (e whakaō).

It is a brilliant way of pulling all the ideas contained in this work together, so the elements gain a sense of inevitability with no loose ends; a successful anchor that tightens the concepts so that the piece is much more cohesive. Light, symbol and language come together.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.