John Hurrell – 12 December, 2018

Shepherd is not known for the wild looseness that is obvious in these paintings, but it (the ‘chaotic' scattering) works well and shifts his imagery towards a space far beyond illustration. The murkiness—so different from his usual pristine clarity—brings a great sense of foreboding disaster.

There are two suites of work in this latest Michael Shepherd painting exhibition: one four part project looks at the rapidly disappearing flora and fauna of our fields (some indigenous ‘weeds’ and a grasshopper); the other—that is subtly surreal in tone—with 6 units, looks at old standing steam engines. These are not the carriage-pulling railway variety, but big motors with stationary frameworks for doing outdoor agricultural, pumping or milling work, and smaller generators. Two different narratives alongside each other, with some commonalities.

The exhibition title, Suppose The Future Fails, comes from a Wallace Stevens poem, Owl’s Clover, but is not a direct reference or quote, more a tangential nod (…instead of failing …this future [never comes]), although lines from stanza 4 are written on the paintings. The title seems very apt today in planetary terms—with currently so little global optimism.

Over Shepherd‘s acrylic paintwork of sky and landscape is a polymer glaze in which are embedded many vegetative materials (varying from work to work) that include native and introduced grass seed, pasta letters, blessed thistle tea, muesli, plus some dead bees, iron sand and granulated carbon. Most of the images reference harvesting or threshing, showing particles such as dry chaff or stalks swirling through the air. Several have an ominously dark, apocalyptic ambience.

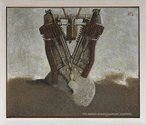

In many of the six engine paintings you can detect tube-like piston casings. In another, tubes that could be gun barrels, are aimed right at you.

With the piston forms Shepherd is referencing Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass and also the many (cross-sectioned) machine paintings Francis Picabia made around 1916-19. However Picabia and Duchamp were interested in machinery as an allegory for coitus and Shepherd’s work is not about that, but instead, much wider and grimmer in the scope of its nuanced surrealism.

I consider the most apt parallel to be Max Ernst’s disturbing painting, The Elephant Celebes (1921), which depicts a creature that is part elephant, part bull, part bathysphere, and part vacuum cleaner. In it you can detect the influence of Giorgio de Chirico who I think is also an influence on the Stevens poem Shepherd quotes.

Shepherd is not known for the wild looseness that is obvious in these paintings, but it (the ‘chaotic’ scattering) works well and shifts his imagery towards a space far beyond illustration. The murkiness—so different from his usual pristine clarity—brings a great sense of foreboding disaster. The turbulent air in these pictures is thick with what seems like dirt, specks of crushed straw and husks; blinding and smothering and getting in your mouth. Although mentally engaged, you almost choke and gag looking at them.

There is another painting, isolated from the above, that seems like it could be a satire on Alan Gibbs’ sculpture farm. It has a touch of a Mark Tansey allegory about it, with the small distant figures looking at something huge. In the foreground is an anteater searching for something a lot smaller. Perhaps ‘anteater’ really means ‘arteater.’ A fable about art consumption. A pointed narrative.

John Hurrell

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.