Peter Dornauf – 2 September, 2011

Hill draws a parallel between the nineteenth century furore over issues of the reinterpretation of God as a concept and a similar public debate engaging people today, but laments the fact that the conversation now seems polarized between atheists and conservative religionists rather than being focused on what he describes as the more complex, nuanced ideas of God currently being employed.

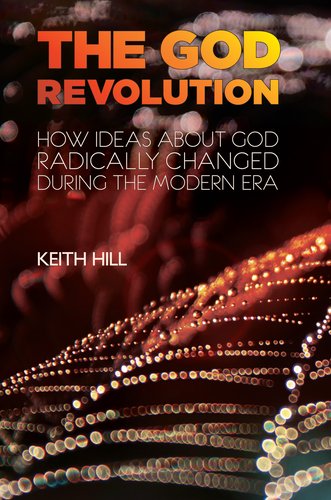

Keith Hill

The God Revolution

230 pp, RRP. $39.95

Renewed interest in the God question, prompted perhaps by 9/11, has spawned a plethora of books on the subject of religion, the charge led by a small group of writers dubbed The Four Horseman - Dawkins, Dennett, Harris and Hitchens. The little apocalypse they have provoked has seen a spate of further books published that add to the argument about the problematic nature of belief in the twenty-first century.

It is in this context that one of our own (not Professor Geering this time) has written a timely volume that takes an overview of how the concept of God has changed and morphed over the last few hundred years. Keith Hill has written a scholarly yet accessible volume that traces from Nietzsche to the present day how thinkers/theologians have been forced to reinterpret their concept of God to accommodate shifts in the mental landscape since the Enlightenment.

He draws a parallel between the nineteenth century furore over these issues, (Feuerbach, Renan etc), and a similar public debate engaging people today, but laments the fact that the conversation now seems polarized between atheists and conservative religionists rather than being focused on what he describes as the more complex, nuanced ideas of God currently being employed.

Succinct summaries of seminal thinkers like Tillich, Whitehead and others are canvassed, but while Hill traverses a good deal of ground in a clear and lucid manner, one or two prominent figures in the game do get left out along the way; people like Rudolf Bultmann and John A.T. Robinson.

The effects of modernism and its later critique by the postmodernists, is well covered and there’s an interesting chapter on whether religious experience points to a reality or is simply an internal psychological state.

The essence of The God Revolution is the story of the demise of supernaturalism and the history of theorizing about what is to be put in its place. It’s a fascinating narrative and Hill has done a commendable job in tracking its various twists and turns.

He ends by calling ‘God’ the word we use to describe that mystery out of which all reality has sprung, a God beyond mythology, metaphysics and religious dogma.

Books of this calibre, written and published here in New Zealand are a rare phenomena and this one deserves to be read by all those who care about ideas, the trajectory of civilization and its future form.

Peter Dornauf

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

Here is an article about atheism that examines a range of types of unbelief. http://newhumanist.org.uk/2657/varieties-of-irreligious-experience So I'm wondering can there ...

Ralph Paine

Like I said, everything’s more mixed up and in tension than that: aren't teaching and the writing of histories or ...

John Hurrell

Ralph, with your discussion of breaking the circle and stopping the regress etc you highlight the need at some point ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 11 comments.

Comment

John Hurrell, 12:24 a.m. 2 September, 2011 #

Some readers might be puzzled as to why a book about the history of God is being reviewed on an art debate website. Yet the histories of both manmade concepts are intertwined. And isn't art a secular religion anyway, or God the very first artwork? Opinions welcome.

Simon Bowerbank, 1:28 p.m. 2 September, 2011 #

The history of art is inextricably linked with pretty much anything you care to mention. I think its a slippery slope John...

John Hurrell, 2:46 p.m. 2 September, 2011 #

Well Simon, I was thinking of European art and the important role of Christianity there. That doesn't seem especially slippery to me.

Simon Bowerbank, 3:07 p.m. 2 September, 2011 #

I was referring more to the direction of this website.

John Hurrell, 5:28 p.m. 2 September, 2011 #

Huh,what? Look I'm hoping this site attracts stroppy types who love to argue. One of the topics I'm keen they look at is what is art itself - is there a definition, what kind of notion is it? Does it even make sense now to use the word 'art'? Especially as anything at all can be it.

The discussions about this entity called 'God ' are very similar in their intrinsic nature. And in this country - esp from the late forties to the early eighties - Colin McCahon's paintings raised issues about the viewer's belief in theological issues found in the New Testament, so Art World and Christian World clearly overlapped....ie I'm saying there is a logic to my putting such reviews on this site.

I guess I'm interested in atheism of both varieties.

Ralph Paine, 5:42 p.m. 3 September, 2011 #

It might be a case here of the difference between thinking and believing — think too much about definitions or founding principles and we risk aporias, circular reasoning, and vertiginous slides into infinite regress. At some point a decision has to be made, the circle broken, the regress stopped... And then the decision, break, or stoppage adhered to and kept as the instituting moment, the foundation. Once instituted the institution becomes a model for action, and we only return to its instituting moment at renewed risk. To adhere to and keep the instituting moment is to believe in it rather than question or think it. Belief is a “disposition to act” (Debray). Which of course runs its own risk.

John Hurrell, 3:16 p.m. 4 September, 2011 #

Well spoken Ralph. Artschools and seminaries are full of intellectuals whose propensity to 'over-think' has led to paralysis and long-term deferral of action.

Ralph Paine, 10:17 p.m. 4 September, 2011 #

Thanks John, but aren’t we more likely to find true believers in art schools and seminaries than anywhere else? Once established, isn’t it precisely these kinds of institution which provide models for action, with pedagogical models being perhaps some of the strongest? But I didn’t really intend any favouring of belief over thinking. Everything’s more mixed up and in tension than that, as there are always times when an over thinking of definitions and or founding principles suddenly leads to new kinds of action, as for example in the 60s and 70s with conceptual art, performance, etc.

John Hurrell, 11:30 p.m. 4 September, 2011 #

Ralph, with your discussion of breaking the circle and stopping the regress etc you highlight the need at some point to make a firm decision - to make art/believe in God, or abandon it. That crisis is common I think and many intellectuals get so wound up, self conscious or paralysed they jump ship. In art that means forgetting practice and becoming a teacher, historian or theoretician instead.

In saying that however I'm not decrying the value of thought.It's just that while perhaps belief can't be ultimately justified - if it needs to be - it is better to act (for unarticulated reasons) than not at all.

Ralph Paine, 12:53 p.m. 5 September, 2011 #

Like I said, everything’s more mixed up and in tension than that: aren't teaching and the writing of histories or theories modes of action? ... I do not adhere to the old dictum, "Those who can do, those who can't teach".

To be an atheist is to completely abandon God, to walk away. Likewise, to be a non-believer in Art is to walk away, abandon it (if, that is, one had been a believer in the first place). In this sense art teachers/historians/theorists have not abandoned art but are rather fully engaged actors/believers. And shouldn't we place critics in this category as well?

Of course none of this is to say that many artists/critics/historians/theorists/teachers/etc. do not at times embrace the risk of aporias, circular reasoning, and vertiginous slides into infinite regress, whether secretly or in a more open manner.

John Hurrell, 4:51 p.m. 20 October, 2011 #

Here is an article about atheism that examines a range of types of unbelief.

http://newhumanist.org.uk/2657/varieties-of-irreligious-experience

So I'm wondering can there be art atheists? Is George Dickie one with his institutional theory of art (or does he just not believe art has physical properties - they are social - but he is a believer none-the-less), or is Pierre Bourdieu another, with his theories of class distinction and art's role in that?

What do you thiink?

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.