Peter Ireland – 20 October, 2012

Portraiture is going feral too. It's where, more than ever in the past, you can be what you want to be. This projection of image - stylish, sophisticated, sexy et al - has at its heart desire. The desire itself is real enough, but as to the reality of the image, there's almost inevitably a disjunction of perception between the person projecting it and those on whom it's projected, and photography thrives in the gap.

Whanganui

Mark Rayner, Leigh Mitchell-Anyon & Catherine Russ

Dress Ups

14 September - 13 October 2012

The current debate - or is it just the usual ideological slanging match? - around same-sex marriage is a sign that the various waves of liberation movements, gender studies and three decades of deconstructing sexual roles and identity have finally reached the foreshore of parliament, where there’s also a pressing debate about the meaning of ‘ownership” and “rights” in relation to natural resources and the implications of the Treaty of Waitangi for government asset sales.

This is not a coincidence. Both sets of discussions indicate a re-evaluation of what the apparently fixed notions such as “man”, “woman”, “marriage”, “rights”, “property” and “ownership” might mean in a liberal, democratic, multi-cultural society in the South Pacific at the beginning of the twenty-first century. It is, after all, only a few generations since women were, legally, chattels in a marriage with few rights at all. Across the Tasman, aboriginals were granted the right to vote as recently as 1968, and the British parliament has yet to permit the eldest child of the monarch to automatically succeed if she happens to be female, or wants to marry a Roman Catholic. Then there’s the whole Republican debate, raising issues about the meaning of “nationhood” here and now. And let’s not get started on the very vexed issue of euthanasia.

There’s a phrase “art and life” which suggests a distinction between the two, as if art were an irrelevant past-time beyond the reach of oxygen, action and what Mitt Romney and John Banks are likely to call “the real world”. Yet here in Aotearoa, over the past couple of decades, in the areas of gender deconstruction and tino rangatiratanga it’s been the arts in the vanguard of sensing the shifts, defining the issues, foregrounding difference and widening the debate, and photography’s role in these processes has been pivotal.

Nothing fixed there either. The medium’s role has altered according to the shifting relationship between society and the subject matter. Just compare, say, Fiona Clark’s practice in the ‘70s and ‘80s to Yvonne Todd’s in the ‘90s and 2000s relating to notions of identity and you’ll get the idea. Even within a single practice such as Natalie Robertson’s, the line between her street signs in the ‘90s to her recent work on the East Coast has become a journey towards the meaning of Maori self-determination - for her as much as for the rest of us.

Clark’s focused aim and singular achievement within an honourable documentary tradition was to give visibility to the socially marginalised. Margins assume a centre, and that centre had a pretty fixed notion of what was what in the racial and gender departments. Straight as, bro. Her subjects weren’t claiming any special treatment, just a recognition they were there. Simple recognition at the centre, though, is enough to start blurring boundaries between core and periphery, a precondition for opening minds and changing hearts. One of the documentary tradition’s great gifts has been to make the experience of “the other” accessible, lessening the sense of otherness - so that what we have in common becomes the focus, not what separates “us” from “them” - and here only the names of Diane Arbus and Ans Westra need to be invoked to make the point.

These documentary projects have nearly always depicted people, but to what extent can these depictions be read as portraits? The projects themselves may be portraits of social issues and conditions, but the people depicted are more likely to be types than individuals. The portrait has a long, rich and very complex history, and the seemingly key issue of likeness is actually a very recent development -aided and abetted over the past 170 years, of course, by the medium of photography. For much longer - thousands of years - the portrait’s principal job has been to define status and cement the structures of power. Any attempt to read likeness into depictions of, say, the pharaohs or religious leaders such as Jesus is doomed by a confusion of political significance with physical appearance. The creation of image isn’t a recent product of Madison Avenue.

And the projection of image has remained at the heart of portraiture, even though a “successful” portrait has come to be judged on the approximation of likeness. “Yes, they’ve got the nose right” and so on. Despite the achievements of Arbus, Westra et al, the reverse has happened in a lot of documentary photography where image is imposed on the individuals being depicted, thus reducing them to the types often so eagerly sought by photographers, some more focused on projecting an image of “concerned photographer” than examining the nature of their own imposition. Those drunks weren’t alcoholics after all - they were just fed up with being photographed and took the (in)appropriate measures.

The idealisation processes of art before photography’s advent account for the visual and social formality embedded in portraiture: the subjects wear their best, look their best, placed in the most flattering position before an enhancing background, all too aware of being depicted. It’s been an enduring formula of image projection. Photography, naturally, picked up the formula and continues to run with it. Just look at those family groups featuring in the shop windows of professional photographers.

Thirty years ago the New Agey mantra of “you can be what you want to be” had traction, and the generation schooled in this, well, “philosophy” received (in the way that modern CEOs get performance bonuses) affirming stamps, stickers and certificates irrespective of their actual performance, leading to a firm sense of entitlement that quite often has rather tenuous links to what used to be called reality. It’s like smash and grab in slow motion. This generation has now graduated and, aided by Facebook and other social networks, is let loose in the world, powered by a belief that appearance, confidence, contacts, strategising and going forward will pretty much guarantee fame and fortune. The suspicion that actual intelligence may not be a strong element in this equation could, in a weak moment, partly explain current security cock-ups at MSD and teachers being victims of a less than reliable 300 million dollar pay delivery system.

Portraiture is going feral too. It’s where, more than ever in the past, you can be what you want to be. This projection of image - stylish, sophisticated, sexy et al - has at its heart desire. The desire itself is real enough, but as to the reality of the image, there’s almost inevitably a disjunction of perception between the person projecting it and those on whom it’s projected, and photography thrives in the gap.

The recent Dress Ups show at Whanganui’s Rayner Brothers Gallery brought many of these issues into sharper focus as well as providing a visually stimulating, rewarding and often amusing exhibition, which spans a more conventional documentary approach in Russ’s work, “new” documentary in Mitchell-Anyon’s and what might be called “post” documentary in Rayner’s.

At the end of the 1990s Catherine Russ looked at a revival of interest in ballroom dancing by a younger generation, thereby tapping into the origins of a broader enthusiasm resulting, for instance, in phenomena such as of Dancing with the Stars. Russ’s strategy was to photograph close up the faces of participants at the end of the evening, their sweaty and exhausted visages at odds with the image of glamour, extravagance and grace “ballroom dancing” tends to convey. One metre-square print entitled Matthew depicts a young man possibly about only 16, arrayed in a styley shirt and sporting a fashionable haircut but whose skin is, shall we say, conflicted by acne issues. This boy/man stares down the photographer, the mix of insolence and anxiety illustrating perfectly the contested border between desired image and brutal fact.

Leigh Mitchell-Anyon’s four but intimately related images potently depict four seemingly innocent purchases from a local Save Mart. Second-hand Barbie and Ken dolls in various states of dress/undress had been sorted and sealed in cellophane bags, the tops tied by a price label. What fascinated the photographer was the decision by the sorters to place three of the females in two of the bags and two of the males in each of the others. These models of an ideal, impossible anatomy, and paragons of sexual difference, have become, through their separation and in these photographs, something quite other. It’s as if these models, dead to current fashion, have been returned home in transparent body-bags allowing them to strut their stuff one more time. Opting for an ideal look in molded, enduring plastic, these creatures are doomed never to replicate - doubly doomed, given their Save Mart wrapping - and will take longer to decompose than the rest of us. And the same-sex packaging takes these half-dressed chums to a place somewhat beyond the marketing targets of Mattel Inc. (In this Dress Ups context, the Barbie and Ken story has an added twist. They started “going out” in 1961, but Mattel announced a split in 2004. Two years later they got back together again after Ken had a makeover.)

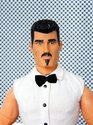

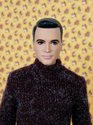

The makeover is the subject of Mark Rayner’s fake portraits. His Man Doll series depicts Ken-like figures in “bad taste” clothing in front of retro wallpaper backgrounds, but despite this set up they possess a curious individualistic credibility and sincerity - the sincerity of self-belief. There are sometimes revealing, laugh-out-loud chinks in this armour. One of the figures, an Aryan blond gym bunny with blue eyes, wears an outlandishly out-of-scale and homely cardy, “degrading” his projected image into something more humanly approachable.

The deathless pose of these plastic figures not only cautions about the sterility of the ideal but parodies with a degree of playful affection attempts to reach that ideal, an apparently limitless world of physical exercise, cosmetics and medical interventions, all set to provide clothes-horses for the latest fashions. Even the term “cosmetic surgery” has had a makeover: it’s now known as “appearance medicine”. Medicine? Oh, what ails us…. Beware though: the new photographic technology could be - is already becoming? - the appearance medicine of imagery.

Rayner’s post-camp, post-documentary, post-everything outs the pose of conventional portraiture and pokes fun at its pretensions and increasingly hollow claims on attention. His portraits are no less effective for their complete lack of any savage Goyaesque disdain. Like any serious photographer he accepts the world as it is, realising the futility of trying to flay skin that’s now a hundred percent plastic.

Perfect.

Peter Ireland

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.