Peter Ireland – 24 December, 2014

The artier end of photography may have become fashionable in the past couple of decades, but there remain aspects of it still overlooked, even though they are close to the heart of the medium itself. What’s called “street photography” is in this category. You can replicate Dutch still lifes and make a killing, but depict the seemingly chaotic verve of a very ordinary city street and you’re doomed to critical isolation.

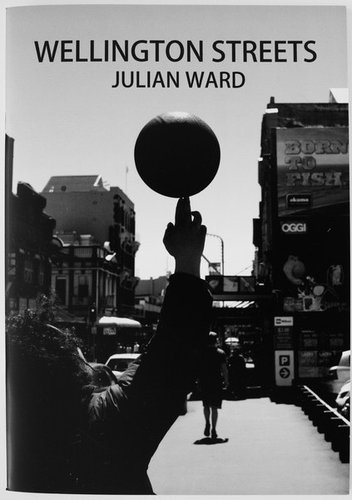

Photographs by Julian Ward

Wellington Streets

24 pages

47 images

Wellington, 2014

Richard Hamilton’s justly famous 1956 work Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? still has the power to surprise and delight, despite countless reproductions and its elevation to the status of “pop icon”, to say nothing of the artist’s own 1992 “remake” and 2004 “upgrade” - perhaps his way of preventing the image from being taken too seriously by the art history industry. Replace the word “homes” of the title with the word “art” and it’s a good question to keep asking, especially today when art production is so diverse and voluminous. But it’s a question asked and answered by artists rather than art historians.

The very recent publication of Julian Ward’s fourth book suggests there may be some merit in rejigging Hamilton’s title a little further: take out that “homes” and “art” and shove in “photography” and suddenly Ward’s images take on a new potency. They might be “about” life on the Capital’s streets, but they’re just as much about photography: just what is it that makes the medium so different, so appealing?

So much photographic imagery’s like a double-sided coin: on one side there’s the subject matter and on the other there’s, well, something else. Whatever it is it’s something to do with meaning, and that’s a whole bunch of stuff ranging from historical context to personal response. There is no fixed answer, only continuing questions. Of course, this lack of definitiveness can be seen in two ways: by sceptics who see it as a reason to reinforce their suspicion of art’s uselessness (and what a crew of wankers artists and art writers are), or by more seasoned viewers with a taste for enquiry - Mallarme’s “The world is rich, not clear” again - as an opportunity for reflection, challenge, intellectual enlargement and emotional satisfaction.

One of the inescapable elements in the bunch of stuff around meaning is, of course, fashion. In high Modernist days this was a pejorative term because it tended to undermine the prevailing fetish of originality - despite the pretty obvious fact (even at the time) that fashions in Modernism were as endemic as in any other art movement since competition first entered the equation between two Assyrian bass-reliefists. Complicating this business of art-world fashion is the seldom-admitted fact that most art consumers are like reef-fish, programmed to move with majority opinion, micro-sensitive to changes of taste and reputation. Taste follows reputation pretty much, and it’s a posse of dealers, art writers and institutions constructing reputations, with the auction houses following close behind, like James K Baxter’s dung-collecting householder - as critics behind writers - following a horse with a spade. At any one time there are always artists whose work falls under the radar because it’s perceived to be unfashionable (or, worse, a reputation has never been constructed around it) whose fate is to have their work appreciated only by later generations who have the perspective to differentiate between genuine cultural expression and period décor.

The artier end of photography may have become fashionable in the past couple of decades, but there remain aspects of it still overlooked, even though they are close to the heart of the medium itself. What’s called “street photography” is in this category. You can replicate Dutch still lifes and make a killing, but depict the seemingly chaotic verve of a very ordinary city street and you’re doomed to critical isolation. Even an absolute master such as Peter Black is relatively unknown outside of Wellington and relatively uncollected anywhere. If reef-fish suck (do they?), they could suck on this.

Julian Ward’s unlikely to star on a ten metre banner outside a metropolitan gallery anytime soon, but by now he’s built up a quietly significant body of work full of pulse and revelation. Like Black and their godmother Ans Westra he roams the streets with an unobtrusive skill and killer alertness, eyes tuned to the flow of life, not the machinations of the art market. But here the blinkers of fashion rule and Ward’s alertness is not at all matched by his viewers’ - even if they happened to stumble on his work. Not a name they know, you know.

The street tradition arose in Europe in the later 19th century, once camera technology had advanced far enough to capture rapid movement with clarity, but the style of the tradition was forged on American streets from the 1930s, reaching its apogee, perhaps, in the 1960s and ‘70s with masters such as Helen Levitt, William Klein, Gary Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, the earlier of these the precursors of England’s Tony Ray-Jones, for example, and other photographers worldwide, including John B Turner here (1) The vast majority of this imagery is black and white - another deterrent for current art-world interest - but as what passes for a photographic history unfolds, street photography in colour stretching back to the 1950s, such as Canadian Fred Herzog’s, is gradually appearing in published form and is, frankly, revelatory.

While securely in this tradition, Julian Ward’s work has its own spin, salted by his own sense of humour, which never, mercifully, descends into corniness. His patch is Wellington’s “Golden Mile”, a commercial highway beginning at the Parliament end of Lambton Quay and ending at the Embassy Theatre, or Hobbit, end of Courtenay Place. Ward, however, mines more of the precious ore in a smart detour up Cuba Street, perhaps New Zealand’s most interesting byway. While he clearly knows the geography of this path, what his camera tells us is that socially it’s fresh fuel for endless knowledge - and delight too, it must be said. “Delight” may seem a bit flippant for some of his subject matter, because while he brings an unjudgemental eye to his subjects, the intelligence behind it is not unaware of the ironies implicit in the social disparities his lens often portrays. He may not be an old-fashioned “concerned photographer”, but he’s not an unconcerned one either. The response to his admirably short “artist statement” on the title page - “Just outside my window is Wellington city where I wander most days with my camera” - just has to be “Yeah, right”.

As with Winogrand and Lee Friedlander his formal sense seems to be instinctive, a highly-attuned ability to frame an image in an instant. Seemingly snapshots, their structured excellence becomes all the more apparent the longer you look. What’s more, there’s a consistency in his oeuvre expertly replicated in this beautifully-paced book. It’s a very modest publication but it records much, much more than a modest talent.

Photography and the street are great mates. A strength for those who “get” the medium, a weakness for those many who don’t. But, it’s only 2014 and patience is, apparently, a virtue. Meanwhile Julian Ward and his like get on with the job of revealing how humans are in the spaces they inhabit. Not much still life there.

Peter Ireland

(1) Turner’s book on Te Atatu to be published by Rim Books next year will be worth the wait.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.