Peter Ireland – 21 April, 2015

In the 1970s, ‘80s and into the ‘90s the defining character of contemporary Māori art was protest. But as the issues being protested about came to some degree of resolution - however minimally - the tone shifted to something a little less confrontational, something more about difference and identity - celebration even - signalling a greater texture in the historical response and a more savvy use of both contemporary imagery and up-to-the-minute technology.

Whanganui

Isiaha Barlow, Tia Huia Ranginui, Aaron Te Rangiao and Sonny Barlow

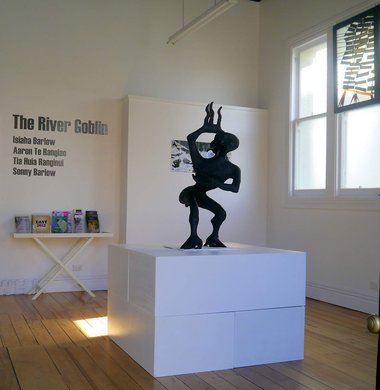

The River Goblin “Te Awa Tupua”: a Super Wairua production

6 March - 21 April 2015.

Think “commemoration” right now and you’re bound to come up with “World War I”. But, as Ngapuhi orator Richard Shepherd reminded those attending an Anzac Day service at Whanganui’s Moutoa Gardens last year, New Zealand’s connection with war started here, at home, in the 1860s. The alleged nation-construction represented by what happened at Gallipoli can be paired, uncomfortably, with a certain amount of nation-deconstruction caused by the confiscations in the wake of those Land Wars (1). What gets commemorated and when can tell us an awful lot about ourselves.

The wounds opened by the 79-day occupation of Whanganui’s Moutoa Gardens early in 1995 - or Pakaitore as Māori prefer to call the site - have not entirely healed. The seemingly eternal argument about the “h” in the town’s name is just one instance suggesting medical treatment in the form of historical recognition and reparation is still called for. That single, innocuous little letter is the symbolic focus of much festering misunderstanding, fear and resentment, and carries the burden of much yet to be resolved.

Every year in February since 1995 Māori have gathered at Pakaitore to commemorate the occupation and to keep the flame burning about the reasons for doing so. A disadvantaged people has every cause to nurture long memory: the Poles, the Welsh and the Irish are prime Western exemplars. Slightly over a century passed between the end of the Land Wars and the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal, and over that time every generation of Māori has persisted continually with petitions and protest until the justice of their case triumphed and found favour with the political process, if not with the electorate as a whole.

It’s not an uncommon perception that Māori are “ripping off the system”, but it appears to remain true that the combined monetary amount of Treaty settlements to date is yet to exceed the $1.6 billion Government bail-out of South Canterbury Finance in 2010 (2). What Māori lost unjustly for generations somewhat exceeded the losses suffered by those investors who placed their faith in Alan Hubbard. And for Māori the losses were not just monetary.

Art has played a conspicuous part in raising Pakeha consciousness about this cultural plight. Contemporary Māori art has long had a lively political agenda that Pakeha art is only now picking up on (3). The content of the most recent Walters’ Prize provides a handy example, and one rather pleasantly creating a certain unease amongst the Prize’s foundational patrons. Never trust art to deliver what you want. Artists may be hired, but mail order’s not (yet) part of the exchange when it comes to their art.

In terms of national profile The River Goblin‘s quartet of Whanganui artists are not “up there” with the likes of Brett Graham, Lisa Reihana, Shane Cotton, Peter Robinson et al, but as cultural warriors they’re all paddling the same waka. In the 1970s, ‘80s and into the ‘90s the defining character of contemporary Māori art was protest. But as the issues being protested about came to some degree of resolution - however minimally - the tone shifted to something a little less confrontational, something more about difference and identity - celebration even - signalling a greater texture in the historical response and a more savvy use of both contemporary imagery and up-to-the-minute technology. This is not an uncommon strategy among marginalised peoples. In 2003 a small group of urban Aboriginal artists in Brisbane, lead by Richard Bell, took the name proppaNOW, insisting that Aboriginal art was not to be corralled within a history of dot-making, and that any means of contemporary expression was equally open to them.

This is where The River Goblin artists sit. But they’re doing it in a specifically Māori way through their collective entity, Super Wairua. In Western cultural practice individual artists tend to lose their specific identity within a collective - like, say, the ‘80’s City Group - but in Māori culture individuals gain identity through a collective body, whether it be something temporary such as kapa haka participation or something more essential such as whanau, hapu or iwi (4). So, the addition of such tribal connections to a first and surname is not just a politically-correct affectation: it’s their full name, and they’re named so others know who they are.

Members of Super Wairua are aware the waka still needs to be manned, even if it’s sailing in calmer waters. Their natural waters are the Whanganui, made calmer by the recent settement whereby the government has recognised that a natural force such as a river cannot really be owned by anyone - no more than sudden lightning can be owned or the grinding motion of a glacier - so, in a uniquely New Zealand legal solution, the river’s acknowledged as an entity in its own right. (Remember, in Western law, it’s not much more than a century since such a recognition was applied to women.) Practically, this new legal status for the river allows for managing the resource, and since the settlement’s signing this will be shared equally between Māori and the Crown. This is something of an advance on what happened from 1891 when the first Wanganui River Trust was established by legislation to oversee “development” along the river - for the decades of its environmentally impactful existence the Trust had no Maori representation whatever.

The Whanganui’s individual entity has been named in the new legislation as Te Awa Tupua, and one of its translations is “the River Goblin”, giving the notion a supernatural dimension that simply naming fails to pin down: unlike individuals’ full names which tell us who they are, applying “River Goblin” to Te Awa Tupua is more an indication of possibilities than anything fixed. As well, the appellation is not merely a translation: it points to an entirely different concept - or head-space - and one at the heart of this exhibition.

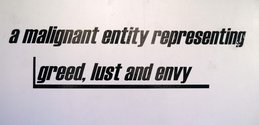

This complex concept is expressed in the form of a concern that Super Wairua poses by means of this show. And it’s one probably not readily comprehensible to most Pakeha. Perhaps a useful entry point to examining the concept is a wall-text in the show, a potent phrase “greed, lust and envy.” These are uniquely human traits, and not applicable to other life forms such as animals and, for Māori, rivers. The recent river Settlement is a human document, and so contaminated by human desires, and potentially complicated by human motivations, including political ones. In Super Wairua’s view the River Goblin is a malignant entity representing this greed, lust and envy which constitutes an offence to the wairua of the river.

The exhibition’s centre-piece is a sculptural representation of the River Goblin, a black, crouching, goblin-like form full of ugliness and menace. Its eyes and teeth are coated with gold, but in the process of being picked away, so Te Awa Tupua can return to the river and resume its guardianship purified of human traits. The sculpture’s combatative stance indicates it’s something of a battle to achieve the process of purification, and this war-like environment is further emphasised by a series of wall-based panels positioning the artists as warriors and, unapologetically, heroes.

The battle, though, is not just about this particular issue but refers to over a century of effort to maintain Māori values in the face of Pakeha “development” of the river. Four of the five panels are symbolic portraits of the participating artists, the fifth an acknowledgement of a further hero in this fight, the Gallery’s director, Bill Milbank - named Mahuruhuru for the occasion - who over the two decades of his directorship of the Sarjeant Gallery gave pioneering attention to emerging contemporary Māori art in both exhibition and collection terms. And just how contemporary is these artists’ deployment of the anime style to depict the imagery?

A further work is a short animated video also reinforcing the show’s central thesis. On the face of it it’s a crude piece of work, but no cruder than historical attempts to force Māori to conform to Western constructs, and, in any case, the video has the same earnest conviction of the Māori “folk art” of the late 19th century, using new forms to tell old stories.

The River Goblin is a small show about a big idea. Super Wairua may have used minimal resources to produce it but it packs a maximum punch. They see this exhibition as part of a series of interventions, so fasten your seat-belt and watch this space.

Peter Ireland

(1) It can be said, of course, that Māori never constituted a nation as generally understood in European terms, but rather a group of iwi collectively defined more by the shoreline of Aotearoa than by any sense of a shared nationhood. But whatever the nature of the description, there is no avoiding the widespread and real ill-effects of the land confiscations in the 19th century.

(2) A query as to the accuracy of this statistic was emailed to the Office of Treaty Settlements on 1st March but has not, so far, elicited any response.

(3) Earlier “protest art” by the likes of Hotere (over the proposed smelter site at Aramoana), Pat Hanly’s (over the visits of nuclear-powered vessels) and Allie Eagle’s (over the violence done to women) were exceptions proving the rule.

(4) What New Zealand’s first premier, Henry Sewell, once described as “the beastly communism of the Māori.”

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.