Peter Ireland – 21 December, 2016

By the second decade of the twentieth century, under the influence of the Modernist movement, the medium set out on a course more essentially photographic than aspirationally artistic. Although almost a century old this news has not quite reached a significant number of people, many of them the movers and shakers of the art world. The new(ish) language of photography still needs to be interpreted in a language already known to them.

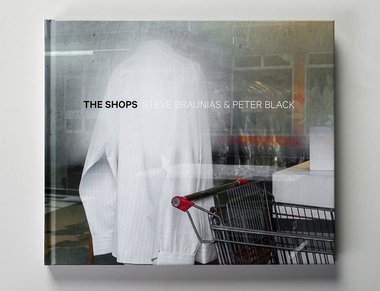

The Shops

5000 word essay by Steve Braunias

44 colour photographs by Peter Black

Hardcover; RRP: $40.00.

Many of the most basic things in life seem to involve some form of exchange. John Donne’s “No man is an island” gestures towards such an idea, that the give and take of relationships, their ebbs and flows, form the humming centre of human existence. The experience of relationships per qua begins, of course, with the personal one between the child, its mother and, increasingly, its father. Given the lack of comparisons - to say nothing of the child’s natural inability to sort their own experience - the young simply accept the exchange implicit in relationships as a given, just the way things are. Being cossetted in the bassinette of love is not conducive to self-reflection or critical inquiry (1).

Personal relationships are one thing, but commercial relationships are another. The earliest experience of these for a child could be standing on one side of a shop counter eyeing up the sweets available, then, with a guiding parent at their elbow, handing over the money in exchange for the preferred choice, thus being schooled not only in the protocols of shopping but learning something of the complexities that any relationship necessarily involves. Do I have enough money to acquire what I want? Will the shop-keeper growl me for being too slow to choose? Will he make any shaming remarks about what I look like? Will a bigger boy steal what I have on the way home? The pleasures of getting mediated by the anxieties of losing: doesn’t this equation lurk around the foundations of any relationship?

For many of the young, the glamour of shops and shopping is their first consistent introduction to the world beyond the domestic hearth. For those of Black’s and Braunias’s baby-boomer generation “going to town on Friday night” was often the highlight of their week. In the 1960s and ‘70s the advent of weekend shopping gradually strangled this joyous tradition, and now, online shopping threatens to put it out of its misery for good.

The Shops is both a testament to childhood nostalgia and a record of the slow decline of the high street as a social as well as a commercial centre. Braunias’s 18-page essay “Family shopping” settles on the former while Black’s 44 single-page images witness to the latter. It’s an interesting collaboration. Both writer and photographer had been aware and respectful of the other’s work for some time, and when Braunias approached Black suggesting a joint book he was ready for such an enterprise. There was an initial exchange of already-existing imagery to, as it were, set the scene, but after that each contribution more or less developed independently, ending in a pairing that dovetails perfectly.

Braunias’s essay is part memoir, the view of a pre-pubescent boy around 1970 growing up in a provincial New Zealand town. It’s also part meditation, a knowing exploration of the psychology of such a child, skilfully casting the recollection through the lens of childhood’s innocence. The writer powerfully and memorably recreates the intensely momentary quality of the child’s experience where immediacy has greater impact than any consideration of longer-term effects. Such as when his father, on leaving home for good, gives him five dollars, and as the car disappears down the driveway the author’s thoughts settle on what he might buy with the money and not on the looming implications of a solo parent family. For Braunias, shops and shopping formed an early matrix in his understanding of how the world works.

Peter Black’s images offer a matrix of how photography works. Forced to falsely claim itself as the bastard child of painting in the world of visual culture, the medium still struggles to establish its own legitimacy, despite the much higher profile it has found over the past thirty years. Born as the servant of scientific enquiry in the mid nineteenth century, photography soon hankered after artistic status, and by the end of the century an international style had developed known as Pictorialism which self-consciously aped the conventions of contemporary art. By the second decade of the twentieth century, however, under the influence of the Modernist movement, the medium set out on a course more essentially photographic than aspirationally artistic. Although almost a century old this news has not quite reached a significant number of people, many of them the movers and shakers of the art world. The new(ish) language of photography still needs to be interpreted in a language already known to them.

A key moment in the medium’s growing confidence in its unique contribution occurred thirty years ago with the exhibition in the US entitled New Topographies (2). In his catalogue introduction curator William Jenkins wrote of a “stylistic anonymity” and described the images as “stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion” and further noted a “rigorous purity, deadpan humour and a casual disregard for the importance” of the subject matter. Such values are at complete right-angles to conventional expectations as to what art should be about, hence the widespread reluctance to accept such imagery as legitimate - and valuable - cultural expression.

Peter Black’s work - exemplified by these images in The Shops - owes much to the New Topographies movement, as much a movement towards the unique values of photography as a movement away from the established values of art’s visual culture. Much of the latter can tend to the self-referential - art about art, especially since the advent of Postmoderrnism - whereas the former maintains a link with the urban and suburban world we actually live in. It’s an opposition between processes of idealisation and an acceptance of the poetry inherent in the rough particulars of the found world. The difference, perhaps, between sugar and salt.

The often austere and seemingly detached nature of work relating to New Topographies is never blank, simply a dumb recording of what’s registering inside a camera. The photographers are more often than not sharp social observers and even trenchant social critics, and there are few pages in The Shops where this photographer fails to register as both. There’s an affection, though, for the messily ad-hoc world he depicts and a benevolent tolerance of the failed dreams implicit in his photographs.

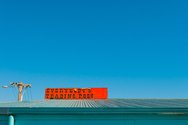

The tat of Black’s subject matter tends to conceal the high formal qualities of these images, and his sophisticated sense of abstract colour. Take plate 31 Temuka: mask the two small blue area at lower left with two fingers and the image dies. Do the same with the central pile of red plastic crates in plate 15 Martinborough and the same result applies. The signage, too, throughout the book - from the professionally generated to the hand made - collectively forms a concrete poem about selling, desire and faded hope. One example, plate 2 Paraparaumu, a peeling red sign set against a brilliant blue sky reads “Everybody’s Trading Post”, an epitaph for the common man.

Peter Ireland

(1) Many artists seem not to progress very far from this developmental stage.

(2) New Topographies: photographs of a man-altered landscape, curated by William Jenkins for the International Museum of Photography, George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, October 1975 - February 1976.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.