Peter Ireland – 2 January, 2018

Batchen's contribution, 'Surpassing in Fidelity,' is a Cook's tour around a single daguerreotype portrait of the Duke of Wellington (2), tracing its history as a reproduced image. Photography was fuel to the developing cult of celebrity (3) and as the ultimate vanquisher of Napoleon, Wellington was a national hero, with his later almost catastrophic role as prime minister seeming not to dent his popularity.

Wellington

Group exhibition

Apparitions: the photograph and its image

Curated by Geofrey Batchen and his Honours students

14 October - 17 December 2017

The convenient fiction of photography having a birth-date—19 August 1839—may gladden the hearts of those who (over)value simplicity, but such precision can disregard the messier details at the edges, the details which illuminate the bigger story much more interestingly than remembrance of any specific day, real or imagined. The Duke of Wellington’s strategy may have won the Battle of Waterloo on Sunday 18 June 1815, but who his most influential teacher may have been at Mr Whyte’s Academy in Dublin might well indicate the origins of that strategy.

Even a sketchy knowledge of how photography came to be—from the dreams of Giambattista della Porta in the 16th century to the experiments of Niepce, Bayard, Daguerre and Fox Talbot in the 19th—reveals that the medium took many twists and turns before it fulfilled the hopes of those who had imagined it. Photography’s entry into the world involved a very long labour and it took the classifying and cataloguing impulse of the 18th century to act as midwife to its eventual birth. It is hard enough now to imagine what an amazing thing the photographic image was when it first burst upon the world at the end of the 1830s, and even before the advent of now ubiquitous digital cameras and smartphones. Fixing an image congruent with perceived reality had been anticipated for centuries, and as is so often with scientific discoveries it was a sequence of hunches and accidents. Imagining the impact of ‘the silver miracle’ is now, almost literally, virtually impossible.

Until Sir John Herschel coined the term ‘photography’ in 1839 earlier attempts were known by various names, ‘heliograph’ (sun-print) being among them. Such images were either too indistinct or they faded quickly, but the first process to escape such technical transience was invented by the Frenchman Louis Daguerre—although he was canny enough as a commercial operator to play down the contributions of countrymen Nicephore Niepce and Hippolyte Bayard. (The latter was so distraught by the oversight that he portrayed himself in 1840 as a drowned man, thereby writing himself into art history as the first photographically staged suicide.) Many have followed, albeit unintentionally.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Apparitions is that it sites the advent of photography securely within the history of mechanical reproduction, and it investigates in detail the relatively short period where the two conspicuously over-lapped, leading to a mix of odd-ball ‘realisms’ which give the show much visual spice.

The daguerreotype, for all its marvellousness and uniqueness, is a hell of a thing to look at. The process resulted in a mirror-like surface which made the image either positive or negative depending on how one held the case in which the photograph was housed. Front on the image is largely invisible. And while Apparitions is rich in diverse examples, the point of their inclusion hinges on their utter uniqueness as objects, and thereby resistant to reproduction.

This exhibition is a group effort, a team lead by Professor Geoffrey Batchen and otherwise consisting of eight art history graduating students, each of whom pursues their own take on the topic and contributes a short but illuminating essay to the valuable, beautifully designed and amply illustrated 48-page publication. Moreover, the essays are consistently accessible, jargon-free and genuinely contribute to an understanding of this complex and lively period of photographic history (1).

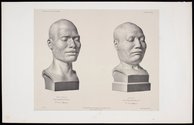

Batchen’s contribution, Surpassing in Fidelity, is a Cook’s tour around a single daguerreotype portrait of the Duke of Wellington (2), tracing its history as a reproduced image. Photography was fuel to the developing cult of celebrity (3) and as the ultimate vanquisher of Napoleon, Wellington was a national hero, with his later almost catastrophic role as prime minister seeming not to dent his popularity. Because of the medium’s early irreproducibility, existing media—such as mezzotint, etching, wood and steel engraving etc—had to be relied upon to spread his image far and wide. The exhibition includes this rich proliferation of Dukes—including, deliciously, a carte de visite which is an albumen photograph of an engraving after another engraving after the original daguerreotype. This just goes to show just how promiscuous the impulse was to spread photography-based imagery.

Peter Derksen’s essay, A Cult of Celebrity, addresses the relationship between photography and this social phenomenon more generally, while Frances Crombie’s Mirror Image, Social Device, examines in more detail just how the invention of photography triggered a seismic change in both the nature and democratic extent of portraiture itself. Also, not only are these early “portraits not just an image of an individual but also a reflection of a social identity. They affirm a class identity and its attendant values.” (4). This remains a significant aspect of formal photographic portraiture to this day. Informal portraiture in the form of the selfie equally affirms a sense of aspirational belonging—the medium translating the moment into history.

Nicola Caldwell’s Haunted and Haunting also examines this seismic shift in portraiture, but more conceptually, concentrating on the process of reproducing daguerreotypes, and the final passage of her essay could stand as an epigram for Apparitions: “The people in these daguerreotypes are ghost-like indeed, having been twice displaced from the bodies we see here, first by an act of representation and second by a repetition of that same act. They are the echo of an echo, having literally been re-remembered in photographic form. As with the lithographs and engravings in our exhibition, the originals are now lost to us. Just these copies of those other copies remain. Though mere apparitions, the people in these portraits nevertheless evoke a prersence that transcends the medium of their preservation. (5)”

Apparitions spans both the technical and social/cultural spectra of photography’s early years as it zig-zagged towards greater reliability of the images’ longevity, but with the negative’s early advent the medium blossomed in all directions, gathering pace from the 1970s so that today it’s not easy for anyone to keep track of global developments. In this rapidly expanding universe of images Apparitions marks the moment when that focus engendered by scientific enquiry concentrated the heat to make the medium of photography burst into life.

Peter Ireland

(1) It’s reassuring that at least one university in the Capital remains committed to readable—and stylish—language. The essays are: Peter Derksen’s A Cult of Celebrity; Kate Weaver’s Between Reality and Deception; Moya Lawson’s Real Spectres; Millie Singh’s The Lure of Authenticity; Frances Crombie’s Mirror Image, Social Device; Matthew Barrett’s Documents and Restless Shadows; Nicola Caldwell’s Haunted and Haunting; and Alys Pullein’s A Better Picture.

(2) Doubly unique, as this seems to be the only time the Duke sat for such a portrait, although as Batchen points out, the practice of the Adelaide Gallery studio was to take multiple images during single sittings. In 2017 a similarly unique Daguerreotype portrait of the painter Turner came to light, 166 years after his death. (Also reassuring is that the image bears not the slightest resemblance to Timothy Spall.)

(3) There were probably millions of carte de visites of Queen Victoria distributed, the first time most of her subjects knew what their monarch looked like.

(4) P.22.

(5) P.36.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.