Warren Feeney – 21 June, 2018

For a group exhibition that includes socially engaged artists like Phil Dadson and Jenna Packer the assumption that there will inevitably be a prevailing voice of protest in 'The Water Project' seems to have been reconsidered. Instead, the exhibition directs attention to other more subtle means of persuasion. There is a committed, yet objective, ‘step back' away from an authoritative voice, imparting words of advice and guidance.

Ashburton

Jacqui Colley, Phil Dadson, Bing Dawe, Bruce Foster, Brett Graham, Ross Hemera, Euan Macleod, Gregory O’Brien, Jenna Packer, Dani Terrizzi, Elizabeth Thomson, Peter Trevelyan and Kate Woods

The Water Project

Curated by Shirin Khosraviani

12 April - 22 June 2018

The Water Project is a group exhibition of work from thirteen artists that seeks to “challenge, inspire and call to action every individual inhabiting the natural world.” Such aspirations might initially sound like one of those media declarations made by the country’s larger public galleries, but The Water Project is different. It delivers on the sentiment of its claims and the credibility of what it calls on to respond.

It is a timely exhibition, but how did it manage to create such a conscious sense of responsibility towards addressing questions about the declining state of Aotearoa New Zealand’s rivers and lakes?

Part of the answer is that The Water Project has been extensively well planned. Curated by the manager of the Ashburton Art Gallery, Shirin Khosraviani, it began with a seminar in March 2017 at CoCA Gallery with the artists spending the day with ten speakers with expertise in issues around water and conservation. The list included: Te Marino Lenihan, Ngā Tahu and Co-Chair Ōtautahi and advocate for iwi values in the natural environment; landscape architect, Di Lucas; Eric Pawson, Professor of Geography at the University of Canterbury; and Rosalie Snoyink, a founding member of a number of influential conservation groups.

Khosraviani and the participating artists then undertook the necessary onsite research, traversing South Canterbury and the Mackenzie Country, meeting with locals, iwi, conservationists and others before making the work. There is an agreed-on respect from the artists for their chosen subjects, and this is also evident in the experience of the exhibition, contributing to its integrity and voice of reason.

It should also be noted, in relation to the context for the exhibition, that the township of Ashburton, where this touring show had its genesis, was established over 160 years ago as a service centre that was respectful of the authority of its farming community. Dairying supplanted sheep farming as its primary agricultural growth industry in the mid-1980s and, like the Waikato, effluence in its waterways has correspondingly increased.

Yet, for a group exhibition that includes socially engaged artists like Phil Dadson and Jenna Packer the assumption that there will inevitably be a prevailing voice of protest in The Water Project seems to have been reconsidered. Instead, the exhibition directs attention to other more subtle means of persuasion. There is a committed, yet objective, ‘step back’ away from an authoritative voice, imparting words of advice and guidance. Rather there is a preferred tendency to draw attention to the detail of the natural world. The participating artists may work in a diversity of media, but they collectively act a bit like botanical artists, often realising images that record or reference the organic, the sensory, or the micro and macro, enlightening us about the means and methodologies of nature.

Ross Hemera (Waitaha, Ngāti Māmoe and Ngāi Tahu) has positioned an installation with a waka, Ko Kārewa te Whakarare, in a central gallery space, giving weight to the wider context of the issues that The Water Project highlights. Ko Kārewa te Whakarare includes greywacke riverbed stones with figures inscribed from ancient rock drawings, determining a line from the past to the present and a relationship between the land and its people.

It is a sincere and reassuring adage that The Water Project both honours and scrutinises. Brett Graham’s (Ngāti Koroki Kahukura) video installation, Plus and Minus, is a checkerboard of minimalist circular modulating forms, black and white images that take their subject from the responsibilities and tasks of being a dairy farmer. The subjects in Graham’s videos are effluent spreaders, used by Waikato farmers to redistribute cow-waste onto paddocks to minimise chemical fertiliser use and divert waste from the Waikato.

There are many questions and initial deceptions like this throughout The Water Project. Peter Trevelyan’s Flow is one of his meticulous skeletal structures that in its appearance communicates ideas about certainty and reassurance, yet in the floating spaces in which it exists there is also an awareness of Flow’s precarious fragility. It shares this sentiment with Dani Terrizzi’s Concentrate and ask again, a floor projection of shifting colour, light, sound and form that conveys a tangible encounter with the realities of the natural world, yet without any need to pay attention to a particular location.

Bruce Foster’s matching set of five videos, Murmur 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, look like they sound in their titles, slow moving organic forms in the continuing process of regeneration and evaporation. I remember Foster’s documentary photography from the 1970s and one of the pleasures of seeing The Water Project is to rediscover his practice. There is a mutual spirit and iconography to Foster’s works in Elizabeth Thomson’s photographic reliefs, Sentients and Between Memory and Oblivion X1, although the scale of Sentients makes them more uneasy in their intention, as though the premise of ‘being’ is a conscious and difficult one, yet equally a necessary action.

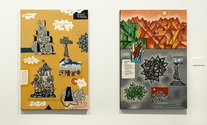

Jacqui Colley’s Method #1, Phenomenon #1 and Phenomenon #2, and Twitch are much closer in their subjects to a representation of place, being large-scale paintings and drawings that are cartographical in principle but mapping the intimate detail and spirit of the natural world. In Colley’s work, as it is in many of the other artists, observing the presence and realities of nature is qualified by a sense of both its enduring longevity and its possible demise. Jenna Packer’s painting Let that River carry your Folly away and wash you clean, is a panoramic triptych, alluding to the Tree of Life or Garden of Eden and, as its title suggests, seeking the assurance of renewal—but in a landscape uncertain of delivering such a promise.

Phil Dadson’s Braided Blues is a concrete poem, a large-scale work on paper of a perpetuating idea—HEARTHEARTHBREATHEARTHEARTHBREATH—and his video, Cow Cow Blues pointedly reveals the extent to which he is capable of adopting alternative perspective on his subject. He delivers a questioning and poignant response to the consumption of the earth’s resources and the absence of any accountability from global capitalism..

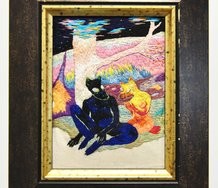

As would be expected, Euan Macleod’s Rain Man Over Ashburton takes place in a monumental landscape, yet, on this occasion, it is presided over—rather than occupied—by a lone figure. This is an interesting work from Macleod and one that confirms the extensive range of his iconography and practice.

Macleod also teams up with Greg O’Brien in a series of collaborative paintings, the best of which is Canticle of a mid-Canterbury Stream, where text and paint take up an agreeable conversation. O’Brien’s paintings also bring together pictures and words, and of these Ode to a water molecule and Five Canterbury rivers is notable, a work that eulogises familiar names from childhood; the Hakatere, Rangitata, Orari, Opihi and Waitaki rivers.

Bing Dawe is an artist whose practice is often closely associated with the country’s rivers and lakes. Downstream under Aoraki —Tuna with Barrier is dedicated to a Mid-Canterbury resident from Hinds, John Wilkie and his transporting of tuna and tunariki (baby tuna) both downstream and upstream over the dams on the Waitaki River. Dawe’s crafting of his subject and the symbolism of its positive and negative spaces as the presence and absence of life, makes Downstream easily among the best of his works.

Kate Woods’ appropriation of found watercolours of the landscape, with geometric objects floating in and off the surfaces of her collages—Waiau River (Richmond, Severini) and Waimakariri (Attwood, Oppenheim)—disrupt any ideas of gazing into these scenes to secure a sense of ownership. Instead, Woods’ images target the gallery visitor, directing their attention back into the space that they themselves occupy.

Woods’ collage works are also a reminder of a local history of European landscape painting that is comprehensively up for review here. If painting in Aotearoa New Zealand began in the mid-nineteenth century with the landscape as a subject for trophy hunting, and progressed to the parochial jingoism of Regionalism in the twentieth, then the measured humility and respect towards the land in The Water Project reiterates an important philosophical shift about our current relationship with the natural world.

Warren Feeney

Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.