John Hurrell – 27 September, 2019

De Lautour's paintings can be seen as loosely stacked chordal clusters, ideational cacophonies that mentally bombard the reader once the configurations have been deciphered to glyph forms; once the semi-cubist 3D pictographs have been translated into alphabetical tabulation. They then become musical scores or transcriptions of phonetic poems.

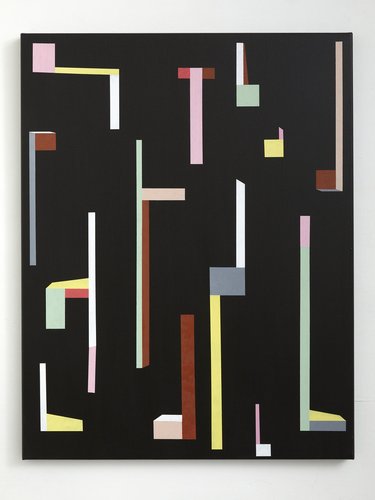

Tony de Lautour‘s three paintings feature morphological (architecturally related) riffs on letter shapes. These contain vertical bars (attached to blocks or slabs) which collectively create a kind of bouncy pulse throughout the dark void they hover in. However, they are also interesting for other reasons, to do with the mental sounds the individual jiggling letters—usually consonants—make (consciously, or possibly subliminally) in the reader’s mind.

Whilst you could compare them with textual poems constructed to be read aloud (like say, Michael McClure‘s Ghost Tantras with its animal noises), they are also related to the very abstract, less literary, very physical phonetic poems of Kurt Schwitters or Henri Chopin. These sound artists emphasise the aural experience, the sonic encounter that overshadows the visual—they create recited textures for the ear that are able to be performed.

So with this ‘logic’ in mind, de Lautour‘s paintings can be seen as loosely stacked chordal clusters, ideational cacophonies that mentally bombard the reader once the configurations have been deciphered to glyph forms; once the semi-cubist 3D pictographs have been translated into alphabetical tabulation. They then become musical scores or transcriptions of phonetic poems.

Also some of the letter shapes are backwards or upside down, so that introduces the technological achievements of Geoff Emerick and the Beatles—and earlier, John Cage—where recording tape is played reversed. That possibility requires considerable mental gymnastics on the painting viewer’s part, to imaginatively envisage very short bursts of enunciated sound treated in such a fashion.

De Lautour‘s letters fascinate as well through their three dimensionality, as if they were sculptural reliefs projecting out from the darkened walls of rooms or caves we cannot see. They have thicknesses, solidity and mass, and perhaps affect the proprioception of the gallery visitor walking past; their sense of bodily location.

These floating graphemes (called ‘contrastive units’ in Wikipedia) hover at different distances away from us, floating in deep space—some advancing, others receding; we can’t tell which. Their phonetic signifieds—like their spatial location and trajectory—are unstable too, constantly evolving through the contingent processes of history. Like the vagaries of interpretation and qualitative evaluation, the sound fragments they represent change over time. Music, literary and art histories, all slipping and sliding around buffeted by the day’s current political urgencies, and never ever becoming fixed or attaining certainty.

John Hurrell

Recent Comments

John Hurrell

For readers interested in the notion of media being impure (or not isolated)--as in say de Lautour's painting--this article by ...

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 1 comment.

Comment

John Hurrell, 9:37 a.m. 1 October, 2019 #

For readers interested in the notion of media being impure (or not isolated)--as in say de Lautour's painting--this article by Tom Mitchell ('There are no visual media') may be of interest.

http://www.mediaarthistory.org/refresh/Programmatic%20key%20texts/pdfs/mitchell.pdf

My pdf link seems to have dissolved. Here is an abstract.. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1470412905054673

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.