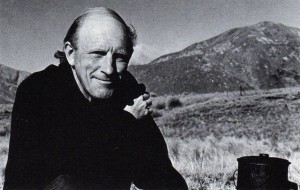

Peter Ireland – 20 February, 2014

Cleveland was also a pioneer in taking popular culture seriously, at a time when people of taste and discrimination routinely treated its rowdy embarrassments with condescension. Lawrence McDonald summed him up thus: “If you can imagine a man who is part Walker Evans, part Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, part Alan Lomax, and part Raymond Williams then you’re getting close to Cleveland’s turf.”

The annual horse-racing day at Kumara is a social institution on the West Coast. The tiny settlement, once a thriving gold-rush town with dozens of hotels, somehow still maintains, however notionally, a racing club superintending the yearly race-day. In 1959 I was there, a 12 year-old, trying to make some sense of this ritual posing as a sporting event. Up until then, my only experience of photographers was of a couple of slightly seedy men running impoverished studios out of dilapidated buildings in Hokitika who operated within the conventions of lining people up according to height and, in the studio, using artificial light and a range of props whose main function seemed to be various kinds of concealment.

At Kumara that day I noticed this guy with a camera skulking around, taking photographs of seemingly non-existent subject matter. It was very odd, something completely outside of my experience, and I was dutifully puzzled. It was Les Cleveland, documentary photographer. When his The Silent Land came out from the Caxton Press in 1966 I recognised a certain character in Plate 54. Some of my less-than-kind friends have remarked on my proximity to the entrance of the members’ bar, but in fact my presence was philanthrophic rather than alcoholic. A kid I knew at school had got the string attached to his sun-hat in a knot, right up under his chin, and I was helping to disentangle it.

In 2000 a mutual friend told Les this story - with characteristic generosity and thoughtfulness - he made a new print of the image and gave it to me. On that day in 1959 neither he nor I knew the full import of that crossing of paths. The photograph may have recorded a particular event in fine documentary tradition, but it came to commemorate - at least for me - a highly significant moment in my life.

(Just a few months later, in 1960 during Westland’s centenary, there were various celebrations throughout the province, including a kind of Big Day Out at Ross, another small settlement/former gold rush town south of Hokitika at the then end of the Midland railway line, originating “over the hill” in Christchurch. Another photographer was seen to be skulking about, randomly clicking away, so, clearly, the Kumara guy wasn’t a one-off. This was stuff people did. The Ross guy was Brian Brake.)

Cleveland’s recent death has sent me back to the catalogue of his survey show at the Wellington City Gallery in 1998, Message from the Exterior: Six Decades. Such recognition was a bit late in coming, but Les was of an old school where careerist expectations were non-existent, and it would’ve been all fine with him. Lawrence McDonald’s astute curation and invaluable catalogue essay, A Dwelling With Many Rooms, stand as a fair and fitting tribute to his photography. But, as Lawrence pointed out, Les was also a singer, a song-writer, a poet and short-story writer, a soldier, a journalist, broadcaster, folklorist, protester, bushman, occasional welder, social media sociologist and distinguished academic at VictoriaUniversity. He was also a pioneer in taking popular culture seriously, at a time when people of taste and discrimination routinely treated its rowdy embarrassments with condescension. McDonald summed him up thus: “If you can imagine a man who is part Walker Evans, part Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, part Alan Lomax, and part Raymond Williams then you’re getting close to Cleveland’s turf.”

Laurence Simmons’ essay in the same publication, Looking Back: Les Cleveland’s poetics of documentation, examines the apparent distinction between the “poles of aesthetic or documentary intent and effect”, having implications across the board, not just for Cleveland’s work, and offering an erudite and thoughtful meditation that still remains largely unconsidered in the art world.

Earlier, though, Cleveland’s work found its first major foregrounding - when Les was 64 - in Athol McCredie & Janet Bayly’s fine 1985 PhotoForum publication Witness to Change, still one of the best photographic books to have been published in New Zealand. Sub-titled Life in New Zealand, Photographs 1940 - 1965, it took three photographers in chronological order - John Pascoe, Cleveland and Ans Westra - to illustrate the strands of embryonic social documentary photography in this country. McCredie’s four and a half-page essay sensibly allowed Cleveland to pretty much speak for himself, because he was a considered thinker and memorable writer, with the dozen full-page illustrations so deftly seen through the press by Brian Moss that they allow the photographs to speak for themselves too.

Cleveland’s lifetime achievement as a photographer is enormously significant, and that will become more apparent as time passes. That the reception of his work in the present day remains stalled is something explained by Simmons in his 1998 essay: “Part of the problem with the collision between the terms documentary and poetics has to do with the widely accepted distinction between documentary and art photography and the subsequent assigning of documentary to a marginal zone”. The essayist goes on to link Cleveland’s work with Barthes’ notion of the principle of adventure in all photography, that unexpected journey between image and viewer, and concludes that this adventuring is the very condition of Cleveland’s work, providing its “power but also the repository of its grace.”

Cleveland’s own adventuring has ended, but his work’s has just begun. Vale dear Les.

Peter Ireland

Thank you PhotoForum for graciously allowing this reprint.

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.