Peter Ireland – 5 February, 2014

Barthes' classic definition of photography that it provides evidence of what had been is wedged between two significant assumptions. The first is on a conception of time that is linear and progressive, and secondly that making sense of “what had been” will be universally and eternally consistent. In the decades since Camera Lucida was published in 1980 both these assumptions have undergone some pretty rigorous examination.

Whanganui

Ben Cauchi, Dan Estabrook and Wayne Barrar

Seasoned: contemporary salt prints

6 December 2013 - 24 January 2014

Fixing the fleeting image, like the ability to fly, had been a dream of humankind’s long before photography’s clumsy efforts began bearing fruit in the 1820s. The artist’s camera obscura may have captured scenes but only delayed the fleetingness. The butterfly had been caught in a jar but was not yet pinned down in the museum drawer. For those photographic pioneers, having the experiences of seeing replicated in permanent form must have been a startling thrill that we can no longer relate to, saturated as we are on a daily basis now by a proliferation of images at such a speed as to bewilder proliferating bacteria. What had been a marvel has become a nuisance.

As with most technological advances, photography both came to be and was developed through a series of earnest experiments intersecting with miracles of good luck - the former relying on the predictable nature of chemicals and the latter the unpredictable nature of environmental circumstances and simply staggering coincidences. In the days when the first crude images were known as heliographs - sun pictures - the range of chemical experimentation was very hit-and-miss. And while at the level of realism these resulting, early, blurred representations barely count as successful, their very incompleteness is stamped engagingly with the determination of those inventors and scientists to realise the dream of “capturing reality”. It’s easy to forget that the birth of photography was a thoroughly scientific project, not an artistic one.

And, like many births, it was both messy and often complicated. Now, as the digital satellite speeds away from planet analogue on its journey into shallow space, even the relatively simple processes of the modern darkroom seem messy and complicated, but in photography’s first three decades merely “messy and complicated” wasn’t in it. Photographers dealt with such volatile chemicals and processes virtually demanding conjuring skills that a more accurate description would parallel Lady Caroline Lamb’s assessment of Lord Byron: “mad, bad and dangerous to know”. Regular exposure to mercury vapour, for instance, could be more fatal than playing Russian Roulette.

Initially, the budding technology may have been getting a grip on reproducing the look of the physical world but it still struggled with reproducing itself. All the first photographic processes resulted in one-off images - daguerreotypes, ambrotypes etc - until William Henry Fox Talbot invented the negative/positive process in 1840, thus opening up the medium to its distinguishing concept of reproducability. Making a negative out of an ordinary sheet of paper from which positives were later made involved a series of careful steps using various chemicals, but the first stage was to brush the sheet with a solution of sodium chloride, hence the salt reference. The resulting print exhibited a range of soft, sepia tones, slightly blurred imagery, and, with the image literally saturating the paper so that the photograph is embedded in the paper’s surface texture, there’s a palpable unity of materials that gives salt prints their unique visual identity and fascination.

Further experiments lead to simpler processes and clearer imagery, so the salt print soon became redundant and consigned to the category of “historical processes”, of academic interest only. The modernist model of history carries within it an almost genetic disposition to the notion of progress, where the simple advancement of time is wedded to increasing material improvement. This notion subtly influences our estimation of what’s significant and what’s less interesting. Thirty years ago, for instance, Ansel Adams’ work was generally held to be more important than, say, Fox Talbot’s. How could the latter’s small, grainy images of, say, brooms and bowls of fruit compete with the former’s crisp grand narratives of Yosemite National Park? This mere comparison is its own demonstration of a notion of progress. However, the relativity between these two photographers is no longer quite the case. There are many reasons for this specific shift in the estimation of Talbot’s and Adams’s work, but the reasons also apply to more general changing perceptions of photography’s connection with history, and, more specifically, with time.

Barthes’ classic definition of photography that it provides evidence of what had been is wedged between two significant assumptions. The first is on a conception of time that is linear and progressive, and secondly that making sense of “what had been” will be universally and eternally consistent. In the decades since Camera Lucida was published in 1980 both these assumptions have undergone some pretty rigorous examination. There’s calendar time - neatly linear and progressive - and there’s memory time, which ebbs and flows, and indeed alters, in relation to our recalled experience of it.

The conundrum of the “what had been” business can be exemplified by one famous example, Robert Capa’s shot Death of a Republican Soldier, Spanish Civil War, 1936. Given Capa’s “concerned photographer” status the image’s title/description was accepted automatically. It was once described by Helmut Gernsheim as the sort of dramatic picture that “firmly established reportage photography as an art form”. But, given recent debate about the photograph - was it a Republican soldier? Even, Was it staged? - the quoted phrase might be amended to read “as an artful form”.

It’s hardly a uniquely pioneering effort - because these ideas have been in the air for some time - but one of the things the McNamara Seasoned show indicated is the redundancy of the Barthes definition. We’re now living in a time after that “time”.

Ben Cauchi’s work over the past decade has, among other things, encapsulated this shift in perception, a change that has added to the richness of photography’s appreciation. Hitched to the concept of linear time, the medium was largely doomed to an assessment based merely on the apparent subject matter. Prose, not poetry. Enmeshed, however, in the ebbs and flows of memory, photography amplifies human experience rather than simply reporting events and providing that evidence of “what had been”. Cauchi’s work, on this score, can deliver very little, apart from, perhaps, provoking a shrug and the question “So what”. But once his mysterious images can be apprehended, rather, as wombs of dreams, hopes and fears their potency far exceeds the prosaic. Cauchi’s 2010 6-part portfolio, The Doppler Effect - his contribution to this show - intriguingly “commemorates” the naming of the phenomenon in 1842, contemporaneous with the invention of the salt print, declaring a synergy further illustrating the historical phenomenon of ebb and flow.

At first glance, American Dan Estabrook’s four works resemble Cauchi’s in terms of scale and subject matter, but his use of a paper support, inscriptions and pale watercolour tonings give the images a more contemporary feel as well as a more personal, “artistic” cast. Cauchi’s more solid and austere imagery retains that slight impression of artist distance characterising the medium, even when, ironically, the images may engage us more. Perhaps the most interesting part of Estabook’s involvement in the show was the inclusion of a 50-minute video from 2007 featuring him talking about his aims and processes. Published by Anthropy Arts as part of their The photographers series, this enabled illuminating insight into this photographer’s historicist approach. Inadvertently, it also highlighted the distance between Estabrook’s considered thoughtfulness and the stock jargon employed by teachers and professional associates interviewed.

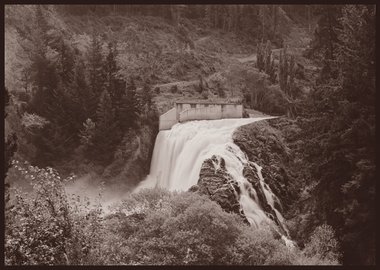

On paper, the inclusion of Wayne Barrar within this company seemed puzzling, even allowing for his dabbling with historical processes such as the cyanotype and albumen prints from as far back as the later 1990s, when Cauchi and Estabrook were barely out of shorts. But such processes have never quite masked his basically Modernist formalist aesthetic since his work first started appearing in the early 1980s. It’s simplistic to reduce his project to tracing the interactions between “nature” and “culture”, but it helps pinpoint an element in his work that’s often unremarked on. For all its formalist look it’s predicated on the notion of the Sublime, a phenomenon reaching its height in the later 18th century, a combination of decline in religious belief (the worship being transferred to Nature), and a slow dawning that humankind, not a deity, was responsible for what happened on the planet - the origins, indeed of the environmental movement.

The Sublime is inextricably part of the Romantic movement, and as such was held at arm’s length by Modernism. All that declaring in front of waterfalls was just too woozily emotional for the 20th century’s stern proponents of intellectual rigour and truth to materials. In photography you were allowed some Ansel Adams grandeur, but no early Steichen misty pools or Horsley Hinton cloudy skies. The spectre of Pictorialism haunted serious photographers throughout the entire reign of Modernism. As further evidence of history’s forgiving ebb and flow, a photographer like Barrar is now freer to, as it were, come out and reveal more of his Sublime side. And this was the most surprising element of the exhibition Seasoned: contemporary salt prints. Not just surprising either. Satisfying too in the way it so unexpectedly deepened appreciation of not only this work but Barrar’s whole oeuvre, and admiration for his continuing grip on pressing issues having currency way beyond the walls of galleries and the self-referential chatter of the art world.

Back in the 1970s we all believed that oil would be what determined future major moves in the global political chess-game. Now we know it’s going to be water: sea water for the climate, fresh water for us. Barrar’s depiction of water in these salt prints does indeed flirt with photography’s Pictorialist history, but our knowing what the stakes are allows the images to shy away from nature worship to nature alert. Oscar Wilde once observed that you would have to have a heart of stone not to laugh at the death of Little Nell. Similarly, you’d need a heart of stone not to find these Barrar images unfashionably beautiful, despite their chilling moral implications.

Seasoned brought together three practising photographers each of whose work not only provided examples of a fresh interest in both photography’s own history and what were thought of as historical processes, but also, collectively, demonstrated powerfully the inadequacy of the linear historical model - a matter of some importance for the medium of photography and its interpretation. The small settlement of Upokongaro lies about 13 kilometres upstream from the mouth of the mighty Whanganui River. In the regularity of nature’s ebbs and flows salt has been detected in the water at Upokongaro.

Peter Ireland

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.