John Hurrell – 1 August, 2023

Shepherd likes to take a symbol and, in his imagination, treat its form with a new material that alters its meaning—by semantically reinforcing, or flipping or twisting it, or rubbing it up against something unexpected. He uses that envisaged retextured or reshaped form as a basis for a painted image that provides a tangential comment on the original symbol, or the newly constructed title. Or a simple surreal presence perhaps beyond language. Each image is jammed full of interpretive possibilities.

With this new Michael Shepherd exhibition, we find in the large Two Rooms downstairs gallery, three paintings on board, and ten on paper, ‘still lifes’ placed in landscapes; rendered symbolic objects or plants that are rife with political and poetic overtones. These might be seen (via the very considered rendering) as similes or metaphors—although I think the tighter and more specific ‘symbol’ is probably the most apt term for the whole group. The austere, often symmetrical (occasionally foggy) works are the result of a residency Shepherd had in Henderson House in Alexandra, Central Otago, two years ago.

It is inevitable that, because of the location, Shepherd‘s paintings might at times be compared with those of Grahame Sydney, though Shepherd uses landscape as a kind of versatile theatre stage, a weather-conscious horizontal backdrop on which he places items of symbolic interest—while Sydney is curious about background vistas, the material particulars of manmade structures, and sharp definition. Also, Sydney tends to be planar, while Shepherd in this show at least, is more linear. While both are highly tactile, Shepherd is more vehemently unconventional and strange, tending at times to be piercingly fetishistic. We have two, very different, sensibilities.

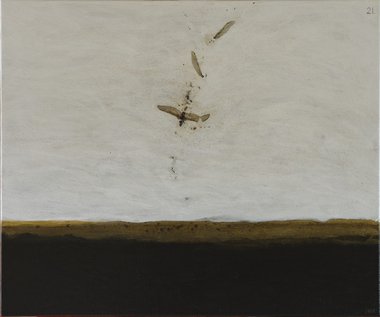

Of the Shepherd selection, three are notably different from the rest of the images, and vaguely link to the sixteen Denis O’Connor wall works upstairs. One is a ‘collage’ that uses varnished scattered insect body parts from a large crushed dragon fly to indicate an exploding biplane. Its title, 1914, transmutes the Otago setting to that of Flanders. Two others indicate Shepherd’s well-known interest in botany. Both The Lauds in Lauder (a vase of ‘weeds’) and Res Publica (a fasces bundle) wittily incorporate dried reed and grass stems in their images and allude to imported colonial vegetation and the Commonwealth.

Many of the other paintings seem to overtly reference Catholic Rome (See) or Anglican England (Orb), an amusing twist for ecclesiastic objects now reset through art in Presbyterian Otago.

Shepherd likes to take a symbol and, in his imagination, treat its form with a new material that alters its meaning—by semantically reinforcing, or flipping or twisting it, or rubbing it up against something unexpected. He uses that envisaged retextured or reshaped form as a basis for a painted image that provides a tangential comment on the original symbol, or the newly constructed title. Or a simple surreal presence perhaps beyond language. Each image is jammed full of interpretive possibilities.

Sometimes he’ll take a mythological (Apollo and Daphne) or religious /political narrative (Three Thickets, a crown made of matagouri), zero in on a botanical reference point and find a local equivalent. Or create a vertical heraldic-like cluster—quoting established symbols—on a stake / bottle that is about to be burnt (Corsage for a Cortège) to make a point about the relationship of the English monarchy to the constitution of Aotearoa.

This greatly nuanced show (rich in its ecological and historical underpinnings) is accompanied by a superbly helpful (hand-out) essay by Peter Simpson that is dense with intriguing information about Shepherd’s working methods and thinking patterns.

It is a quiet, dignified yet rewarding, layered exhibition that is deceptively unassuming—but with its admirable slipperiness is nevertheless compelling.

John Hurrell

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects

Two Rooms presents a program of residencies and projects Advertising in this column

Advertising in this column

This Discussion has 0 comments.

Comment

Participate

Register to Participate.

Sign in

Sign in to an existing account.